Why an Inclusive Agricultural Transformation is Africa’s Way Forward

Author (s)

Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), Peter B. R. Hazell, Independent Researcher

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview to the 2017 Africa Agriculture Status Report (AASR). It begins by reviewing the case for prioritizing agriculture, arguing that Africa’s recent pattern of growth based on “urbanization without industrialization” has increased rather than reduced the need for an agricultural transformation. It argues that many things are now coming together in ways that give Africa the need, the opportunity, the means, and the ambition to transform its agriculture sector. The question now is not whether Africa needs an agricultural transformation, but rather what kind of transformation it needs and how to achieve it.

African economies experienced unprecedented rates of economic growth over 2005–2015, as well as rapid urbanization. However, unlike Asia, this has not led to a shift of workers from agriculture to urban-based industries, especially export manufacturing. Nearly all the non-agricultural growth has been in the services sector, and while this has created many additional jobs, they are mostly low productivity jobs.

This pattern of urbanization without industrialization offers limited scope for more rapid and sustained growth in national per capita incomes, highlighting the need for more proactive efforts by governments to promote growth in higher productivity segments of the economy, and shifting more workers into those activities. Renewed efforts to modernize the agriculture sector, or at least large parts within it, could make a valuable contribution to national economic growth in many countries, and to poverty reduction.

However, the type of agricultural transformation relevant today is very different from the kind of green revolution transformation that Africa aspired to in earlier decades. The new agenda needs to be much more focused on a market driven, business agenda that encompasses the entire food system, not just agricultural production.

But Africa is at a crossroads: should it go for a food system transformation led mainly by large commercial farms and large agribusinesses, as in many rich countries? Or should it go for an “inclusive” transformation based on commercial smallholder farms and SMEs along value chains. A large farm, large agribusiness approach would leave millions of small farms and businesses without adequate livelihoods, whereas an inclusive approach could engage more of them in productive employment, create more attractive jobs for young people, help reduce poverty, inequality and food insecurity, and contribute to better nutrition outcomes. But an inclusive approach would also require greater public sector involvement and investment, and hence government commitment to the transformation agenda.

Why Agriculture is still Critical for Africa’s Economic Transformation

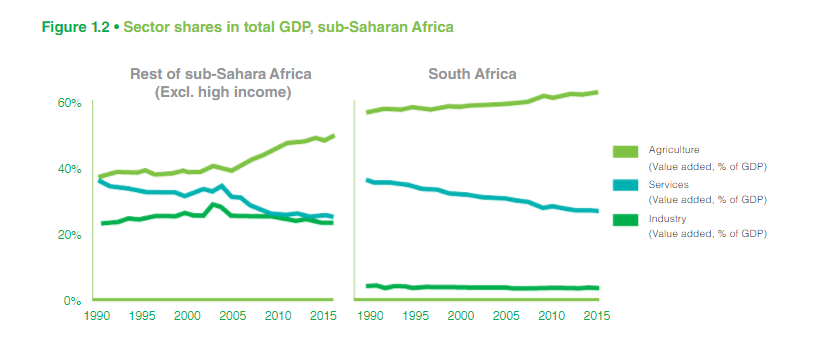

Economic growth accelerated across much of Africa during 2005–2015 (Figure 1.1). Although outpaced by Asia, the rates of growth achieved were nevertheless unprecedented for many African countries, and led to a period of euphoria among many experts in which African economies seemed finally to be taking off. As should be expected, this growth has been accompanied by structural changes in the composition of national economies (Figure 1.2). Agriculture has shrunk as a share of both national gross domestic product (GDP) and the total labor force. A surprise has been the rapid urbanization of Africa.

This urbanization is surprising because, unlike the economic transformations of China and some other fast growing Asian economies, workers have not moved into manufacturing. Rather, in much of Africa, industry at large, including manufacturing, has remained at while workers have moved into a burgeoning and mostly urban-based services sector. The services sector is now the largest sector in Africa, and already accounts for over half of Africa’s total GDP (Figure 1.2; Rodrik, 2016). This pattern of growth has been characterized as “urbanization without industrialization”.

This pattern of economic transformation has some problems. For starters, it turned out that Africa’s growth spurt was driven more by a commodity price boom than any real improvement in its economic fundamentals, and when prices turned so did economic growth rates. Also, the growing dependence on the services sector does not offer a sustainable pathway to rapid economic growth. This is because most services are informal, labor-intensive activities, whose labor productivity is little if any better than traditional agriculture. Unlike manufacturing, which faces an elastic demand for its outputs, either through exports or import substitution, the services that are produced are mainly for the domestic market (i.e., they are non-tradables), so their growth is constrained by growth in national demand.

