WATHI propose une sélection de documents sur le contexte économique, social et politique au Nigéria. Chaque document est présenté sous forme d’extraits qui peuvent faire l’objet de légères modifications. Les notes de bas ou de fin de page ne sont pas reprises dans les versions de WATHI. Nous vous invitons à consulter les documents originaux pour toute citation et tout travail de recherche.

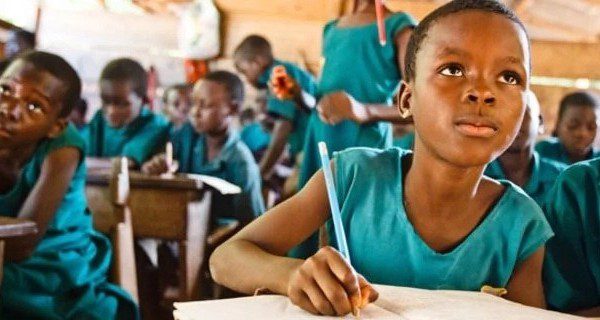

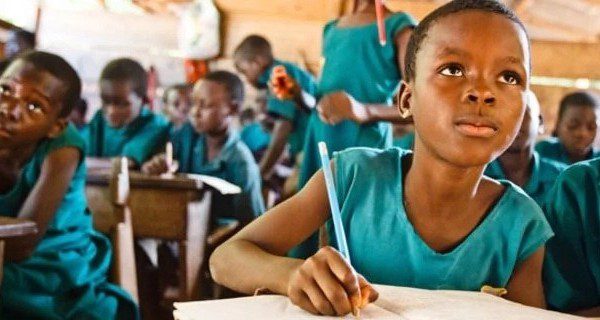

Au Nigeria, aller à l’école c’est combattre Boko Haram

Auteur (s) : Jacques Deveaux

Date de publication: 2018

L’éducation occidentale est une cible revendiquée par Boko Haram. Et le groupe a plutôt réussi dans son entreprise en faisant chuter la scolarité dans le nord du Nigeria. Pourtant la tendance s’inverse, favorisée par le recul des terroristes. Aller à l’école est désormais un acte de résistance. Mais les carences du pays en matière d’éducation restent patentes.

Selon l’Unicef, depuis 2009, Boko Haram a assassiné 2300 enseignants et détruit plus de 1400 écoles, généralement en les incendiant. En 10 ans, le groupe terroriste a provoqué l’exode de trois millions de personnes. Sa lutte contre l’éducation occidentale a sans doute connu son apogée lors de l’enlèvement des 276 lycéennes de Chibok en 2014. Après une chute massive des enfants scolarisés, moins 50% en dix ans, la tendance s’inverse. Une contre-offensive se développe et le champ de bataille est hors normes.

Classes en plein air

On en trouve l’expression dans ces classes en plein air au beau milieu d’un camp de réfugiés. «Aller à l’école est notre façon de combattre Boko Haram». Aiha a été privée d’école durant trois ans dans un camp de réfugiés au Niger. Aujourd’hui âgée de 19 ans, il lui reste un an d’études à suivre dans un internat de Maiduguri. «Ils n’aiment pas l’éducation, ils n’en veulent pas. Alors, juste en étudiant, nous les combattons.»

Selon l’Unicef, depuis 2009, Boko Haram a assassiné 2300 enseignants et détruit plus de 1400 écoles, généralement en les incendiant.

Les opérations humanitaires de scolarisation se multiplient, notamment dans le nord du pays, désormais un peu moins placé sous la coupe de Boko Haram. L’ONG Plan International espère scolariser plus de 150.000 enfants, notamment par un système d’écoles mobiles. Des enseignants se déplacent de villages en villages. Parallèlement, plus de 70 écoles en dur sont en cours de construction ou déjà construites.

L’éducation en ruine

Le Partenariat mondial de l’éducation dresse un tableau catastrophique du système éducatif au Nigeria. Le pays regroupe 20% des enfants non scolarisés dans le monde. La menace Boko Haram arrange bien des familles qui ne tiennent pas à envoyer leurs enfants à l’école. Cela coûte cher et elles n’en voient pas l’intérêt. Et l’enfant à l’école, ce sont des bras en moins à la maison.

