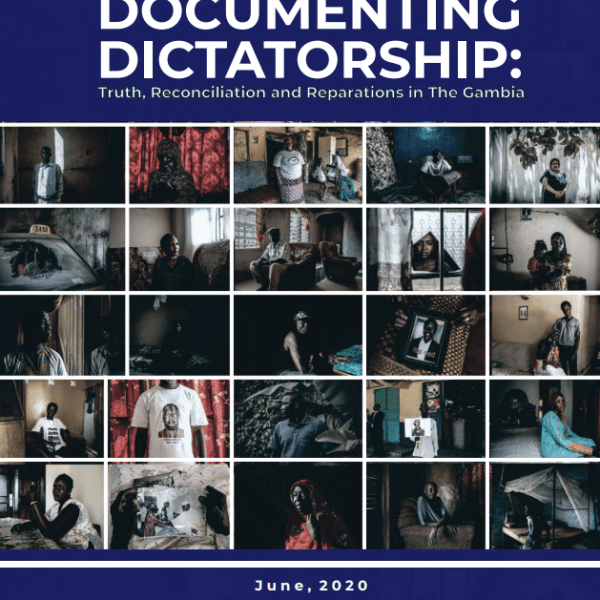

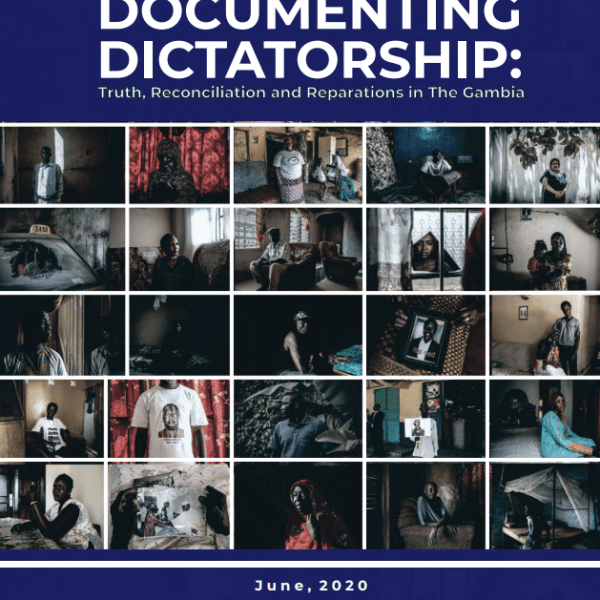

Authors: Idayat Hassan and Jamie Hitchen

The Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) is an independent, not-for-profit, research, training, advocacy and capacity building organization. It was established, in the United Kingdom in 1997 and subsequently registered in Nigeria in 1999, to mobilize global opinion and resources for democratic development and provide an independent space to reflect critically on the challenges posed to the democratization and development processes in West Africa. CDD also provides alternatives and best practices to the sustenance of democracy and development in the region.

