Business Pathways to the Future of Smallholder Farming in the Context of Transforming Value chains

Author(s)

Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), Ousmane Badiane, John Ulimwengu, International Food Policy Research Institute

Introduction

While analyzing business pathways to the future of smallholder farming in the context of transforming value chains, it is important to consider changes in strategies over time. In the mid-1960s India, Indonesia and the Philippines promoted smallholder-driven agricultural intensification through massive public investments that included price guarantees to raise smallholders’ incomes (Birner & Resnick, 2010).

In Africa, policies were dominated by structural adjustment policies of the 1980s and 1990s, with governments facing greater conditionality structures and smallholders facing lower and more volatile prices and less favorable terms of trade (Dorward, Kydd, Morrison, & Urey, 2004). These political constraints on state support to agriculture explain some of the challenges faced in Africa today, including institutional and governance deficit; lack of infrastructure to support production, processing and commercialization; weak integration of value chain components; and absence of opportunities for uptake of innovations (Dawson, Martin, & Sikor, 2016).

he thorny problems of promoting the growth of incomes in smallholder agriculture in Africa have been exhaustively examined in literature inspired by a variety of concerns and ideological biases. For example, research points to urban bias where cities received disproportionate shares of public services and investments, and heavy net taxation on agriculture (Lipton, 1977; Krueger, Schiff, & Valdés, 1991). One strand of the literature emphasizes the need for smallholders in Africa to become increasingly involved in the production for sale of high value-to-weight commodities that also have high value-added, especially for export markets.

Hausmann and Rodrik (2003) and Easterly and Reshef (2010) indicate that the rewards from identifying highly successful exports are always great. Promoting growth in smallholder agriculture in Africa through increased participation in growing world markets for high-value commodities is expected to require significant vertical integration of smallholders into the value chain (Delgado, 1999).

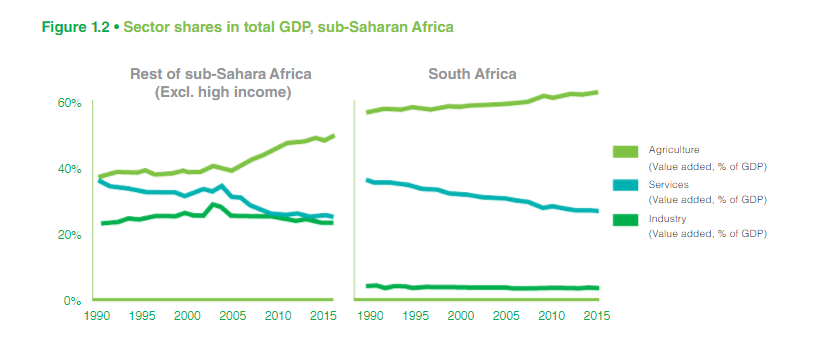

However, the type of agricultural transformation relevant today is very different from the kind of green revolution transformation that Africa aspired to in earlier decades. The new agenda needs to be much more focused on a market driven, business agenda that encompasses the entire food system, not just agricultural production. But Africa is at a crossroads: should it go for a food system transformation led mainly by large commercial farms and large agribusinesses, as in many rich countries? Or should it go for an “inclusive” transformation based on commercial smallholder farms and SMEs along value chains.

A large farm, large agribusiness approach would leave millions of small farms and businesses without adequate livelihoods, whereas an inclusive approach could engage more of them in productive employment, create more attractive jobs for young people, help reduce poverty, inequality and food insecurity, and contribute to better nutrition outcomes. But an inclusive approach would also require greater public sector involvement and investment, and hence government commitment to the transformation agenda.

A key area of challenge related to efforts to deepen and broaden the integration of smallholder farmers trying to integrate into agribusiness value chains includes a rapidly changing and increasingly complex market environment. The increasing globalization of agricultural markets presents African smallholders with considerably more complex challenges than those faced by Asian producers during the Green Revolution era.

African smallholders today need not only to produce more efficiently, but also to contend with far more logistically complex and competitive markets. Growing specialization in distribution channels and logistics; rapidly changing and differentiated consumer preferences; and increasingly complex norms, standards, and other technical specifications place increasing demands on the production and management skills of the average smallholder (Berg & Jiggins, 2007)