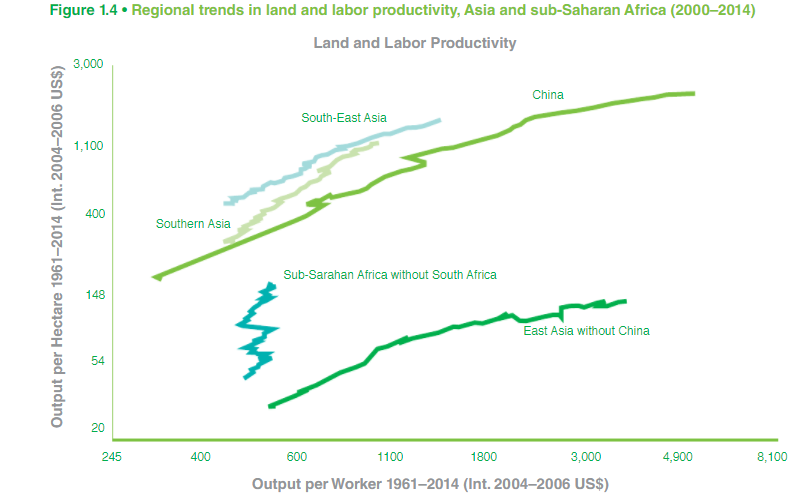

Demand, in turn, depends on growth in national per capita incomes, population sizes, and changing patterns of consumption associated with the movement of people from rural to urban lifestyles. This pattern of transformation can only take Africa so far, and will at best lead to modest rates of national economic growth (Rodrik, 2016; McMillan, Rodrik, & Sepúlveda, 2016). How can Africa accelerate and sustain its growth rate and become more of a hare than a tortoise? Growth in GDP per capita is highly correlated with growth in labor productivity, and there are two basic sources of potential growth in labor productivity.

One is growth of labor productivity within sectors. The other is growth of high labor productivity sectors like manufacturing and the movement of workers to those sectors from lower productivity ones. So far growth in labor productivity in Africa has arisen mainly through increases in “within-sector” labor productivities (Badiane & Makombe, 2014; McMillan et al., 2016). While continued productivity growth within sectors is likely, it is generally quite modest, and faster economic growth needs to come from growing the more productive parts of the economy and facilitating the movement of workers to those activities.1 What are the prospects for that?

Industry

There are reasons to be pessimistic about Africa’s potential to become a major hub of export manufacturing, at least at a time when China and other Asian countries are ooding world markets with low cost manufactured goods.

Niche opportunities undoubtedly exist for some African countries to develop export manufacturing, and those opportunities should of course be pursued. But for most of Africa, more promising short to medium-term prospects lie at home and particularly in the growth of small and medium-sized manufacturing firms which can supply growing domestic and regional markets. One particular promising opportunity lies with food industries, which face a rapidly growing urban market for processed and pre-cooked foods.

Services

The diffculty with the informal services sector is that it has relatively low labor productivity, in some cases no better than traditional agriculture. Although opportunities may exist for developing pockets of modern services that have higher labor productivity, it is unlikely that they can achieve the scale needed to substitute for the development of modern manufacturing and agriculture if Africa is to grow faster.

Agriculture

This brings us to agriculture, which still has considerable potential for growth in Africa. Here are three good reasons to be optimistic about agriculture’s potential:

- Africa still has the resource base that if more intensively farmed could easily produce another 100 million tons of grain equivalents each year, equivalent to adding another US corn belt to the global supply and turning Africa into a net agricultural exporter. This potential is evidenced by the low yields Africa currently achieves compared with those of similar agro-ecological zones (FAO & World Bank, 2009), experimental trials, and best farmer practices (Jirström, Andersson, & Djurfeldt, 2011). There is also considerable untapped irrigation potential2 and remaining uncultivated land that could be brought into production

- Demand for food is growing fast. Most African countries are still growing despite the slowdown induced by the decline in commodity prices in 2016, and the medium-term outlook is good for continued growth in international, regional and domestic markets. Africa’s demand for food is projected to more than double by 2050 , driven by population growth, rising incomes, rapid urbanization, changes in national diets towards greater consumption of higher value fresh and processed foods, and more open intra-regional trade policies, all of which are helping create new opportunities for Africa’s farmers.

- Agriculture is also the best sector for addressing much of the remaining poverty in Africa. Since most farmers are smallholders, many of whom are poor, and increases in agricultural output help keep food prices low, small farm-led agricultural development typically has a big impact on poverty. Thirtle, Piesse and Lin (2003) estimate that a 1% increase in crop productivity reduces the number of poor people by 0.72 % in Africa and by 0.48% in Asia. Studies that compare growth–poverty elasticities across sectors typically and much higher elasticities for agriculture than for non-agriculture (Christiaensen & Demery, 2007; World Bank, 2007).