Date of publication: June 2020

Organisation’s site: CDD

Les élections de décembre 2016 ont marqué un tournant décisif pour les Gambiens qui voulaient en finir avec le régime de Yahya Jammeh. 22 années passées sous un régime marqué par des violations des droits de l’homme telles que des disparitions forcées, des arrestations et des assassinats illégaux, en passant par la torture, la violence sexuelle et sexiste et la persécution d’opposants politiques réels ou supposés. Selon une étude d’Afrobaromètre réalisée en 2018, 28% de Gambiens ont déclaré qu’eux-mêmes ou un membre de leur famille avaient subi une forme de violation des droits de l’homme pendant la présidence Jammeh. Yahya Jammeh, qui avait pris le pourvoir en Gambie, suite à un coup d’État militaire en juillet 1994, comptait briguer une cinquième mandature en 2016, mais il a été battu par le candidat de l’oppositon Adama Barrow. Ce dernier a promis, lors de la campagne présidentielle et même après son élection, la création d’une commission, chargée d’enquêter et d’établir un dossier historique impartial sur la nature, les causes et l’étendue des violations et des abus des droits de l’homme commis entre juillet 1994 et janvier 2017. Cette commission pourrait procéder à l’octroi de réparations aux victimes. C’est dans ce contexte qu’a été créée la Commission de vérité, de réconciliation et de réparation de la Gambie (TRRC). Depuis janvier 2019, la Commission a recueilli 220 témoignages publics, dont 40 d’auteurs présumés, et 462 autres déclarations des victimes et des auteurs. WATHI a choisi ce document parce qu’il fait un état des lieux des actions de la Commission de vérité, de réconciliation et de réparation depuis sa mise en place. Cette Commission a pour rôle de dénoncer les faits de violation des droits de l’homme, de sensibiliser sur la question et elle ne peut en aucun cas traduire en justice ni juger les auteurs impliqués dans ces affaires. En cela, elle est confrontée à plusieurs difficultés qui jettent un discrédit sur son impartialité, sa neutralité, du fait de certains acteurs politiques et de fortes réalités ethniques. Why did we choose this document ? The December 2016 elections marked a decisive turning point for Gambians who wanted to put an end to Yahya Jammeh’s regime. 22 years under a regime marked by human rights violations ranging from enforced disappearances, torture, sexual and gender-based violence and persecution of real or perceived political opponents to unlawful arrests and killings. According to an Afrobarometer survey conducted in 2018, 28% of Gambians said that they or a member of their family had suffered some form of human rights violation during the period of Jammeh’s regime. Yahya Jammeh, who had taken control of the Gambia following a military coup in July 1994, had intended to run for a fifth term in 2016, but unfortunately was defeated by Adama Barrow. During the presidential campaigns and after his election, Adama Barrow promised to establish a commission to investigate and establish an impartial historical record of the nature, causes and extent of human rights violations and abuses committed between July 1994 and January 2017 and to consider reparations for victims. It is within this context that the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparation Commission of the Gambia (TRRC) was established. Since January 2019, the Commission has collected 220 public testimonies, including 40 from alleged perpetrators, and a further 462 victims’ and perpetrators’ declarations. WATHI chose this document because it provides an overview of the work of the Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparation Commission since its establishment. This Commission, whose role is to denounce, raise awareness and which can in no way bring to justice or judge the perpetrators of human rights violations, faces several difficulties that discredit its impartiality and neutrality, due to certain political actors and strong ethnic realities.

Sept recommandations majeures ressortent de ce document et pourraient servir à tout pays confronté aux violations de droits de l’homme et inscrit dans un processus de transition d’une justice équitable et de réparations des dommages après des années de dictature. What lessons for the countries of the WATHI zone ? Seven major recommendations result from this document and could be of use to any country facing human rights violations as part of a process of transition to equitable justice and reparation of damages after years of dictatorship.

Extracts from the document, pages: 6-7; 9-15; 18-19; 22-25; 27-28

Towards a New Gambia

Yahya Jammeh, aged just 29, took control of The Gambia in a military coup in July 1994. He sought popular validation for his rule by holding, and winning, elections in 1996, 2001, 2006, and 2011. Each time securing more than 50% of the vote in polls that were described as “tainted” and “lacking legitimacy” by election observers. But in December 2016, seeking a fifth popular mandate, Jammeh could only muster 39.6% of the vote and was defeated by the candidate of a coalition of opposition parties, Adama Barrow.

Having initially appeared to be willing to accept the results, Jammeh then changed his mind citing ‘abnormalities’ and called for the results to be cancelled and fresh elections held. But after over a month of protracted negotiations with leaders from the Economic Community of West African States, and with the threat of regional military action looming, Jammeh left The Gambia for exile in Equatorial Guinea on 21 January 2017. During Jammeh’s 22-year rule, human rights violations ranging from enforced disappearances, unlawful arrests and killings, torture, sexual and gender-based violence, and persecution of real or perceived political opponents, characterised The Gambia.

A 2015 Human Rights Watch investigative report detailed how security services and guerrilla groups routinely used intimidation, violence, arson, and forced disappearances against people who spoke out against those in power. For journalist Mustapha Darboe, “Jammeh was the Gambia, and the Gambia was Jammeh: facts were what he said”. 28% of Gambians reported that they or a member of their family had suffered one form of human rights violations in the period of Jammeh’s rule, when surveyed by Afrobarometer in 2018. These violations, as well as the regular dismissal of senior government officials, had a direct effect on state effectiveness; eroding the capacity of the government to deliver basic services.