Food Production by 2050 and the Role of Smallholder Farming

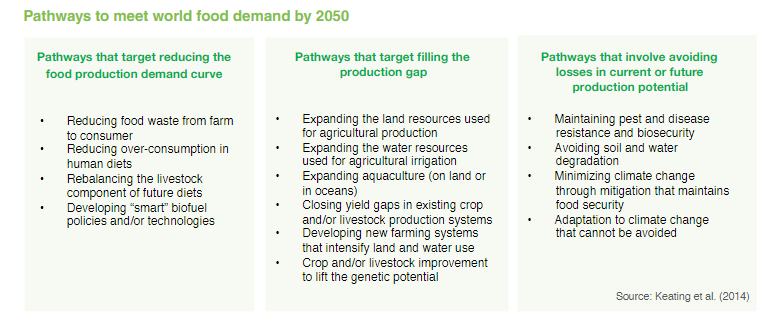

Sustaining recent growth in African agriculture is essential for the continent’s ability to achieve food security and maintain broader economic growth in the future. Fast-rising food demand from growing and urbanizing populations presents an opportunity for African farmers, if they can ensure the required productivity and production increases. However, the effects of climate change threaten farmers’ ability to maintain and accelerate agricultural growth. Sulser et al. (2014) use the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) International Model for Policy Analysis of Agricultural Commodities and Trade (IMPACT1) to project future trends in food production in Africa, and the likely impacts of climate change on production.

Using unique farm-size distribution data, Herrero et al. (2017) find that globally, small and medium farms (≤50 ha) produce 51–77% of nearly all commodities and nutrients considered in their study. Their study shows much heterogeneity across regions and land size. While large farms (>50 ha) dominate production in North America, South America, Australia and New Zealand where they contribute between 75% and 100% of all cereal, livestock, fruit production, and most other commodities, small farms (≤20 ha) produce more than 75% of most food commodities in SSA, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and China. Moreover, very small farms (≤2 ha) are important and have local significance in SSA, Southeast Asia, and South Asia, where they contribute around 30% of most food commodities and are managed by millions of smallholder farmers. The Herrero et al. (2017) findings also suggest that farms with less than 20 ha produce most of the essential nutrients (>80%) in SSA while farms smaller than 2 ha produce more than 25% of the nutrients.

Modernizing Smallholders’ Agribusiness Value Chains

Integrating Smallholder Farmers into Transforming Value Chains

Historically, geographic distance and diseconomies of scale have made the cost of doing business with smallholder farmers prohibitively high. Except for producers of major traditional and some high-value export commodities, most African smallholders are isolated from agricultural value chains for a variety of reasons, most of which center on their small scale, their geographic isolation, and their lack of capital. The few cases where these problems have been overcome are usually instances in which farmers have been linked to public or private sector firms or operators who have provided a bridge to other value chain actors. These firms provide some degree of credibility to smallholders as business partners to input dealers, technology providers, traders, financial services providers, processors, and exporters.

There are growing commitments by multinational corporations, NGOs, and social enterprises aimed at empowering smallholder farmers and SMEs and connecting them to global corporate value chains (Clinton Global Initiative, 2016):

- In 2015 the Hershey Company committed to train 7,500 smallholder farmers in Ghana on improved agronomic practices and empower them to supply commercial markets with groundnuts

- In 2015 Unilever, Acumen, and the Clinton Giustra Enterprise Partnership committed to improve the livelihoods of over 300,000 smallholder farmers, by scaling social enterprises and linking them to inclusive global supply chains and distribution networks.• In 2014 Sodexo committed US$1 billion in spending to bring more micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), especially those owned and operated by women, into its global supply chain.

- In 2011 Heineken committed to locally source 60% of the raw materials used in its African beer brands by 2020.

Many projects and programs that target smallholder farmers are being deployed in many parts of Africa. A key weakness is that many of them target an isolated problem for a single segment of a given value chain, often in a specific geographical area. They offer solutions that are neither replicable nor scalable. Effectively linking farmers, in numbers large enough to make a difference, to modern value chains requires integrated solutions that deal with all major interfaces between smallholders and other value chain actors.

The 21st century producer organization should be more than an advocate or marketing body. With modern ICTs at their fingertips, such organizations can upgrade their skills and their operations to offer a comprehensive set of services to their members. Through facilitation from SPOs, the potential of African smallholders can be harnessed to capture more of the rapidly expanding staples food markets to generate income, create wealth and transform traditional farming and rural areas.

Optimizing the Role of Producer Organizations in Promoting the Integration of Smallholders into Agricultural Value Chains

Increasing globalization presents African smallholders with considerably greater challenges than those faced by Asian producers during the Green Revolution era. African smallholders today not only need to produce more efficiently, but also to contend with far more complex and competitive markets. Growing specialization, rapidly changing consumer preferences and increasingly intricate technical specifications place significant demands on the average smallholder. Institutional and technical innovations around empowerment of and service provision to smallholder farmers therefore constitute key components of future agricultural transformation strategies.

To achieve adequate scale economies and market power while retaining independent ownership, smallholders could resort to the creation of collective governance forms represented by agricultural cooperatives (Valentinov & Tortia, 2012). Cooperative organizations thus appear to be an essential institution for inclusive agricultural development in rural Africa. This explains why cooperative organizations have been showing consistent growth throughout Africa over the past decade (Wanyama et al., 2008).

