A Policy Agenda for Achieving an Inclusive Transformation of Africa’s Agri-food Systems

Author(s)

Adesoji Adelaja (Michigan State University), Joseph Rusike (Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa), John Ulimwengu IFPRI, Mabel Hungwe (BEAT Africa), Steven Haggblade (Michigan State University), John Herbert Ainembabazi (Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa), Franklin Simtowe (CIMMYT)

Introduction

Achieving a green revolution by increasing the yields of staple food crops through technology adoption, and institutional, market and policy innovations, is necessary to resolve the first generation problem of accelerating the rate of agricultural growth (Mellor, 1990; Lipton, 2012; de Janvry, 2017). But this is not a sufficient condition to lift large numbers of rural households out of poverty. Reducing rural poverty across the board requires more than a green revolution. It also needs an agricultural and rural transformation. Agricultural transformation allows households to diversify their production systems, smooth out labor calendars over the year, engage in more profitable enterprises, reduce idleness in labor calendars, and improve their diets.

A rural transformation allows the emergence of local, town-based, rural non-farm industries and services that are driven by agriculture. These offer complementary sources of incomes to rural populations.

Achieving a convergence of a green revolution and an agricultural transformation and a rural transformation to lift large numbers of rural populations out of poverty over a few decades has proved elusive in the past. Despite many past attempts, few African countries have achieved a successful smallholder-led green revolution. Successes include maize in Kenya, Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe; cassava in Nigeria, Ghana, Zambia and Malawi; cotton in Mali; horticulture in Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire; dairy in Kenya, Uganda and Ethiopia; and rice and cotton in Mali (Nweke, Spencer, & Lynam, 2002; Haggblade & Hazell, 2010). However, the challenge today is not just that of governments doing now what they have not been able to do before.

The kind of agricultural and rural transformation required today has also changed thanks to the rapid pace of technological change in frontier technologies; globalization; urbanization; digitization; democratization; decentralization; high population growth rate, and an increase in the number of youths as a proportion of the population annually entering the job market; climate change; and extreme weather events. Consequently, new approaches are required. For example, many new opportunities now exist for smallholders to exploit their comparative advantage in labor-intensive farming to grow high-value products for urban markets.

There are many new private sector opportunities for adding value and jobs along value chains. At the same time, value chains are changing in ways that threaten to exclude many smallholders. Climate change also poses new threats that require greater attention to resilience.

Why Did Past Attempts at an African Green Revolution Fail?

The Green Revolution that was launched in the 1960s helped transform Asia from a continent of hunger and despair to a regional success story within 25 years (Rosegrant & Hazell, 2000). That revolution was built on a game changing technology package, but less widely recognized is that it also depended on game changing policies—policies that provided smallholder farmers with the package of modern inputs and credit they needed to adopt the new technology, and an assured market and stable, remunerative prices.

Yet attempts to bring the same type of policy and technology package to Africa largely failed, despite tens of billions of dollars of investment during the 1970s and 1980s. In many ways this has been more of a policy failure than a technology failure, because many proven technologies have long been available in Africa that can substantially raise productivity. However, the technologies have either not been accessible or have been unprofitable to farmers under the prevailing policy environments.

Why did these past attempts fail? The “maize revolution” is a good example of what went wrong. In the 1980s, a major revolution of smallholder maize production occurred in Southern African countries and in the East African highlands. Spurred by the development of appropriate high yielding maize varieties in Zimbabwe (SR 52) and the provision of subsidized fertilizers, subsidized credit, price guarantees and market price support, the new crop varieties spread rapidly—first on large farms and then later on small farms. The maize revolution brought about rapid adoption of improved varieties and fertilizers and rapid growth in yields on smallholder farms; and several of the countries achieved surplus maize production. Malawi, Zimbabwe and Zambia became major maize exporters. Development experts drew parallels with the Asia Green Revolution for rice and wheat calling it the “emerging green revolution for Africa” (Byerlee & Eicher, 1997; Smale & Jayne, 2010)

This success collapsed with the structural adjustment programs (SAPs) that began in the mid-1980s. Partly because of the high budgetary costs of their agricultural programs, governments fell into debt and macroeconomic imbalances and had to turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank for support (Lele, 1989). The agricultural reforms that were part of the SAPs called for liberalization of markets, privatization of parastatals, drastic reduction in public expenditures on agricultural research, extension, and support systems for farmers; elimination of input and credit subsidies; and removal of price support systems (Kherallah, Delgado, Gabre-Madhin, Minot, & Johnson, 2002).