But the ‘new Gambia’ promised by President Barrow and his allies – who were unable to maintain the coalition’s unity once in office – has found it difficult to fully throw off the trappings of the old. That is not to say that The Gambia has not changed significantly. The ability to convene and speak freely – an unimaginable reality under Jammeh – is now a feature of daily life Gambians can enjoy, but reforms to the system of how things work have proved more difficult. Barrow’s government has struggled to disentangle the state from its authoritarian past. Economic challenges, such as unemployment, remain acute.

A protest in January 2020 against Barrow for not adhering to his coalition promise to serve just three years of his constitutionally mandated five-year term turned violent. 137 protestors were arrested, among them prominent journalists. Two radio stations – Home Digital FM and King FM – were also temporarily shut down, accused of “allowing their media to be used as platforms for inciting violence”. All the protestors were eventually released, and the radio licenses restored, but the government took the opportunity to ban the ‘Three Years Jotna’ movement, calling it “subversive, violent and illegal”. The response of the state to this and other recent protests has raised concerns as to how much has really changed beneath the surface in the ‘new Gambia’.

If we prosecute people, but we don’t address the systematic cultural causes of the dictatorship, we are likely to slide back into dictatorship at some point

Even though a multitude of reforms and transitional processes are ongoing questions remain as to whether the government is doing enough when it comes to transparency and accountability. An anti-corruption commission is set to be established in 2020, but the chair will be appointed directly by the President, raising the spectre that it will not be sufficiently independent.

Concerns have also emerged about the government’s willingness to fully enact the new basic law proposed by the Constitutional Review Commission (CRC); with Barrow rumoured to be keen to adjust a two-term-limit clause so that it would only apply from 2021. The current provision would count a victory in the 2021 election as Barrow’s second, and final, term in office. The document will be put a public vote after it undergoes scrutiny in the National Assembly.

In the view of one direct victim of the Jammeh regime, “this is not the new Gambia, we haven’t yet seen a change to the system of government”. Prominent commentator and activist Madi Jobarteh agrees, “there are a lot of abuse of resources, abuse of power…that’s a huge frustration and, practically, people have not seen any tangible socio-economic change in their lives”. It is in this context that the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) operates.

Creating the commission

A truth commission was promised to Gambians during the 2016 presidential campaign trail by Barrow and the coalition of opposition political parties backing him. After taking office, time was spent reviewing and learning from experiences of other countries on the continent. The Ministry of Justice (MoJ) visited both South Africa and Sierra Leone in 2017 to learn from their experiences of using transitional justice to respond to apartheid and civil conflict, respectively.

The Gambia’s experience was not one of conflict, but the duration and hidden nature of abuses had created many victims who wanted truth and, ultimately, justice. For Dr. Baba Galleh Jallow, the Executive Secretary of the TRRC, there was a more hidden, but equally important reason for its creation, “there are certain systemic and cultural factors that enabled the dictatorship that needs to be brought out into the open and discussed… If we prosecute people, but we don’t address the systematic cultural causes of the dictatorship, we are likely to slide back into dictatorship at some point”.

The Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Act of 2017, assented to by the president on 13 January 2018, provides for “the establishment of a Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission; to investigate and establish an impartial historical record of the nature, causes and extent of the violations and abuses of human rights committed during the period July 1994 to January 2017 and to consider the granting of reparations to victims 19 for connected matters”.

Since the first public hearing was held on 7 January 2019, the Commission has collected 220 public testimonies from witnesses, including 40 from alleged perpetrators. A further 462 statements were collected in 2019, from both victims and perpetrators, during outreach activities 20 according to the TRRC’s interim report. Among the Commission’s objectives, as laid out in the Act, are “to promote healing and reconciliation… to provide victims an opportunity to relate their own accounts of the violations and abuses suffered… and to prevent a repeat of the violations and abuses suffered by making recommendations for the establishment of appropriate preventive mechanisms including institutional and legal reforms”. Justice is not part of the Commission’s mandate.

However, it will be able to recommend prosecution for those who bear the greatest responsibility in its report findings. It remains for the Ministry of Justice and others in the government to decide how to act, meaning that there is no guaranteed amnesty for perpetrators who testify before the Commission. The 11 commissioners of the TRRC – headed by its Chair, Lamin Sise – were appointed by the president after a rigorous, and public, selection process designed to represent The Gambia’s ethnic and regional make-up.