Moins de la moitié des jeunes femmes savent lire. Dans le nord du pays, deux élèves sur trois sont illettrés. Des élèves qui dans les écoles n’apprennent rien, et Boko Haram n’est pas le seul responsable de cet état de fait.

«Dans ce pays, les écoles coraniques sont souvent les structures de l’éducation où un maître-marabout enseigne à lire le coran aux enfants. Souvent les enfants ne bénéficient que de cette éducation», explique Afrik.com. Dans l’Etat de Kano, le pouvoir local expérimente l’intégration de nouvelles disciplines dans l’enseignement coranique, histoire, géographie, anglais, etc.

Maîtres-marabout

Les régions du nord doivent aussi améliorer la qualité de l’accueil dans l’éducation, notamment en limitant à 40 le nombre d’élèves par classe. Vu leur grand nombre dans le territoire, ces écoles coraniques ont dû être également des cibles de Boko Haram. Et bon nombre des établissements détruits ne devaient probablement pas enseigner les maths ou l’anglais, ces piliers de l’éducation occidentale rejetée par les terroristes.

Alors Boko Haram s’en prend-t-il uniquement au symbole? Ne faut-il pas voir dans ces attaques, outre l’aspect idéologique, un moyen de recrutement de garçons en âge de combattre et d’enlèvement de futures épouses, comme à Chibok?

Grading Nigeria’s progress in education

Author (s) : Africa Check

Date of publication: 2018

In June 2016 President Muhammadu Buhari introduced a school-feeding programme to boost school enrolment. In northern Nigeria, another government programme has established more nomadic schools and “Almajiri” schools for destitute children. This factsheet gives an overview of education data in Nigeria.

School enrolment

Primary schools (grade 1 to 6). A total of 24,893,442 children were enrolled in Nigeria’s public and private primary schools in 2012. This had grown to 25.6 million by 2016, according to the education ministry. The year with the highest enrolment figure was 2013, when 26.2 million kids were enrolled in primary schools countrywide. In 2016, the net enrolment rate for primary schools was 65%.

This was the share of the country’s primary school age children who were actually enrolled in school. Lower secondary schools (form 1 to Enrolment in lower secondary schools was highest in 2014, when just over 6.2 million pupils were registered. In 2015 it dropped marginally, and in 2016 fell to fewer than 6 million.

Early childhood development

The Early Child Development Index measures the share of three- to five-year-olds who are developing appropriately in three out of four areas:

- Literacy and numeracy

- Physical

- Socioemotional

- Cognitive

Data from surveys by the UN’s child agency Unicef informs it.

Researchers asked parents 17 questions about their children. These included whether they attended an early education centre, were able to identify or name letters, and could pick up items. The children’s ability to follow directions in simple tasks and to get along with other kids were also assessed.

In 2011, the index was at 60.9%, moving up slightly to 61.2% in the 2016/17 survey.

“The index is very important as it shows the extent to which government, parents and other major stakeholders are affecting the general growth of a child,” said Moses Amosun, who teaches at the University of Ibadan’s department of early childhood and educational foundations.

Pupil-to-teacher ratio

In 2016, Nigeria had nearly 1.5 million teachers in public and private schools, according to the federal ministry of education:

- 764,596 primary school teachers

- 292,080 teachers in junior secondary schools

- 398,275 senior secondary teachers

Ratios in the Nigeria Education Management Information System show one qualified teacher for every 46 pupils in public primary schools, 29 pupils per qualified junior secondary school teacher and 16 pupils for one qualified teacher in senior classes.

Government funding

UNESCO recommends that developing countries like Nigeria should dedicate at least 15 to 20% of their spending to education. But since Nigeria’s return to democracy in 1999, the country has never budgeted more than 12% of its public resources to education.