A second attempt to develop maize came from the Sasakawa Global 2000 (SG 2000) efforts in the 1990s. This was based on the assumption that if farmers could be shown the benefits of new varieties and fertilizers, African countries would see a quantum jump in cereal yields and food production.

However, because the effort did not consider the development of markets, rapid growth in production led to price collapses across the countries. As the price of grains fell, farmers quickly abandoned the use of improved varieties and fertilizers. The approach had failed to consider several factors: development of input and output markets; and support of market institutions to assure farmers of markets and better price incentives.

A third attempt to develop maize was undertaken by the Millennium Village projects implemented by the Earth Institute at Columbia University, the United Nations Development Programme, and Millennium Promise to achieve the Millennium Development Goals in 10 countries in sub-Saharan Africa: Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania and Uganda.

This integrated rural development model provided free seeds and fertilizers for farmers; demonstration of new technologies; focused on village level interventions; and expansion of efforts into integrated rural development, including focusing on health, nutrition and education (Nziguheba et al., 2010). Farmers rapidly adopted the improved crop varieties across the Millennium villages, and crop yields rose significantly, sometimes by as much as 400%. Rural health and school attendance improved. But the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) model faced the difficulty of going to scale beyond the pilot villages.

Free distribution of inputs was not sustainable and undermined the development of markets. It was again a “technology-driven model” and it did not pay attention to the development of policies and institutions that will support sustained incentives for the adoption of the improved technologies.

Three major lessons can be drawn from the earlier experiences to trigger a green revolution in Africa:

Technologies can open up greater space for productivity gains in African agriculture. But technologies alone are not enough. To avoid the lesson of “boom and bust” that plagued earlier efforts towards a green revolution in Africa, technical interventions need to be complemented by policies that promote the adoption of green revolution technologies.

It is important to avoid “pendulum approaches” for the green revolution. Neither the public sector nor the market can do it alone; complementary public and private sector investments are also needed. In particular, public policies that improve incentives for the uptake of new technologies need to also simultaneously build markets.

Because of structural poverty traps, many smallholders will need subsidies so they can afford the higher expenditure needed to invest in new green revolution technologies. The challenges here include: how to do this right; how to ensure that subsidies are well-targeted to farmers who need them most; how to reduce elite capture; how to implement “smart subsidies” that directs support to the poor while building markets; how to complement with supportive infrastructure so that subsidies have greater impacts; and how to develop reasonable exit strategies.

What Can We Learn From Past Successes?

National Commodity Example—Tea and Horticulture in Kenya

Kenya has been successful in gaining global prominence in tea production. In 2017, Kenya ranked third in the world in tea production, and 90% of the tea produced was on farms less than one acre in size. Kenya’s success can be attributed to (Kidane, Maetz, & Dardel, 2006): (a) a land redistribution policy adopted at independence which subdivided large holdings and reallocated subdivisions to peasant farmers; (b) institutional support through the establishment of the Kenya Tea Development Authority (KTDA); (c) institution of favorable investment policies; (d) implementation of targeted extension services which involved insights from farmers; and (e) an institutional framework which took advantage of favorable international prices of tea. Since the early 1960s, tea productivity, incomes and export earnings have grown tremendously.

The success in horticulture has been attributed partly to the establishment of the Kenya Horticultural Crop Development Authority (HCDA), which focused on advisory and regulatory support, institutional and marketing arrangements, and advisory services to farmers. According to Kidane et al. (2006), Kenya’s international success in tea and horticulture can be attributed to: (a) a legal and policy framework (land reform, regulatory frameworks and contractual arrangements); (b) institutional support (publically funded authorities and their leadership roles); and (c) provision of public infrastructure.