The Commission is supported in investigations and guiding witnesses through their testimony by a Lead Counsel, Essa Faal, and Investigations Unit. Faal was appointed directly by the Attorney General and Minister of Justice in September 2018 even though there is no provision for such a role in the Act. This has led legal experts to suggest that, in this regard, at least, “how it [TRRC] was conceived and how it works in practice is quite different”. But for Dr. Ismaila Cessay, a lecturer at the University of the Gambia, the main challenge facing the Commission has stemmed from a lack of a grassroots national dialogue about what the TRRC would look like, and try to achieve, prior to its creation.

An issue that continues to have an impact on how it functions, “it would have helped to establish better what Gambians wanted from a transitional justice process, what justice looked like, how reconciliation could and should happen….as it was there was limited public debate on the transitional justice mechanisms to be used in The Gambia, it was imposed from the top-down”.

The TRRC did hold some pre-commission consultations across the country in August 2017 where Gambians views were solicited on a wide range of issues. But the role played by development partners and donors in driving and funding the process was key in shaping the way forward. In the view of a prominent legal practitioner, “Gambia’s TRRC was donor driven, not driven through in-depth national consultations, and this has created confusion as to its objectives among different people”. Sait Matty Jaw, a lecturer at the University of The Gambia agrees that donors provided the resources but insists that the policy directive has always been driven by Gambians. His concern surrounds the lack of in-depth public consultations about the TRRC, “they were more about seeking citizen approval for what they wanted to do, rather than asking Gambians to help shape and design the process”

Key Findings, matching expectations?

Before the TRRC process, many simply knew only that they had gone out never to return. An Afrobarometer survey conducted before the start of the Commission found that 30% of Gambians saw “an accurate record of human rights abuses by the past regime” as one of its two most important outcomes. Efforts have been put in place to ensure that the narratives relayed by the 220 witnesses who have appeared at the TRRC so far have reached as wide an audience as possible.

But the TRRC’s work is more than just public testimony. Discussions and truth-telling are also happening away from the cameras in ways that can support community level efforts to establish truth led by its community outreach activities and supported by civil society organisations and victim support groups. The Gambia Transitional Justice Working Group, a civil society-led consortium, was established in 2018 to coordinate the activities of non-state actors supporting the TRRCs work.

For victims, simply knowing the truth about what happened to a loved one or family member, can be an important part of the healing and grieving process

The TRRC is offering a platform through which people can tell their stories and be validated for what they experienced utilising a victim centred approach. But the decision not to conduct a formal nationwide statement taking exercise will limit the Commission’s ability to integrate the stories of victims with other Gambians. Nonetheless, public hearings are broadcast live on television networks and streamed through Facebook and YouTube channels, with as many as 6,000 viewers tuning in to watch testimonies relating to some of the most notorious abuses or controversial issues.

“In many cases, more than one person will be watching the same screen, so the number is likely higher,” says Essa Jallow, Head of the Communications Unit at the TRRC. To further widen the reach, content is being translated into The Gambia’s two main languages – Wolof and Mandinka. Although a lack of resources prevents this being done live, it still offers a valuable resource that is available to Gambians now, and in the future, to hear the testimonies in the language they understand best.

A group of market traders who took part in a focus group discussion for this study relayed how they listened to the proceedings live on radio, with some even watching edited highlights on the television in the evenings. “When there is a key witness at the TRRC, everyone will be talking about it – online and offline,” noted one trader. Radio remains a key source of information for Gambians, but in some instances, the unofficial translations undertaken by the programme hosts, to facilitate local language discussions in phone-in shows, can hinder as much as help.

Mistranslations and the framing of a debate to highlight segments to fit a certain narrative, can have “implications for how and what people are hearing about what is happening at the TRRC”. Efforts to improve the media’s coverage of transitional justice processes in The Gambia through training and workshops are ongoing and have been supported by the Commission, in partnership with the Ministry of Justice and development partners.

Social media too is allowing for hearings to reach and engage with a wide audience, and for details that emerge to be debated and discussed. 16% of Gambians are active social media users according to 2020 data from We Are Social but WhatsApp messages can penetrate offline and influence wider discussions. The TRRC recognises the critical role it can play in setting the agenda and its Communications Unit included visits to key diaspora communities, active online but living outside of The Gambia, to encourage constructive online engagement.

The TRRC’s executive secretary noted that “we had a desire to make the TRRC process as open and transparent as possible from the beginning and social media has certainly played a role in helping us to do this”. The importance of engaging with an online audience was also highlighted by a civil society activist who agreed that “social media cannot be left behind in the search for truth in the Gambia,” but who felt it “needs to be better regulated to stop online abuses”.