In Nigeria’s 2018 budget, education is set to get N651.2 billion (US$1.88 billion), or about 7% of the total spend. Less than 20% of this will go to building new schools, buying learning equipment and other capital projects. “There is a way education connects to everything, but our leaders don’t seem to see that connection,” said Ogunwale Ogunlana.

L’éducation au Nigéria

Auteur (s) : Partneriat Mondial pour l’Education

Date de publication: 2017

Lien vers le document original

Le Nigéria est le pays le plus peuplé d’Afrique et abrite près de 20 % du total des enfants non-scolarisés dans le monde. Outre cette difficulté, la pression démographique se traduit par près de 11 000 naissances par jour, pesant ainsi lourdement sur les capacités du système à fournir une offre éducative de qualité.

Dans le Nord du pays, près des deux-tiers des élèves sont illettrés.

Les États de Jigawa, Kaduna, Katsina, Kano et Sokoto ont montré leur engagement à améliorer leur système éducatif, mais sont confrontés à de sérieuses difficultés, notamment un niveau élevé de pauvreté, un faible taux de scolarisation, des inégalités entre les sexes, un manque de qualité et de pertinence, de mauvaises infrastructures et conditions d’apprentissage.

Le Nigéria est le pays le plus peuplé d’Afrique et abrite près de 20 % du total des enfants non-scolarisés dans le monde

Autre obstacle, la menace directe pesant sur la scolarisation, en particulier celle des filles, du fait de l’insécurité politique qui se traduit par les activités d’insurgés et les attaques d’écoles. Chaque État a élaboré un plan sectoriel de l’éducation présentant ses priorités et ses objectifs.

État de Jigawa

Son Plan stratégique du secteur de l’éducation souligne 4 objectifs politiques :

- Améliorer l’accès et étendre les opportunités d’apprentissage.

- Assurer la qualité et la pertinence de l’offre éducative.

- Améliorer la planification et la gestion en matière d’éducation.

- Assurer un financement durable et une meilleure gestion financière.

Le plan sectoriel de l’éducation définit également 17 initiatives claires en soutien à ces objectifs politiques, notamment l’instauration de l’enseignement gratuit pour les filles à tous les niveaux, ainsi que pour les personnes ayant des besoins spécifiques.

État de Kaduna

Sa stratégie sectorielle de l’éducation à moyen terme pour la période 2015-2017 vise notamment à :

- fournir un accès à un enseignement de qualité à tous les enfants en âge d’aller à l’école, atteindre la parité entre les sexes et un ratio élèves-enseignant de 40 pour 1 par classe.

- améliorer la qualité de l’éducation afin que les élèves sachent définitivement lire, écrire et compter, et acquièrent les compétences de vie et une capacité cognitive.

- améliorer la performance à la fois à l’école et au niveau des examens publics assurant un meilleur taux de progression et un taux d’achèvement plus élevé pour tous les élèves.

- améliorer la planification et la gestion des services éducatifs et des établissements d’enseignement pour assurer une prestation efficace de l’éducation.

- s’assurer de la responsabilité de toutes les parties prenantes y compris des communautés, des organisations de la société civile et du secteur privé.

État de Kano

Son Plan stratégique de l’éducation s’articule autour de 5 domaines clés :

- assurer un accès équitable à l’éducation de base en traitant à la fois les facteurs d’offre et de demande.

- améliorer la qualité de l’éducation en réduisant la taille des classes, en augmentant la mise à disposition de matériels pédagogiques et en améliorant la qualité des enseignants.

- élargir les opportunités de formations techniques et professionnelles pertinentes pour répondre aux besoins de l’industrie et des communautés locales.

- augmenter progressivement le financement de l’éducation et instaurer un système de subventions aux établissements en appui à leur développement.

- s’assurer que toutes les écoles disposent de plans de développement, de comités de gestion et de conseils d’administration pour en améliorer la gouvernance.

État de Katsina

Son Plan stratégique du secteur de l’éducation souligne les objectifs politiques stratégiques et les interventions qui répondent aux 5 défis majeurs de son système éducatif que sont :

- la couverture inadéquate et le niveau d’accès insatisfaisant

- la faiblesse de la qualité et de la pertinence

- l’insuffisance et le délabrement des infrastructures

- l’inefficacité de la gestion et du système

- les financements et les ressources adéquates non durables.

