Strengthening Financial Systems for Smallholders

Author(s)

Lead Authors: Panos Varangis, Rong Chen, Toshiaki Ono, International Finance Corporation

Contributing Authors: Hedwig Siewertsen Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa Atsuko Toda Africa Development Ban Rachel Sberro-Kessler The World Bank

Introduction

The demand for financial services among smallholder farmers remains largely unmet in Africa, reflecting the many challenges that both farmers themselves and financial institutions face. Although binding constraints such as high transaction costs and frequent natural disasters and crop diseases still widely exist, important innovations are available, facilitating greater access to financial services. This is mainly due to diffusion of information technology.

This chapter first provides an overview of the demand and supply of financial services for smallholders and the state of the enabling environment, including policies and regulatory frameworks in agriculture and financial sectors. This is followed by recent trends and some notable examples of financial services in credit, investment, savings and payments, and risk management. The delivery mechanism and role of technology are overarching themes which will be described in an independent section. The chapter ends with a set of key takeaways and broad policy framework for consideration

Setting the Stage for an Agricultural Finance System

Demand for agricultural finance

Among 500 million small farms in the world standing on less than 2 hectares each, 41 million exist in Africa, accounting for 80% of all the farms in the continent (Lowder, Skoet, & Raney, 2016). These farms represent a diverse group of agricultural households and farmers which could be categorized differently, using various aspects such as size of landholdings, access to markets, and income levels. Although the size of these farms is small across the board, farmers’ income levels may vary greatly depending on the crops they produce, their market opportunities, and their off-farm income opportunities. This heterogeneity makes the analysis of their demand for financial products difficult.

A Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) publication in 2013 (Christen & Anderson, 2013) provided a systematic segmentation of farmers using their degree of commercialization and ties to value chains (loose versus tight). Since then, there have been various subsequent efforts to refine such segmentation. Among these other efforts, this publication uses the segmentation as discussed in the overview chapter which divides small farms into four categories: subsistence, transitioning, specialized commercial, and diversified commercial.

Although these categories offer a useful framework for financial service providers and policy makers to grasp fnancial requirements of smallholder farmers, the reality is usually much more complex and nuanced. Therefore, a thorough assessment on the demand side is critical for any access of finance analyses and interventions. In addition to national demand surveys, more specific demand surveys usually use questionnaires and farmer focus group discussions. The selection of representative samples often depends on the typology of farmers that is suitable within a country (or project) context and the types of value chains

Supply of agricultural finance

Despite the diverse financial requirements in all the four categories of farmers, both informal and formal financial nstitutions (FIs) in Africa often fail to supply ample and suitable financial services, especially for agricultural production and agribusiness development. In Africa, more than 50% of the population is involved in agricultural activities while less than 1% of banking credit goes to this sector.

The agriculture sector has traditionally been avoided by FIs even when ample liquidity exists in their balance sheets. Despite the presence of abundant business opportunities in agriculture, FIs lean towards lending to other sectors, non-agriculture household needs and/or invest in government securities.

Among various segments in the sector, smallholder farmers are considered among the most difficult clientele to serve in a financially sustainable manner due to various risks and costs involved, including: (1) occasional natural disasters such as drought, flood, and epidemics of crop diseases; (2) high transaction costs due to dispersed rural population; (3) seasonal and lumpy financial requirements, yet limited physical assets for collateral; and (4) a long history of political interventions (both in the agricultural and financial markets) that sometimes create a prohibitive environment for financial services.

Even if the financial services are available, they are often concentrated in cash export-oriented crops and high value chains and wealthier farmers. The costs of the services are generally high, but the variety and quality tend to be limited.

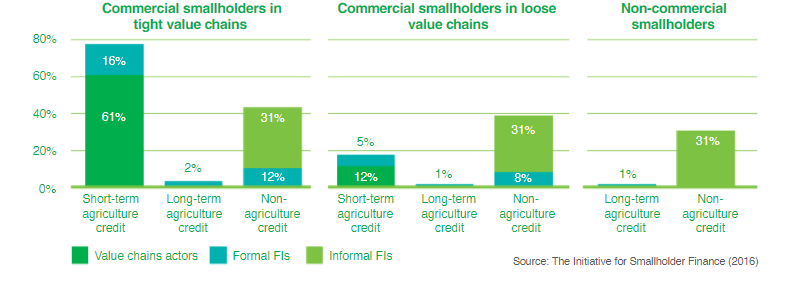

Credit supply from FIs and value chain actors (% of total credit requirements)

Penetration of FIs has also been limited in the provision of other financial services. For example, according to the Global Findex Database, close to 60% of the rural population in sub-Saharan Africa saved some money in the past year, but only 13% saved with formal FIs. The gap between the two represents rural savings requirements served through informal means, including savings groups. Most smallholder farmers do not have bank accounts and transactions are largely conducted by cash.