Supporters of, and those allied to, the Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC) – the former ruling party – are widely accused of spreading false information online that aims to discredit witness testimony and the work of the TRRC. This has included persistent accusations, denied by the Commission, that witnesses, and even perpetrators, were being paid by the TRRC to relay particular narratives at the hearings. Dodou Jah, deputy spokesperson and secretary of the APRC, musing about the testimonies offered by the Junglers asked, “did they do it because it was the truth? Or did they do it knowing that if they told that truth they would be released [for now] from prison”. He claims he knows of people being paid D50,000 ($1,000) to give a certain testimony at the TRRC but produced no evidence to support this claim. These are the sorts of rumours and stories that circulate widely and frequently online during live testimony.

APRC supporters have consistently accused the TRRC of being a “witch-hunt” against Jammeh and his supporters given the time period it is mandated to focus on. They have also questioned how impartial the commission can be when it is composed of those who they see as having a grudge against the Jammeh regime. Jah argues that “there are stories [ones with political ramifications for those still in office] that are not being touched by the TRRC”. Whilst many Gambians accuse the APRC of being in denial about what happened under Jammeh and how much control he directly exercised over those beneath him, there is a general tendency for social media debates and discussions about individual testimonies to be heavily influenced by party political viewpoints.

For some, the way in which social media has increasingly individualised the TRRC has made it more a personality contest than a quest for the truth

In testimony given to the Commission in October 2019, Bintou Nyabally – a supporter of the long-time opposition United Democratic Party (UDP) – claimed that when soldiers entered UDP leader, Ousainou Darboe’s compound in 2015, Adama Barrow was among those who hid inside, leaving women to trade insults with soldiers. Given Barrow’s subsequent falling out with Darboe – his 2016 election ally, and later vice-President – the president’s supporters took to social media to accuse Nyabally of lying to the Commission in order to tarnish Barrow’s reputation. On the flip side, UDP supporters used her testimony to push online the image of Barrow as weak and not at the forefront of the effort to resist the Jammeh regime. An example of the way individuals’ truths, given as testimony to the TRRC, are interpreted on social media, often as it is ongoing, through a political lens.

For some, the way in which social media has increasingly individualised the TRRC has made it more a personality contest than a quest for the truth. This reality has also shaped the approach of Lead Counsel Essa Faal, in the view of one respondent, “Faal wants to be seen as having ‘won’ his duel with a perpetrator…a lot of discussion online is about who is winning the big personality clashes as TRRC”.

Perpetrators on trial

The 2018 Afrobarometer survey found that 68% of Gambians wanted the perpetrators of crimes and human-rights abuses during Jammeh’s regime to be tried in court, irrespective of the work of the TRRC; 28% saw the prosecution and punishment of persons found guilty of crimes against humanity as one of the two most important outcomes of the TRRC’s work. As one individual, who had close family members that were disappeared by the former regime said, “the key thing for me, as a victim, is justice. I would want Jammeh to come back and stand trial for what he did”.

The TRRC is not mandated to try and convict individuals for crimes they admit to but remains able to indict them for the human rights abuses they participated in at the conclusion of the two-year process in its recommendations. However, the testimony provided by members of the ‘Junglers’ in July 2019 raised questions about consequences for previous actions.

Testimony given by ‘Junglers’ Omar Jallow, Amadou Badgie, Malick Jatta and Pa Ousamn Sanneh, in which they admitted to direct involvement in the killings of dozens of Ghanaian migrants; the murder of journalist Deyda Hydara, a former president of the Gambia Press Union and a critical voice of the regime who was shot in 2004; and shed new light on the killing of country’s former spy chief Daba Marenah, former military chief Colonel Ndure Cham, former lawmaker Ma Hawa Cham and dozens of others who had disappeared under mysterious circumstances during the dictatorship, gripped the nation. But their subsequent release from prison, without charges being levelled against them, was met with confusion and anger.

As Essa Jallow of the commissioned explained, “the TRRC does not have the power to release individuals, that is a decision made by the Ministry of Justice, but many people understood that the commission had directed for the Junglers to be released after they gave their testimonies, this was not the case”. The decision to release the ‘Junglers’, who had been held without charge, and therefore unlawfully, according to Justice Minister Abubacarr Tambadou, for almost two years, came as a surprise to the TRRC, as it did the general public.