Les interventions stratégiques comprennent une augmentation de la participation communautaire, du plaidoyer et de la sensibilisation et, pour les enseignants, l’amélioration de la sécurité sociale et une offre de nouvelle formation.

État de Sokoto

Son Plan stratégique du secteur de l’éducation a fixé 4 objectifs prioritaires à savoir :

- améliorer le rendement de l’apprentissage pour les enfants au niveau du préscolaire dans les 23 zones de gouvernement local.

- contribuer à l’amélioration du taux net de scolarisation, de rétention dans le système scolaire et du niveau d’instruction dans le primaire.

- assurer une éducation de base, une formation professionnelle et des compétences pratiques aux enfants non-scolarisés et aux femmes, à travers l’éducation non formelle.

- augmenter le taux de scolarisation et de rétention des enfants dans le système scolaire.

Le secteur prévoit également 4 domaines clés d’intervention, notamment la construction d’écoles, l’acquisition de matériels pédagogiques essentiels pour l’apprentissage, la fourniture d’équipement et de machines et le renforcement des capacités.

Education in Nigeria

Author (s) : World Education News+ Reviews

Date of Publication: 2017

Introduction

Almost one in four Sub-Saharan people reside in Nigeria, making it Africa’s most populous country. It’s also the seventh most populous country in the world, one with ongoing growth. The country will likely remain a dynamic growth market for international students. This is largely because of the overwhelming and unmet demand among college-age Nigerians.

Nigeria’s higher education sector has been overburdened by strong population growth and a significant ‘youth bulge and rapid expansion of the nation’s higher education sector in recent decades has failed to deliver the resources or seats to accommodate demand: A substantial number of would-be college and university students are turned away from the system. About two thirds of applicants who sat for the country’s national entrance exam in 2015 could not find a spot at a Nigerian university.

International Mobility Trends: the Top African Sender of Students

Nigeria is the number one country of origin for international students from Africa: It sends the most students overseas of any country on the African continent, and outbound mobility numbers are growing at a rapid pace. According to data from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS), the number of Nigerian students abroad increased by 164 percent in the decade between 2005 and 2015 alone – from 26,997 to 71,351.

Nigeria’s higher education sector has been overburdened by strong population growth and a significant ‘youth bulge’

In the short term, Nigeria’s oil price-induced fiscal crisis is likely to affect outbound student mobility. As many as 40 percent of Nigerian overseas students are said to rely on scholarships, many of which were backed by oil and gas revenues. The push factors that underlie the outflow of students in Nigeria are fundamentally unchanged. These include:

- The failure of Nigeria’s education system to meet booming demand

- The often poor quality of its universities

- Rapid growth in the number of middle class families who can afford to send their children overseas

Given those drivers, it seems unlikely that the crisis will lead to a sharp and prolonged downturn of international student numbers.

Destination countries

Due to colonial ties and a shared language, the United Kingdom has long been the favorite destination for Nigerian students overseas with numbers booming in recent years. Some 17,973 Nigerian students studied in the UK in 2015.

The Nigerian government has the official goal to universalize free basic education for all children. Yet, despite recent improvements in total enrollment numbers in elementary schools, the basic education system remains underfunded

In line with a general shift towards regionalization in African student mobility, Nigerian students in recent years have been increasingly studying in countries on the African continent itself. Ghana has recently overtaken the U.S. as the second-most popular destination country, attracting 13,919 Nigerian students in 2015, according to the data provided by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS). Another country that has more recently emerged as a popular destination for Nigerians, especially among those from the Muslim north, is Malaysia.

Crisis in elementary schooling

Like the country’s education system as a whole, Nigeria’s basic education sector is overburdened by strong population growth. A full 44 percent of the country’s population was below the age of 15 in 2015, and the system fails to integrate large parts of this burgeoning youth population. According to the United Nations, 8.73 million elementary school-aged children in 2010 did not participate in education at all, making Nigeria the country with the highest number of out-of-school children in the world.