Africa-wide Commodity Example—Cassava Crop Protection and Market Development

Cassava is a major element of the diet of many Africans. Its production was threatened in the early 1970s by the cassava mealy bug and the cassava green mite infestations (Gabre-Madhin & Haggblade, 2004). The solution to these problems came from the international research community. Research institutions such as the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT) and the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), working in collaboration with multilateral aid agencies like the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), quickly developed and propagated solutions. This effort has been credited for saving African cassava.

Having saved cassava, several nations have built on this foundation to expand cassava utilization. For example, in Nigeria, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) worked with food processors from the bakery sector to promote the substitution of cassava for wheat (an imported commodity) in bread production.

In the process, it facilitated capacity building for cassava related associations, all of which have become partners in the improvement of services to farmers, processors and input suppliers and in the incorporation of cassava into several value chains. While evidence of market success of cassava bread is unclear, the following key lessons were learnt from the cassava effort: (a) research can be effective in solving major problems; (b) research collaboration is essential to successful research based interventions; and (c) a strong connection between research and outreach is important in solving problems.

Program Example—Farmer Education in Nigeria

Credit supply from FIs and value chain actors (% of total credit requirements)

A major problem faced in raising agricultural productivity in Africa is the low level of literacy among rural farmers. Adult education might help correct this problem. Nigeria therefore decided to experiment with an agricultural messaging-based adult literacy program, whereby adult female farmers were assisted to access and interpret information to enhance their productivity.

After two decades, the program has had a measurable impact on productivity and on women’s organization, including the creation of Women in Agriculture (WIA). A study by Okpachu, Okpachu and Obijesi (2014) to determine the impact of adult education on the productivity of small-scale female maize farmers in the Potiskum Local Government Area of Yobe State in Nigeria compared the outputs and incomes of female maize farmers participating in the program to those of non-participants. Regression results show that education significantly affects the agricultural productivity of small-scale female maize farmers. The study recommended that female farmers should participate in adult education schemes and that incentives and government agricultural policies should work in tandem in advancing women success

What Must Governments do Today to Transform Africa’s Food Systems?

First, government must provide an enabling business environment for farming and agribusiness. This is achieved through putting in place favorable macroeconomic policies including better government budget appropriations, deployment and timely release of funds; taxation; ination control; monetary growth; exchange rates; interest rates; price intervention in agricultural inputs and output markets; and intraregional and international trade.

Second, governments also need to put in place the institutional and legal foundations governing the development and growth of efficient and effective farmer organizations; land and natural resources tenure; agricultural input (seed and fertilizer) supply; agricultural finance and insurance; agricultural machinery and farm equipment supply; agricultural output marketing; agroprocessing and small and medium-scale rural industries; and intraregional and international trade.

Third, government needs to complement policy reforms by carrying out institutional reforms in agricultural research and technology development, agricultural extension, agricultural training and higher education, agricultural technical services delivery systems, and multisectoral agricultural planning, coordination and mutual accountability.

Fourth, governments need to invest in rural infrastructure. This includes sanitation, water supply and irrigation systems, farm to market roads, railways, airports, marketplaces, storage facilities, information and communication technolo-gies (ICT), energy, and rural electrification.

What Will it Take to Make it Happen?

Conclusion and Recommendations

Africa needs an agricultural revolution today both as an engine of growth for its agricultural and rural transformation, to meet its future food needs, and to reduce poverty. To achieve it, African governments will need to take smallholder agriculture more seriously, and embark on a development agenda that is focused less on the standard green revolution paradigm of the past and more on developing an “inclusive ood system that can meet the growing demands of increasing urban and middle class populations for a diverse range of fresh, processed and pre-cooked foods.

To achieve this agenda, governments will need to pursue a five-pronged agricultural development strategy. They must provide fundamentals in the form of an enabling business environment for farming and agribusiness; invest in adequate levels of basic public goods like research and development, extension, and rural infrastructure; undertake targeted interventions to help commercialize many more smallholders and promote the development of SMEs along food chains; and they must maintain adequate safety nets and social protection programs for the rural poor.

Implementing the agenda will be a challenge; few governments seem able to marshal the levels of support needed for successful agricultural transformation. Smallholders have a limited voice in the political arena, and few political leaders seem ready to prioritize agriculture when it comes to resource allocation. Bolder political action will be necessary. Another challenge is weak public sector capabilities to design and implement a coherent program of policies and investments, or to partner effectively with the private sector and other key players in the food system. Within this context, the comprehensive agriculture sector-wide strategies favored by development agencies and planning departments have limited impact.