The MoJ’s decision was met by public opposition, as many saw the release of the Junglers, so soon after their testimony, as setting them free and not in keeping with the TRRC’s promise of a victim-led process. Particularly given the lack of consultation with the TRRC or victim support groups prior to their release. “A lot of Gambians lost hope about the prospects for justice when the Junglers were released as it created a sense that people can say anything in their testimonies and then walk free” was a view shared by a focus group respondent that captured the sentiments of many.

The key thing for me, as a victim, is justice. I would want Jammeh to come back and stand trial for what he did

“People expect a lot from the TRRC, but not all of it, the TRRC is mandated to deliver,” says communications head, Jallow. There is an ongoing challenge of explaining its mandate to ordinary Gambians, “sometimes when we engage with journalists we try and make broader points about the functions of the commission and its mandate, but journalists want our take on specific testimonies, there is rarely space for us to explain the more day-to-day work we do to Gambians through public platforms”. But he acknowledged that “for victims this is a lengthy process and they are eager for justice and reparations; they want it now, not in a couple of years”.

Truth on its own is not enough for Ebrima Jammeh, whose father was killed by the Junglers, “I can never forgive what they did. I want to see the released Junglers behind bars. I cannot accept someone who killed my dad walking free”.

Compensation concerns

The Liberia Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommended that a form of both individual and community reparation was desirable to promote justice and genuine reconciliation. But the implementation of this recommendation has been a major challenge. Sierra Leone’s truth and reconciliation process had a reparations programme, but it was largely seen as a failure. “It was not set up in a timely or efficient way, and reasonable reparations have not been paid to those most severely affected by the war”. Even though reparations were arguably the aspect of the transitional justice programme that were most important to a majority of Sierra Leoneans.

In the 2018 Afrobarometer study, five types of reparations were mentioned when asking individuals about their two main expectations for the TRRC. When taken together, 43% of respondents believed some form of reparations was a key outcome of the work of the Commission. Regulations to guide the reparations process have been discussed with leading international experts. They are now undergoing a review process and should be in place in the first half of 2020.

It must also ensure that sufficient funding is forthcoming for the many victims. Otherwise, there is a danger that reparations will not be commensurate with the suffering endured. So far, reparations have taken place on an ad-hoc and interim basis using a portion of the Ds50 million (US$ 1 million) paid by the government into the Victims Support Fund of the TRRC in October 2019.

Minister of Justice, Abubacarr Tambadou, hinted that more funds could be made available as more of Jammeh’s assets were sold, though he cautioned that the process might take time. That initial deposit was raised from selling some of Jammeh’s assets in line with the findings of the Janneh Commission – an inquiry set up by the current administration to probe into the financial dealings of Yahya Jammeh, and his close associates, from July 1994 to January 2017.

The September 2019 report of the Janneh Commission established that Jammeh owned 281 properties in the country, as well as assets abroad and found that disproportionate amounts of resources were wasted, misappropriated and diverted amounting to over Ds1 billion and US$300 million. However, the government has been criticised for its selective implementation of the Commission’s recommendations.

Key individuals in the current administration who had also been a part of the previous regime – most notably Finance Minister Mambury Njie and Chief Protocol Officer Alhagie Ousman Ceesay – were absolved of responsibility in the government white paper that pushed back against the Commission’s findings. “The government has failed in its responsibility in acting appropriately on the recommendations of the Janneh Commission in good faith” was one view shared by many.

Interim reparations have filled the gap whilst the regulations are developed and finalised. This has included paying school fees to support children of victims, healthcare for those who have medical conditions brought about by torture and even a few grants issued to support small businesses that were decimated by Jammeh. Four victims, who were shot during a protest in April 2000 and still live with health complications, were partially sponsored by the TRRC to receive treatment in Turkey in late 2019. The TRRC also provides ongoing psycho-social support to victims as part of its work through a dedicated unit.

There have even been ad-hoc cases of ordinary Gambians crowdfunding support to victims following their testimonies, to allow them to seek medical attention for ailments suffered as a result of abuse and torture at the hands of the Jammeh regime. The interim TRRC report notes that as part of its diaspora engagement over $25,000 was raised and contributed to the Victims Support Fund from Gambians in Sweden, Norway, the United Kingdom and the United States.

