Oswald Padonou

Burkina Faso’s parliamentarians may have unanimously adopted the law allowing for the recruitment of Volunteers for the Defense of the Fatherland (VDP) on Thursday, January 23, 2020, but it is unlikely that the Civilian Volunteer Corps that will be created and trained in 14 days will be able to change the security situation and restore peace in the Country of Honest Men.

As the country has been experiencing an increase in criminal activities by terrorist armed groups (GAT) since 2016, the solutions devised and implemented to mobilize troops have moved from the denial of the threat to an increase in self-defense groups. The so-called Koglweogo, “forest guards” in Mooré language, have consolidated themselves from the determination to counter this “institutionalized insecurity” and have flourished in a context of weak territorial coverage and structural incapacity of the defense and security forces.

These alternatives designed on the periphery of the State and its institutions invariably lead to the same result: increasing insecurity, thousands of deaths and casualties, confused refugees and displaced persons, a distressed population, and an overstretched and exhausted army. In this context, VDPs are more a political response to the demand and the need for a change of direction in the face of a general lack of action by governments, a feeling shared by a significant part of the population.

The so-called Koglweogo, “forest guards” in Mooré language, have consolidated themselves from the determination to counter this “institutionalized insecurity” and have flourished in a context of weak territorial coverage and structural incapacity of the defense and security forces

Except that logically, where defense and security forces are struggling to deal with the steamroller of jihadists and other criminal gangs, civilian volunteers cannot make the difference. Also, at an operational level, detrimental rivalries cannot be ruled out, with Koglweogos benefiting not only from a certain presence, especially in rural areas, but also from varying degrees of legitimacy.

The only “advantage” of the model adopted by Burkina Faso seems to be the financial cost of the initiative, which is quite controlled, since these Volunteers will not be paid during the period of implementation of the contract with the State. Apart from training and equipment costs, the law provides only for their demobilization allowances and financial assistance to their families in case of death in discharging their responsibilities.

These alternatives designed on the periphery of the State and its institutions invariably lead to the same result: increasing insecurity, thousands of deaths and casualties, confused refugees and displaced persons, a distressed population, and an overstretched and exhausted army

Yet models of security auxiliaries in other countries have proved their worth and could have inspired Burkina Faso’s government and legislators. For instance, Senegal is successfully experimenting with community security with 10,000 unarmed young people, recruited in their communities, remunerated, cared for and supported in their post-employment integration projects, and who are reliable relays of the public security service and valuable assets for the national police and gendarmerie.

Along with this dual-purpose model of civic service, community security services and improvement of youth employability, other experiences of operational reserve have also proven successful elsewhere and should be explored and adapted to the current challenges in the Sahel, since the responses to the challenges must be mainly structural.

It is therefore time for West African countries to consider equipping themselves with operational reserves and restoring military service, which are certainly more expensive, but much more effective in containing the threat and preventing the collapse of the State. Egypt, the continent’s leading military power, already has such reserves, as do Algeria, Morocco, and South Africa.

Senegal is successfully experimenting with community security with 10,000 unarmed young people, recruited in their communities, remunerated, cared for and supported in their post-employment integration projects

Even France, which is a model for some of these countries, has such reserves and created a National Guard, which, unlike Mali, Niger and Benin, the latter of which will soon have them under the new status of the armed forces currently under consideration by Parliament, is made up exclusively of defense and internal security reservists who provide regular and supervised support to the armed and public security forces and, as the situation may require, directly to the population.

There are many advantages to the Operational Reserve. It is generally composed of young volunteers, former active soldiers, or career soldiers. In some countries where conscription is still used, a distinction is made between active military duty and reserve duty, with periods of youth passage into the armed forces and regular periods of integration of reservists into the regular army.

Reservists therefore receive the same level of training as active soldiers in the areas of their employment and can be mobilized at short notice for military and police operations, including external operations, such as those currently taking place in the Sahel. Reserve is therefore a pool of troops and skills and is an essential part of the Army-Nation link, as is the case in Germany.

It is therefore time for West African countries to consider equipping themselves with operational reserves and restoring military service, which are certainly more expensive, but much more effective in containing the threat and preventing the collapse of the State

In North America, Reserves are an integral and important part of the armed forces. In the United States, they represent 39% of the total armed forces while Canada has almost as many operational reservists as active members of the army.

So why reinvent the wheel? Why, in Burkina Faso and in other sub-Saharan African States, should we not learn from successful experiences elsewhere and adapt them to the local context and the available resources, instead of continuing to develop pseudo-response capacities on the periphery of institutions, away from national forces and in perpetuation of informal logics that are causing so much harm to our societies? Why?

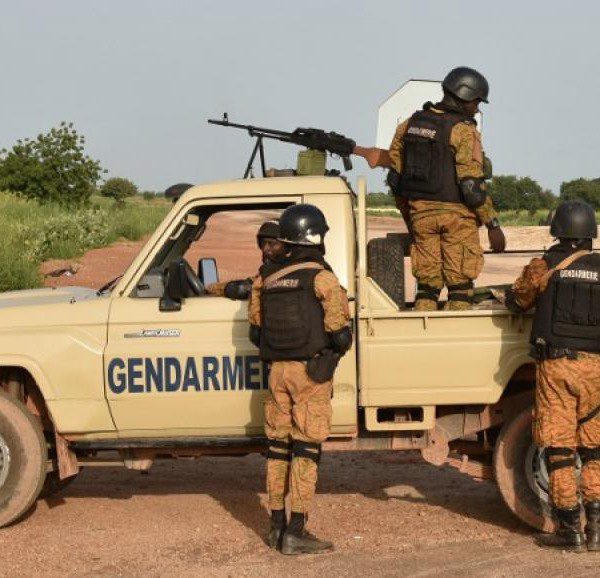

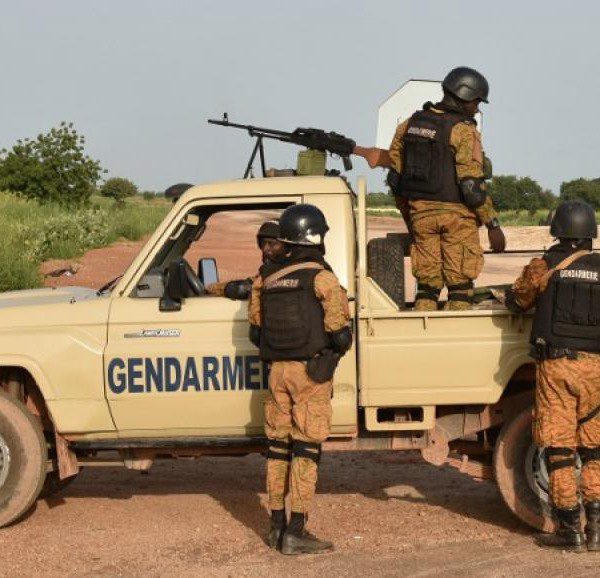

Crédit photo : PressAfrik

A Doctor in Political Science and President of the Beninese Association for Strategic and Security Studies (ABESS), Oswald Padonou is a Research Professor in International Relations, Strategic Studies, Defense and Security Policy. He is a specialist on West Africa and is the author of several publications on the political and security dynamics of the region.