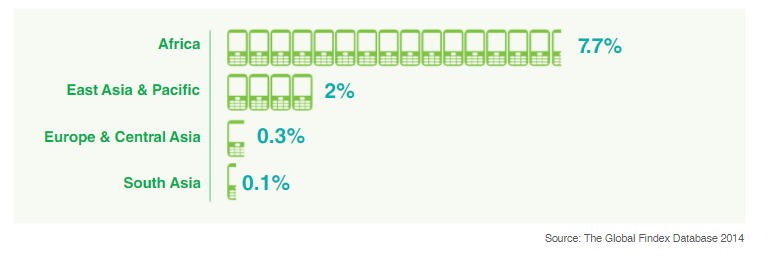

Recent development and diffusion of information and communication technology (ICT) has been quickly changing the agricultural finance landscape in Africa. Rapid penetration of mobile phones and payment services has dramatically increased access to financial services for millions of rural populations. Africa is by far the leading mobile finance market, especially among developing countries backed by high penetration of mobile phones and payment services. For example, traditional cash payments for agricultural products have partially been replaced by mobile payments which reduced the transaction costs and enhanced the security compared to cash transactions.

While most transactions are still conducted in cash, mobile payment is used much more in Africa than in other regions. In addition, some groups of financial service providers including mobile network operators offer mobile-based savings and lending services in some countries; users of these services are increasing rapidly.

Enabling environment: Policies and regulatory framework for agricultural finance

Financial regulations

Financial regulations are rarely established to serve a specific sector. Instead, a full-fledged financial regulatory environment would benefit all the real sectors, including agriculture. Financial regulations facilitate agricultural finance indirectly through various dimensions, including: 1) regulating financial institutions which are important providers of agricultural finance such as local financial institutions including (MFIs), savings and credit cooperatives (SACCOs) and financial cooperatives; 2) establishing standards and guidelines to regulate the current booming digital financial services; and 3) providing a regulatory framework relating to collateral and security interest to facilitate lending.

Financial regulation plays a key role in facilitating the entry of new market participants, lenders, and financial providers in rural markets. SACCOs, MFIs and financial cooperatives, which are more experienced in servicing underserved rural markets (Meyer, 2013) often have risky portfolios with high administrative costs due to managing small agricultural loans (Helms & Reille, 2004). Regulators seek to minimize the credit risk through prudential regulations such as capital adequacy requirements and provisioning rules (Fiebig, 2001).

However, these requirements need to be set at appropriate levels to preclude micro-lenders from entering the market. Additionally, consumer protection regulations with requirements such as transparent interest rate disclosure, compulsory participation in deposit-insurance schemes, and data privacy standards, enhance trust among stakeholders in the financial system. Most of the countries in SSA have established legal frameworks for local financial institutions such as deposit-taking MFIs and financial cooperatives. The West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) adopted the Loi 23 -2009/AN du 14 mai 2009 portant réglementation des systèmes financiers décentralisés (SFDs) in which SFDs are defined as institutions that offer financial services to people who generally lack access to banking services.

Policy Intervention for Agricultural Finance

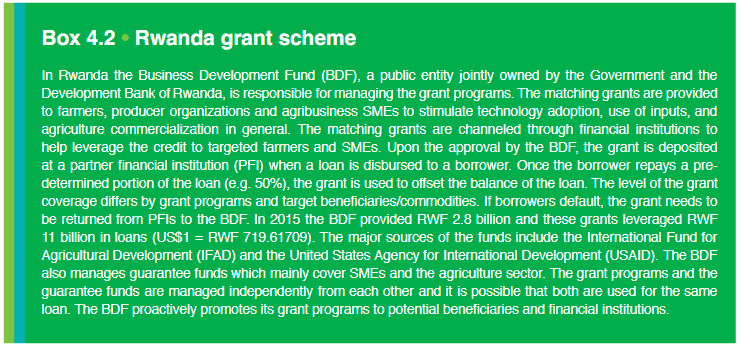

Policy interventions, such as mandatory lending quotas (also referred to as priority sector lending (PSL), interest rate caps, and credit guarantee schemes (CGS), and matching grants, are increasingly used to facilitate lending to the agriculture sector. Trade policies relating to agricultural commodities and subsidy programs on inputs and agricultural equipment also have an indirect impact on agricultural finance. These policies depend on country contexts, and implementation arrangements play a key role in ensuring their effectiveness as policy tools. In Africa, interest rate caps are the more commonly used policy instrument followed by the use of credit guarantees (CGS). Matching grants have also been used in many countries in Africa to promote credit to agriculture, particularly for the longer term, although in most matching grant schemes so far the link to financial markets has been weak.