But the forthcoming, and more comprehensive, formal reparations scheme is needed to ensure an equitable distribution of funds in a way that is seen as fair by victims. The Gambia Center for Victims of Human Rights Violations, an advocacy group set up in 2017 to represent the collective voice of victims, is compiling a register, to be forwarded to the TRRC, as well as supporting the Commission’s efforts to take victim statements across the country, in the hope that “they [victims] will benefit from the reparations made available” .

With two representatives in each of The Gambia’s regions they are also involved in supporting citizen awareness of the work of the Commission and in working to provide counselling and psycho-social support to victims and their families. Center staff are concerned about the need to manage victims’ expectations believing that many victims have chosen to come forward to give public or private testimonies not just to tell their side of the story but expecting some form of compensation.

At the end of 2019, the TRRC’s Victim Support Unit had registered 941 victims of human rights abuses

The TRRC will need to produce clear and transparent guidelines as to how claims would be made and processed if they want to avoid accusations of exclusion and bias. “It is still not clear how reparations are going to be given out and how those costs will be fully met. So far Ds50 million has been set aside for reparations but it is not clear how that will be allocated and how they will judge the level that you have been affected: will it cover medical or education fees or returning of land or money for lost income?” noted one civil society representative.

Answers to these questions should be clearer when the TRRC releases its guidelines but communicating these messages to all Gambians and ensuring those who want to make claims are able to do so, will be critical. So too will be ensuring that transparency is to the fore in the issuance of payments to avoid accusations that the commission is showing favour to individuals and to ensure that there is accountability.

The TRRC will also need to communicate how reparations will be provided once its mandate expires given that it is unlikely the process can be completed before then. In November 2019 the Attorney General mentioned that the newly established National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) will take over the legacies of the TRRC, “so this may mean the NHRC will oversee reparations” notes Sait Matty Jaw, a lecturer at the University of The Gambia, “but like many things with the legacy of the TRRC things aren’t clear…what is clear is that when the commission is dissolved, it won’t be in existence”.

According to one legal expert familiar with the work of the Commission, “the funding issue coupled with the complexity of awarding reparations means that there has to be a mechanism for the TRRC’s reparations framework to be implemented even after the Commission completes its mandate”. In their view, “the modalities of how to do that would likely be part of the Commission’s recommendations in its final report.”

(Re)Building The Gambia

34% of Gambians expect national peace, reconciliation, forgiveness and healing to be one of the major outcomes of the work of the TRRC. Promoting healing and reconciliation is one of the core objectives of the Commission, but, at the national level, this has proved to be quite difficult in practice, in part because of the fast-changing political landscape in which the TRRC operates.

The coalition which defeated Jammeh, and which supported the transitional justice project, lasted only a few months before political infighting and a lack of a common enemy, broke it apart, though it held together formally much longer. In January 2020, Barrow launched his National People’s Party (NPP), under whose banner he will contest the 2021 elections, marking a formal split with the UDP, the leading opposition party during the Jammeh era and the holder of 31 of the 58 seats in the current National Assembly. But this was a confirmation of reality, especially after Barrow dismissed long-time UDP leader, Ousainou Darboe, from his position of vice-president in March 2019. This political split, combined with the fact that Barrow has brought back, or retained, some key officials who served under Jammeh has further complicated the work of the TRRC.

Political parties in The Gambia could do more publicly to show their support and commitment to the process, beyond simply saying that they support its work and will let it run its course

One victim felt that the president specifically “needs to do more to make Gambians feel like he is supporting the process, rather than using it for political gains”. The decision of the government to grant a permit to the APRC to rally in support of Jammeh’s return in January 2020 was seen as an insult by many victims. This followed on from remarks Barrow made in December 2019, when visiting Jammeh’s home region of Foni, that the former president could be allowed to return to The Gambia, but only if he agreed to live as a private citizen. That prospect was quickly dismissed by the Minister of Justice, but not before it caused uproar among victims, particularly those fearful of what such a return would mean for their own safety and the ability of the TRRC to continue to do its work.

Efforts to interfere, albeit indirectly, in the TRRC process have also been attempted by leading figures in other political parties. People’s Democratic Organisation for Independence and Socialism leader, Halifa Sallah wrote a public letter reflecting on what he believed was contradictory statements at the TRRC by ‘Jungler’ Omar Jallow. That is not to say that the work of the TRRC is being shaped by political pressures, but the efforts of political actors to alter perceptions of the Commission, particularly on social media, are having impacts on Gambians’ perceptions. Indirectly, “political parties do have a very big influence on how people perceive the work of the TRRC” was the view of one focus group respondent.