They attempt to do too many things at the same time without considering the weak capabilities of many public institutions, the prevailing financial constraints, the long gestation periods required for some investments, or the political time frame available to produce successful results before governments change or lose interest.

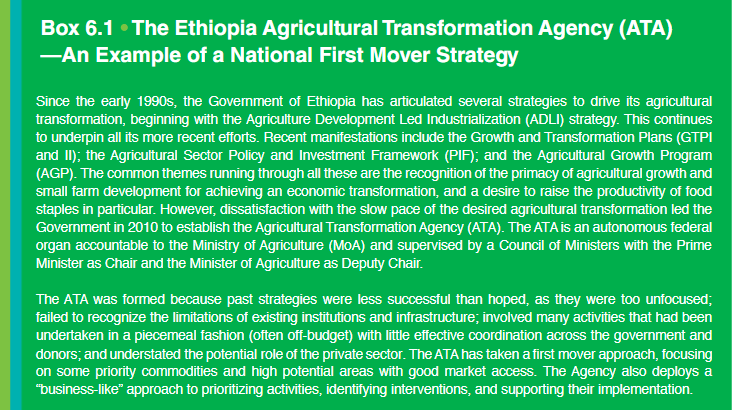

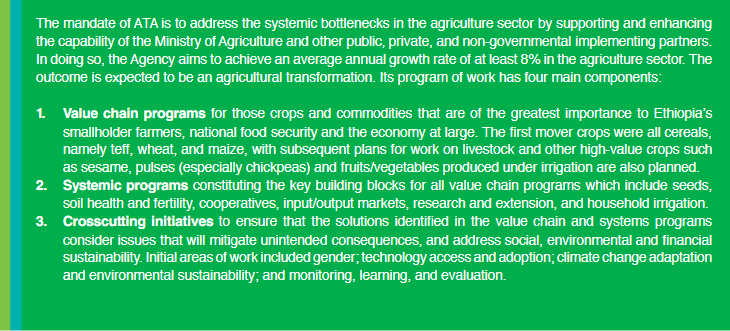

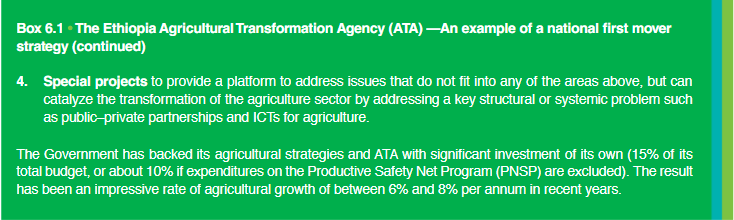

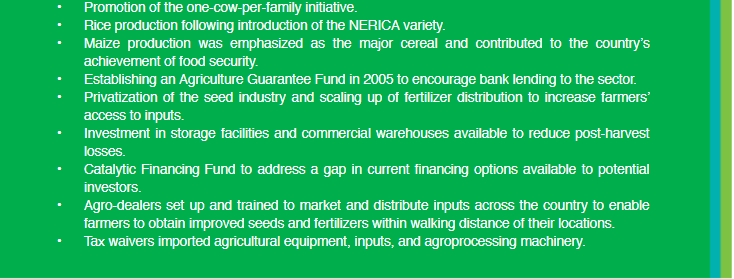

A more practical approach is for governments to concentrate on a few first movers, which may be priority commodities or regions, and to drive these for early successes in terms of growth and employment. Establishing quick success helps build momentum and political support for further agricultural investments. It also opens up new growth opportunities elsewhere in the sector.

Several first mover approaches are being tried in Africa, ranging from national agricultural transformation agendas in Ethiopia and Nigeria which prioritize specific commodities and regions; to the targeted development of specific value chains in many countries; to spatial initiatives like agro-corridors, agro-clusters, agro-industrial parks, and agro-based SEZ. These approaches provide platforms that enable relevant public and private sector players to come together to better serve groups of smallholder farmers, while enabling public and private investments in infrastructure and supporting services to achieve critical levels

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.