CGSs share credit risk with their partner financial institutions (PFIs) in exchange for the guaranteed fees. PFIs are expected to lend to pre-defined target borrowers such as smallholder farmers and SME agribusinesses with the guarantees to cover a pre-determined percent of the loan value. A recent World Bank global survey of 60 public CGSs (Calice, 2016) includes 7 African CGSs. Other donor-driven CGSs exist, such as the USAID Development Credit Authority (DCA) guarantee programs and the Private Agricultural Sector Support in Tanzania and Mozambique backed by DANIDA.

Many of these CGSs seem to cover the agriculture sector exclusively or together with other target groups. In Angola, for example, the Fundo de Garantia de Credito issues guarantees to SMEs in all sectors, but 40% of the guarantees issued are in agriculture. Agriculture CGSs tend to suffer from higher non-performing loans (NPLs) and claims than other CGSs. A study of CGSs in Tanzania (Financial Sector Deepening Trust, n.d.) found that the rate of default in CGSs for agriculture was almost always over 10% and as high as 30% whereas that of CGSs for SMEs remained between 5% and 10%. According to an analysis conducted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the claim rate should be lower than 3% for CGSs to be sustainable and successful (FAO, 2013).

The performance of PSL or mandatory lending quotas in facilitating lending to the agriculture sector has been highly variable. Under the PSL, compulsory lending targets are given to lenders, typically banks, to facilitate a higher share of their lending portfolio in priority sectors such as small-scale industries (SMIs) and agriculture. A recent analysis by the World Bank concluded that while some PSL schemes are effective at channeling credit to specific sectors, most of these schemes face a variety of challenges associated with financial inclusion (lack of targeting to the poorest segments, increase in costs of access to credit), declining loan asset quality, and misallocation of limited financial resources.

Among the various models, the indirect model, where lenders lacking the specialized experience in priority sectors are able to purchase certificates from financial institutions that have a comparative advantage in lending to targeted sectors, might help expand access to finance while limiting economic distortions. Policy interventions of PSL mandatory lending quota are not as widely utilized in Africa as in Asian countries such as India, the Philippines and Vietnam. So far, in Africa only Zimbabwe has tried to impose on banks to lend 20% of their portfolio to agriculture.

The financial crisis of 2008 reopened the debate on interest rate controls as a tool for consumer protection. A recent study has found that at least 76 countries around the world currently use some form of interest rate caps on loans (Maimbo, Gallegos, & Alejandra, 2014). The SSA region has the highest number of countries adopting interest rate cap, followed by the LAC region. WAEMU, the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC) and countries, including Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Mauritania, Namibia, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan, and Zambia have adopted interest rate caps.

Recent trends

Short-term creditBoth pre- and post-harvest finance for African smallholder farmers seem to be heavily dependent on the linkages and coordination of the value chain actors. Farmers in tight value chains may have various structures to access credit for their working capital needs given the foreseeable marketing opportunities of the commodities and the payments to be received. For example, FIs provide pre-harvest loans for inputs through collaboration with various value chain actors such as offtakers. Reliable value chain actors and their partner farmers/producer organizations usually provide good entry points for FIs.

In theory, such value chain financing arrangements can supplement lack of sufficient collateral (Miller & Jones, 2010) if FIs could assess the strength of the value chains, the relationships between the actors and transaction flows. However, FIs often miss these important insights and require physical assets as collateral, especially for new borrowers. Offtakers and input suppliers also provide finance directly to farmers based on the track records of business transactions, assuming that the crops will be sold according to the contracts.

In Africa, offtakers are the major source of financing for farmers in higher value and tight value chains. A key risk in value chain finance is the potential of side-selling: the opportunity of farmers to sell to another offtaker to avoid repaying the loan. Tight value chains, where the offtaker monitors the crop and effectively controls the purchases, can reduce this risk considerably.