The lack of adequate education for its children weakens the Nigerian system at its foundation. To address the problem, thousands of new schools have been built in recent years. The Nigerian government has the official goal to universalize free basic education for all children. Yet, despite recent improvements in total enrollment numbers in elementary schools, the basic education system remains underfunded; facilities are often poor, teachers inadequately trained, and participation rates are low by international standards.

Senior secondary education

Senior Secondary Education lasts three years and covers grades 10 through 12. In 2010, Nigeria reportedly had a total 7,104 secondary schools with 4,448,981 pupils and a teacher to pupil ratio of about 32:1. Reforms implemented in 2014 have led to a restructuring of the national curriculum. The new curriculum has a stronger focus on vocational training than previous curricula, and is intended to increase employability of high school graduates in light of high youth unemployment in Nigeria. In addition to public schools, there are a large number of private secondary schools, most of them expensive and located in urban centers.

Senior school certificate examination

At the end of the 12th grade in May/June, students sit for the Senior School Certificate Examination (SSCE). They are examined in a minimum of seven and a maximum of nine subjects, including mathematics and English, which are mandatory. Successful candidates are awarded the Senior Secondary Certificate (SSC), which lists all subjects successfully taken.

SSC examinations are offered by two different examination boards: the West African Examination Council and the National Examination Council (NECO). The examination is open to students currently enrolled in the final year of secondary school, as well external private candidates (in the November/December session only). The SSCE grading scale is as follows for both WAEC and NECO administered examinations:

Admission to public universities in Nigeria is competitive and based on scores obtained in the Unified Tertiary Matriculation Examination as well as the SSCE results. grades.

Vocational and Technical Education

The Nigerian education system offers a variety of options for vocational and technical education at both the secondary and post-secondary levels. To combat chronic youth unemployment, the Federal Ministry of Education presently supports a number of reform projects to advance vocational training, including the “vocationalization” of secondary education and the development of a National Vocational Qualifications Framework by the National Board for Technical Education, similar to the qualifications frameworks found in other British Commonwealth countries.

Not Enough University Seats

According to the statistics JAMB provides on its website, a total of 1.579,027 students sat for the UTME exam in 2016. 69.6 percent of university applications were made to federal universities, 27.5 percent to state universities, and less than 1 percent to private universities. The number of applicants currently exceeds the number of available university seats by a ratio of two to one. In 2015, only 415.500 out of 1.428,379 applicants were admitted to university, according to the data provided by JAMB.

This admission ratio, low as it may be, is a significant improvement versus 10 years ago when the ratio was closer to one in ten for university entry. But the admissions crisis continues to be one of Nigeria’s biggest challenges in higher education, especially given the strong growth of its youth population. Nigeria’s system of education presently leaves over a million qualified college-age Nigerians without access to postsecondary education on an annual basis.

One Key Challenge: Underfunding

One of the most pressing problems for Nigeria’s higher education system remains the severe underfunding of its universities. The Federal government, which is responsible for sustaining public universities, has over the past decade not significantly increased the share of the government budget dedicated to education, despite exploding student numbers. Between 2003 and 2013 education spending fluctuated from 8.21 percent of the total budget in 2003 to 6.42 percent in 2009, and to 8.7 percent in 2013.

In 2014, the government significantly increased education spending to 10.7 percent of the total budget, but it remains to be seen if this share can be maintained following the oil price-induced fiscal crisis. Recent reports suggest that current spending levels have already decreased well below 10 percent.

Although rankings are a notoriously poor proxy for university quality, they do provide the best relative guide available. It’s thus worth noting that, in 2017, only one of Nigeria’s universities is currently listed among the top 1,000 in international university rankings in the Times Higher Education Ranking – the University of Ibadan at 801.

Another Key Challenge: Academic Corruption and Fraud

While corruption is a covert activity that is difficult to measure, Nigeria scores low on the global “Corruption Perceptions Index” published by the organization Transparency International. The 2016 report places Nigeria at 136th place among 176 countries.