The APRC’s online and offline opposition to the TRRC process since its inception has been consistent: they believe that it is a witch-hunt against Jammeh. The party retains a strong base of support in the Foni region, home to the majority of ethnic Jola – of which Jammeh is a member. Even though they won just 5 seats in the 2017 parliamentary elections, this amounted to 16% of the vote share.

The political backdrop

The recommendations made by TRRC will be vital for its credibility. But there are concerns that the lack of action to implement the recommendations of the Janneh Commission was a worrying signal for what might happen with the TRRC, “the TRRC could become another Janneh: marred by selective implementation of recommendations”. Others were concerned that, “implementing recommendations made by TRRC may well be driven by what is most politically expedient given that they will come out in the same year as a presidential election. The formation of political coalitions could have significant influence on how recommendations are implemented”.

If Gambia moves from a first past the post presidential election system to one in which a candidate must win 50%+1 vote, as is proposed in the draft constitution, the likelihood of a candidate winning without forming a coalition, or at least seeking endorsements of others ahead of a second round, is slim. This will make the APRC, along with the Gambia Democratic Congress – which holds the second largest number of seats in the National Assembly – potential key powerbrokers, particularly for Barrow’s newly constituted NPP. The fact that the ruling party has retained several key Jammeh figures in government has led to fears that they could selectively apply the recommendations based on political calculations. Here there is a critical role for the National Assembly and civil society organisations to ensure appropriate scrutiny of the actions of the executive.

The APRC, publicly at least, has said it will not make coalitions with any party during the 2021 elections. But as one Jammeh-era victim notes that “if Barrow was to join forces with the APRC, for 2021 election, that would be a huge problem and it would destroy the credibility of the TRRC”. On the other hand, if the opposition wins power in 2021 “it will be keen to adopt many, if not all, of the TRRC recommendations directed at individual prosecutions as many of its members were victims”. But with the TRRC focused more on reconciliation than justice, such an approach could risk undermining those wider efforts.

Towards a conclusion

Will the recommendations be implemented by the government? This is a question already being asked by Gambians concerned about future political developments and frustrated at the poor provision of basic services that they feel have been neglected as the government devotes much of its focus to the various transitional justice processes. But arguably the more important question is whether the TRRC will make the right recommendations. Whilst political jockeying is not something that the Commission has any say over, they can ensure that the report clearly articulates its findings and outlines steps aimed at addressing them that includes recommendations for institutional reform as well as its take on who bears the greatest responsibility. As Madi Jobarteh notes, “this report can make or break The Gambia.”

If the TRRC is going to be successful it needs to grapple with key and difficult questions like what justice means and how it can be victim centred. It will also need to ensure that the recommendations it makes are legitimised by the public, as they will be key allies in pushing the government to include them in its white paper. The TRRC report will be a public document and to that end it will be crucial to build momentum behind a citizen-driven movement to ensure that whichever government is in power acts on its findings. Along with citizens, the National Assembly can also do more to ensure the TRRC report findings are actioned, “for now it [the Assembly] hasn’t really found its voice having been suppressed under Jammeh, as such it isn’t properly representing those they are elected to serve”.

Building relationships with civil society groups, community leaders, media, and lawmakers has been a feature of the TRRC’s work but more can be done in the coming months to better explain how the process will conclude and the ways in which various groups and citizens can support and champion the TRRCs work. An extension to the TRRC’s mandate may be requested, particularly if the Commission’s plans to hold public hearings and engagements at the community level are further affected by the Covid-19 outbreak. Public hearings were temporarily suspended but restarted on 8 June although the work of the Commission continued behind the scenes throughout.

Reparations, a critical part of the Commission’s mandate, must also be a key focus in the coming month as regulations to guide a more comprehensive framework are made public. Communicating how citizens can seek reparations is one of several critical components. The TRRC will also need to build a transparent and accountable system through which reparations are paid to avoid accusations of bias and work closely with MoJ to ensure more funds are secured, in a timely manner, that means the compensation provided is in some way reflective of the abuse suffered.

Source photo : Idayat Hassan