In fact, empirical evidence (Bernard, Taffesse, & Gabre-Madhin, 2008; Bernard, Collion, DeJanvry, & Rondot, 2008; Bernard et al., 2010; Hill, Bernard, & Dewina, 2008) shows that agricultural cooperatives are found in every other village in selected West African countries and in one-third of villages in selected East African countries, involving up to 75% of farm households in a given village. Data from rural Ghana reveal that approximately 10,000 SPOs existed in 2010, comprising almost 400,000 farm households (Salifu, Francesconi, & Kolavalli, 2010).

Improving Market Intermediation, Financial Services and Technology Innovation

The integration of smallholders into agricultural value chains therefore requires the transformation and operational diversification of producer organizations through acquisition of the necessary technical, commercial, and financial resources to enable them to efficiently and effectively fulfill all the major technology, market, and financial needs of their membership. In other words, they need to develop into business-oriented entities that can serve as credible business partners to other actors along the value chain. In general, smallholder cooperatives have acquired technical and commercial skills through advisory and training services provided by public or private organizations, including contracting parastatals or private firms.

However, cases of successful integration of smallholders into value chains do exist. Examples include the groundnut and cotton chains in West Africa where smallholders have been able to produce and sell competitively to global export markets. Common to all these cases is the important role played by a third party, mostly public or private sector firms, in providing a host of services facilitating value chain access. For example, food retailers impose protocols relating to pesticide residues, field and pack house operations, and traceability (Narrod et al., 2009). Therefore, to enable smallholders to remain competitive, new institutional arrangements are required. In particular, public–private partnerships can play a key role in creating farm to fork linkages that can satisfy market demands for food safety, while retaining smallholders in the supply chain (Narrod et al., 2009).

To encourage the development of producer organizations into effective “chain actors”, primarily as “product specialists”, which is often the first step in integrating smallholders who are predominantly outside of the value chains, these organizations need to engage in relationships with upstream and downstream firms in the agri-food chain.

The starting point of transaction cost economics is the observation that the complexity of the real world makes it too costly to describe all relevant contingencies regarding the exchange ex ante in a contract. Contracts are therefore necessarily incomplete. Williamson (1985) argues that this causes problems when the parties involved in the exchange make specific, irreversible (or sunk) investments, that is, investments which have a significantly higher value within the relationship than in alternative uses. This puts the investor in a weak bargaining position regarding the division of ex post surplus, because the incompleteness of the contract prevents all eventualities from being covered ex ante.

A possible strategy to promote smallholder integration into value chains, either for domestic or global markets, would target the development of three categories of required skills for smallholder organizations:

1. The development of technical skills to enable them to: (i) source and apply improved technologies by engaging with technology providers; and (ii) claim a greater share of the added value through processing by meeting the technical requirements of third party processing firms or mastering the technical operations of their own plants.

2. The development of commercial skills for them to acquire the capacity to: (i) work with financial services providers to meet the capital and insurance needs of their members; (ii) strengthen their bargaining positions with traders and exporters; and, where possible, (iii) to competitively expand their participation in trading and exporting activities.

3. The development of organizational and institutional skills to: (i) avoid erosion of social capital; (ii) achieve the level of governance and coordination effectiveness required by greater participation in value chains; and (iii) improve the effectiveness and efficiency of service delivery to their members.

Concluding Remarks

The rapid transformation of staple food value chains, driven by urbanization and rising incomes, represents considerable market opportunities for African smallholder farmers. At the center of this transformation are a large and growing number of small processing enterprises and an emerging modern packaging, distribution and marketing sector that is responding to the changing dietary trends among middle-income urbanites. Demand in urban food markets is not only much larger but also projected to grow considerably faster than demand for African agricultural exports to foreign markets. If they can respond to the needs of modern value chains, smallholders across Africa will capture a significant part of this future demand. The incremental income that this represents is estimated in the billions of dollars.

Whether the above scenario will become reality depends on continued progress on several fronts. Investments in institutional and firm-level innovation capabilities will be required to support enterprise creation and growth in the middle segments of the value chains. Smallholder farmers will need to become credible business partners with other value chain operators. No other options exist to realize this at scale without the intermediation of stronger farmer organizations with the required commercial and technical skills.

Overcoming the infrastructural, institutional, and technological obstacles to business-oriented organizations with sufficient reach to support the millions of dispersed smallholder farmers using conventional approaches would take too much time and money to allow local farmers to capture a sizeable part of the surging urban demand. Countries will have to find innovative ways of harnessing modern technologies, in particular ICTs to reduce the cost and time of modernizing farmer organizations and connecting smallholder farmers to other value chain segments. This will require a successful transition from the myriad of isolated applications that focus on fragmented problems of specific value chain segments to products that offer integrated solutions to business operations across several value chain segments.

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.