In 2013, the federal government announced plans to create six regional ‘mega-universities’ with the capacity to admit 150,000 to 200,000 students each

Nigeria’s education sector is particularly vulnerable to corruption. As corruption scholar Ararat Osipian noted in 2013, “[l]imited access to education [in Nigeria] has no doubt contributed to the use of bribes and personal connections to gain coveted places at universities, with some admissions officials reportedly working with agents to obtain bribes from students. Those who have no ability or willingness to resort to corruption face lost opportunities and unemployment.” The extent of fraud in university applications has caused the Council to develop an elaborate scratch-card system that utilizes an online pin-code verification method to verify the authenticity of exam results.

Promised Reforms

The NUC has, in recent years, closed a large number of illegal degree mills. In 2013, it shut down 41 such entities, and in 2014 the Council closed an additional 55 degree mills while investigating 8 additional schools. For current information on degree mills, the NUC has started to publish a “list of illegal universities”, most recently in 2016.

Other government reforms and initiatives have sought to improve the Nigerian higher education system as well. These include the upgrade of some polytechnics and colleges of education to the status of degree-awarding institutions, the approval and accreditation of more private universities, and the dissemination of better education-related data.

In 2016 alone, the federal government granted approval for the establishment of eight new private universities. In 2013, the federal government announced plans to create six regional ‘mega-universities’ with the capacity to admit 150,000 to 200,000 students each. As of February 2017, however, there was no indication that this ambitious project would be realized in the near future.

Nigeria universities: Where students don’t know if they will graduate

Author (s) : British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)

Date of publication: 2019

The futures of more than a million Nigerian university students are on hold as a lecturers’ strike drags on less than a month before a presidential election, as Yemisi Adegoke reports from Lagos.Olamide Tejuoso had been looking forward to the start of 2019. She was expecting to be a fresh graduate beginning her career with a paid internship at a media company. The first step in realising her dream of becoming a writer after four years of studying at the University of Ibadan. But instead of excitement, the communications student feels frustrated because of the ongoing strike by the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU).

Students at Nigeria’s state-funded universities have not resumed their studies due to an indefinite nationwide strike by academic staff that began in November. The union has accused the government of failing to honour past agreements over the redevelopment of tertiary education. They are also protesting about poor facilities, poor funding and an alleged plan to increase tuition fees. There have been talks between the union and the government but negotiations are dragging on.

‘Can’t make plans’

Meanwhile, the future of Nigeria’s 1.2 million federal university students is in limbo. “It’s depressing,” says Ms Tejuoso. “As a final year student, you have all these plans, but you’re not seeing the reality.” “I should have graduated last December, but because of this strike I’m limited. I can’t do any major travel, I can’t take any major job because I don’t know when we’re going to resume.”

She now keeps herself occupied by writing and trying to work on her final project. During previous strikes students have come out to support the lecturers in their bid to improve the university sector. Ms Tejuoso has also enrolled in a sewing class, but she is anxious and desperate to get back to university.

Students at Nigeria’s state-funded universities have not resumed their studies due to an indefinite nationwide strike by academic staff that began in November

“We’ve had more than two months [of the strike] already and it’s making the future look so bleak,” she says. “We don’t know what’s going to happen. Because of the elections, [resuming in] February is in doubt. We don’t even know what the future holds for us.” ASUU president Biodun Ogunyemi, who himself has two children at public universities, says the strike is to secure the future of tertiary education, and ultimately the students’ future.

‘Restore dignity’

“We have always told our students and their parents what we’re doing is in their own interests,” Prof Ogunyemi says. “We don’t want them to earn certificates that will be worthless, we don’t want them to get an education they can’t be proud of, we want the restoration of the integrity of their certificates.”

One of the major demands of the union is the implementation of past agreements and the spending of $2.7bn (£2.1bn) in total to revamp universities. Annually, the government currently allocates about $1.8bn (£1.4bn) to the education sector overall, which accounts for 7% of federal government spending. Federal universities get nearly $750m of that. But the lecturers say that it is not enough.