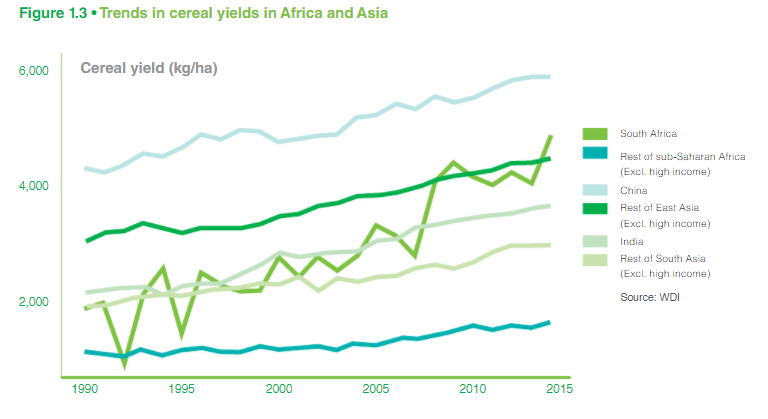

- Although Africa’s agricultural growth rate improved after 2005, averaging about 7% per annum, this was driven more by a commodity price boom and expansion of the cropped area rather than by improvements in the underlying fundamentals. Africa’s cereal yields started to grow after 2000,5 but still remain low compared to other countries, and the gaps are widening (Figure 1.3).

What kind of Agricultural Transformation does Africa Need

The situation in Africa today is very different from that in Asia at the time of its Green Revolution, and requires a different kind of agricultural transformation. Some key differences:

- Despite occasional shocks like the world food crisis of 2007, the global food balance is much more favorable today than in the immediate Green Revolution era, and international trade in agricultural commodities has soared. This means that African countries have more freedom to meet their food needs through a mix of own production and international trade, and can focus on producing those agricultural commodities which best match their resource endowments and export opportunities.

- African food systems have evolved rapidly in recent years in response to urbanization, rising incomes and changing diets. Although there is considerable country variation, overall there has been a huge increase in the volume of foods that pass through the food system, possibly by a factor of six- to eightfold since 1970

- Changing rural demographics are reaching tipping points that require attention. Rural populations continue to grow across much of Africa, and are projected to do so until at least 2050.

- The development agenda has moved on. While food security was the primary goal during the Green Revolution, the agenda of the international community has evolved and development assistance today seeks to address a broad range of economic, environmental and social goals, as encapsulated in the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Improved nutrition and health have emerged as particularly important issues for agriculture and food systems.

Commercializing Small Farm Agriculture

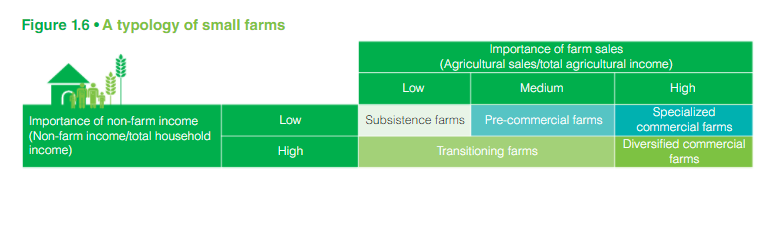

Coping with the diversity of small farmsAfrica’s small farms are diverse and face varying livelihood prospects depending on their own assets and aspirations, as well as their regional and country contexts. There are few “one-size-fits-all” policies for assisting small farms, and hence this diversity cannot be ignored. However, not all small farms can hope to succeed as commercial farms in the future. Those that can need the right kinds of business support, while those who are unlikely to succeed as commercial farmers need different types of assistance. Targeting the right kinds of assistance requires a typology and a means of recognizing or targeting different types of small farms in programs and projects.

- Commercial smallholder farmers are successfully linked to value chains and run their farms on a business basis. They may be full or part-time farmers

- Small farms in transition have favorable non-farm opportunities and obtain much of their income from non-farm sources. In the absence of significant new opportunities in farming that can give a competitive return to their labor and capital as non-farm opportunities, many transition farmers are likely to leave farming altogether or, if they continue to live on their farms, farm largely for their own consumption.

- Subsistence-oriented small farms are marginalized for a variety of reasons that are hard to change, such as ethnic discrimination, sickness, age, or being located in remote areas with limited agricultural potential. Many of the same factors that prevent them from being more successful farmers also prevent them from accessing non-farm jobs and becoming transition farmers. Subsistence-oriented farms frequently sell small amounts of produce at harvest to obtain cash income, but are typically net buyers of staple food over the entire year

- The business agenda is not just about improving cereal yields, valuable though that can be. Most small farms are too small to prosper by growing cereals on a commercial basis, even if they could double their yields.

- Another new thing is the changed business environment prevalent in today’s food systems, and the need for small farmers to build stronger business links with private sector enterprises

- There is also new interest by large international agribusinesses in Africa’s food chains, as exemplified by the Grow Africa Investment Forum and the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition. Although an inclusive approach to the transformation calls for an emphasis on SMEs, large agribusiness still has some important functions to perform.

- Climate change is emerging as a real game changer that requires an adequate policy response. Average crop yields are falling with shorter growing seasons and higher temperatures, and more frequent and severe droughts and pest outbreaks are increasing the risk of seasonal production losses.

- Another new thing is the growing recognition that many smallholder farmers are simply not going to succeed as commercial farms in today’s food systems. Some smallholders have opportunities to diversify into more remunerative non-farm activities, and hence may be less interested in commercial farming, while others are constrained from being more successful as farmers by poor access to markets, or because they live in areas with low agricultural potential.

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.