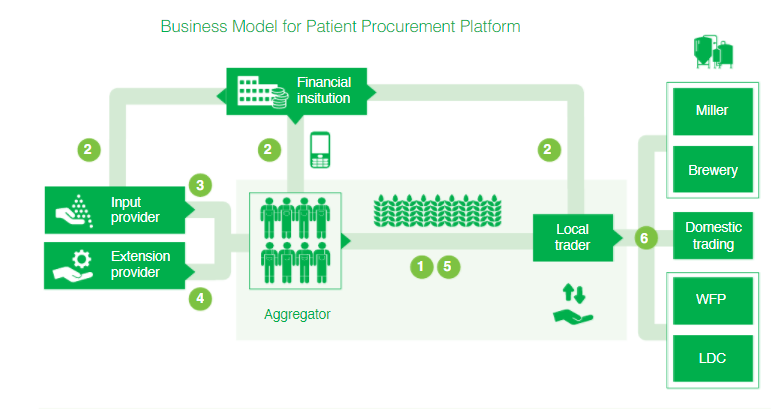

Farm to Market Alliance model

Long-term finance for Investment

Commercial smallholder farmers and producer organizations require longer-term finance for capital investments to grow their operations. Small tractors, processing facilities and warehouses, for example, could improve their productivity and allow them to produce higher-value products. Countries and regions with a single crop cycle could hugely benefit from irrigation facilities. Despite seemingly obvious opportunities, these investment projects often do not happen due to many reasons; one of the binding constraints is lack of long-term finance. In Africa, the demand for long-term finance in agriculture is largely unmet. Although formal FIs such as commercial banks provide investment loans to other sectors, they usually avoid agriculture due to limited physical assets for collateral and inherent risks in the sector. In some African countries alternative funding sources including investment funds and leasing companies exist, some of which serve smallholder farmers.

group of investment funds is currently focusing on African agriculture and agribusiness. A recent FAO study identified 63 agricultural investment funds of which 24 (38% of total) exclusively focus on Africa (FAO, in press). Their investment strategies and target businesses are diverse, ranging from large-scale agro-processors, SMEs, and rural MFIs to producer organizations. Most such investment funds focus on large-scale investment opportunities mainly in lower segments of value chains such as processing and trading that are less exposed to risks in agricultural production.

However, some investment funds, supported by public donors and impact investors, explore investment opportunities in agricultural production and/or agribusiness procuring raw materials from smallholder farmers. Investment funds for producer organizations such as Root Capital, Fairtrade Access Fund (Incofin) and Fair Agriculture Fund (responsAbility) mainly provide debt for trade financing and other working capital requirements. Long-term loans for capital investments are also available. For example, long-term debt accounts for 36% of the portfolio of the Fairtrade Access Fund and while this is one important focus of the fund, it has been the most difficult to finance due to ready-to-finance demand and the risks.

These investment funds for producer organizations deploy US$600 million per year globally and target smaller investments from US$50,000 to 2 million (The Initiative for Smallholder Finance, 2017). However, due to the high transaction costs, small investments are extremely difficult and as a result, less than 10% of their loans in 2013 were below US$300,000 (The Council on Smallholder Agricultural Finance, 2015).

This means that they selectively invest in larger and more established producer organizations. In addition, investments are skewed towards tight value chains where business models are proven and reliable international buyers exist. In Africa, coffee, cocoa, cotton and cashew accounted for close to 60% of their investment portfolio in 2013 (The Initiative for Smallholder Finance, 2014).

Savings and payments

Savings

Saving functions as an effective mechanism to enable long-term financial planning. Given the irregularity of agricultural income, farmers need to save to support on-farm operations—such as the purchase of inputs for the next planting season—or household needs including children’s school fees. Smallholder farmers are often faced with unexpected life events such as birth, marriage, illness, death, and other emergencies. In the absence of viable insurance products, back-up savings can serve as a substitute for insurance, enabling farmers to absorb shocks and cope with emergencies.

Despite the importance of savings for smallholder farmers, several challenges and constraints hinder their ability to save. Financial institutions which provide formal saving options are often beyond their reach. Low returns to savings, and the high transaction costs associated with traveling to bank branches coupled with unreliable transport, impede farmers’ ability to access formal savings products. Where these options exist, products offered by formal financial institutions often require high minimum balances or mandatory deposits. Informal savings mechanisms such as village savings and loans groups (VSLAs) or rotating saving groups (ROSCAs) serve as important mechanisms to enable saving.

However, these informal savings methods are often inadequate or function ineffectively, as households cite the lack of privacy of these savings groups as a key deterrent for participation (Kendall, 2010). Finally, and perhaps most telling, the high level of dependency among rural households is a key constraint in enabling savings. Rural households are often obliged to share their income and savings with relatives and friends, impeding their ability to exercise self-control in accumulating assets and smoothing out consumption.

Payment

Access to payment services is critical to supporting farming operations throughout the value chain. Farmers require access to secure and reliable payment services to facilitate the purchase of necessary inputs, such as seeds and fertilizers. Traders, processors and wholesalers require efficient payment mechanisms to disburse large amounts of money to many contract farmers over a short period of time and to service loan disbursement and repayment. However, most agricultural payments still remain cash-based, which is often expensive and risky, subject to theft, loss, and fraud.

Digital payment offers significant opportunities for key stakeholders, including farmers, mobile money providers, governments and agribusinesses in the agricultural payment ecosystem (GSMA Intelligence, 2016). It provides farmers with a safer and more efficient way to transfer money at lower costs than traditional cash-based transactions. A randomized evaluation in Niger found that using mobile payments for unconditional cash transfers saved recipients 75% on payments (Martin, Harihareswara, Diebold, Kodali, & Averch, 2016). SmartMoney, a savings and payment system currently operating in Tanzania and Uganda, substitutes cash with SmartMoney payments in the entire value chain. Large agribusinesses transfer electronic crop payments through SmartMoney to e-wallets of intermediary buyers, who, in turn, also use the system to pay small farmers. Finally, farmers can spend received digital currency in the numerous SmartMoney shops and with other SmartMoney users in a village (Babcock, 2015).

Risk management

Farmers and agricultural SMEs have various, but often insufficient, ways to manage risks. These include non-financial risk management solutions that reduce production risks (e.g. use of pesticides and irrigation equipment, and diversification); post-harvest-risks (e.g. investment in good quality storage); and market risks (e.g. contracts with buyers, market diversification). In addition, financial solutions can also help farmers and agricultural SMEs deal with the financial impact of risks when these arise. Such solutions include the use of income generating off-farm activities, savings, credit or remittances. This section focuses on agricultural insurance which is a relatively new financial instrument in Africa which can help cope with the financial impact of high-severity low-frequency agricultural risks.

Cost-effective delivery mechanisms and role of technology

The high transaction costs associated with on-site loan appraisal and monitoring of loans along with the opportunity cost in serving low population density markets with poor infrastructure has hindered formal financial institutions from setting up bank branches in rural markets (Höllinger, 2011). In turn, farmers are forced to spend significant amounts of financial resources and time traveling to urban areas to obtain access to basic financial services. In responding to these challenges, branchless banking has emerged as a viable option in delivering financial services outside conventional bank branches (Dias & McKee, 2010). Branchless banking enables users to gain access to basic financial services such as savings and deposit accounts, insurance, payment mechanisms, and credit without traveling long distances.

Agent banking—a model of delivering financial services through partnership with a retail agent (or correspondent) in locations for which bank branches would be uneconomical (Dias & McKee, 2010)—provides cost-effective solutions to promote agricultural financing from both the supply and demand sides. On the supply side, it lowers the cost to banks in establishing physical banking infrastructure to unbanked areas. For instance, the set up costs of a retail agent in Brazil can be as little as 0.5% of the cost of setting up a bank branch (Lyman, Ivatury, & Staschen, 2006). On the demand side, branchless banking provides farmers with more economical options for gaining access to financial services as they do not need to spend out of pocket to reach a bank branch (Jayanty, 2012). According to the Central Bank of Kenya, agent banking was launched in 2011 and by March 2013, a total of 11 commercial banks had contracted 18,082 active agents and were facilitating over 48.4 million transactions valued at US$3 billion (iVeri, 2014).

However, the regulatory endeavors have not caught up with the rapid rate of development agent banking activities in SSA. Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, and Tanzania are among the few countries that have dedicated legal frameworks on agent banking. Among the countries with regulation on agent banking, only Ethiopia allows agents to enter into both exclusive and non-exclusive contracts with financial institutions to provide services on their behalf.

ther innovative technologies, such as distributed ledger technology (DLT), otherwise known as blockchain, have the potential to promote access to financial services for smallholder farmers and agribusinesses. Originally conceived as the backbone of the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, the blockchain is a digital shared record of events, organized into “blocks” and distributed across a network of computers. DLT could be used to record ownership and transfer of property in countries where land title registries are non-existent or poorly maintained, which in turn could allow smallholders to access financing using their land as collateral. The technology could also be applied to collateral registries, in which ownership of even moveable collateral like livestock could be recorded and verified by financial institutions.

Additional applications include insurance policies with automated payouts triggered by smart contracts that monitor weather or sensor data, digital WRS,15 traceability of commodities along the value chain, and receivables financing. However, blockchain technology is still in its infancy (particularly when it comes to agriculture finance applications), and more research is needed to understand its potential application

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.