Author (s)

Yuan Zhou, Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture

Overview of Agricultural Mechanization in West Africa

Farm power in West Africa relies to an overwhelming extent on human muscle, based on operations that depend on the hoe and other hand tools. Such tools have implicit limitations in terms of energy and operational output, particularly in a tropical environment. These methods place severe limitations on the amount of land that can be cultivated per family. They reduce the timeliness of farm operations and limit the efficacy of essential activities such as cultivation and weeding, thereby reducing crop yields.

Types of Agricultural Machinery in Use

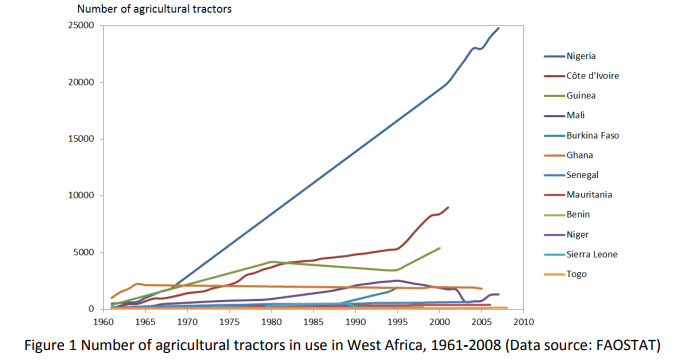

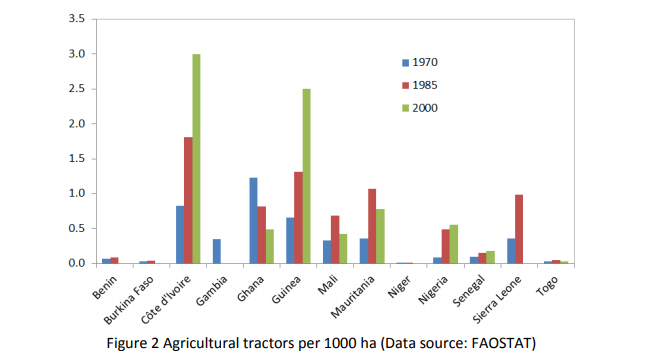

The most commonly used agricultural machinery includes tractors, combine harvester, thresher, manure spreader and fertilizer distributor, plow and cultivating machines, seeder and planters. Figure 1 shows the evolution of agricultural tractors in use in West Africa. Nigeria leads in the total volume, followed by Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea. If we look at tractor usage per hectare, a different pattern emerges (Figure 2). In 2000, Côte d’Ivoire led the field, with about three tractors per 1000 hectares, followed by Guinea. All the other countries had less than one tractor per 1000 ha. It is worth noting that while most countries had increased the level of mechanization over time, Ghana was the reverse. The data for most recent years are unavailable from FAO, however.

More recent country reports show that in Mali in 2010 there were 1,114 threshing machines, 703 mills, 1,286 huskers, 3,878 motor-pumps, 520 multifunctional platforms and 9 mini rice mills (Direction Nationale du Génie Rural in Side, 2013). In Burkina Faso, about 40% of farmers were mechanized in 2006, largely with draught animals (Side, 2013). There were about 8621 tractors in the country, used on 0.4% of the farms

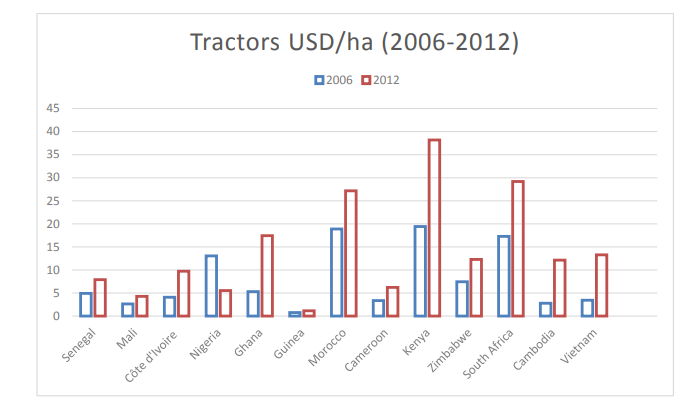

How does West Africa compare with other countries in Africa or Asia? Drawing on the UN Comtrade data, we compared the use of “tractors” across countries. Kenya, South Africa and Morocco are the leaders in tractor investment in 2012, far higher than countries in West Africa. Two small Asian nations, Cambodia and Vietnam are at comparable levels with Ghana and Nigeria.

If we look at regional averages, we find that Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has the lowest percentage of engine power in total power for land preparation (Table 2). East Asia fares only slightly better with 20%; but the percentage of draught animal power is much higher than in SSA. As in Africa, farms in East Asia are predominantly small, which limits the use of mechanization. Latin America has the highest level of mechanization in the developing world.

Different Models of Machinery Usage

There are several different models of equipment usage, including individual ownership and usage, collective ownership, fee-based service delivery and renting/leasing. For large landowners who can afford it, individual ownership is the obvious choice. The other models are discussed below.

Collective ownership

Joint use of machinery, especially for soil preparation or cultivation, is possible through farmer organizations or structured cooperatives. A case in point is the Farm Machinery Cooperative in Benin. Most farmers there cannot afford to purchase machinery individually, so shared ownership is one of their few options. Modelled after the French system of the Coopérative d’utilisation de matérial agricole (CUMA), the first cooperative system for the purchase and use of agricultural machinery was built in Benin in 1997. Since then, about 120 CUMA organizations have been established across the country, with around 1,200 members (FARM, 2015). CUMA is based on voluntary membership of small farmer groups that wish to invest in machinery. Group members coordinate their farming tasks and exchange skills and best practices. CUMA is based on voluntary membership of small farmer groups that wish to invest in machinery. Group members coordinate their farming tasks and exchange skills and best practices.

However, in Benin, the purchase of mechanization equipment is difficult. Lacking access to credit, farmers save up money within the group, which can take several years. In addition, it is hard to find adequate and affordable machinery. As a result, most CUMA depended on intermediaries such as government funds or NGOs to acquire or import the necessary machinery.

CUMA tractor users predominantly farm cotton and corn. The tractors enable them to time planting better and cultivate about 3.5 times more land than before. The farmers involved specialize their production and focus on the market. With a tractor and plow, only certain tasks in the growing cycle are mechanized, so more manual labor is needed for in planting, weeding and harvesting.

Service delivery models

An alternative to collective ownership is payment for use of a machine and driver for a specific period of time or land area. Such services are usually provided by private companies able to make large upfront investment. Some well-resourced farm cooperatives can offer machinery hire. Pre-harvest services typically include land preparation, sowing, cultivation and harvesting. Post-harvest services include threshing, and crop processing.

An example of sustainable service delivery model is the Center for Mechanized Services (CEMA) developed and tested by the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture since 2014 in the Senegal River Valley in the northern Senegal and in the Office du Niger area in Mali. The model has been established in order to address the issue of timely completion of field preparation and grain harvesting in rice growing systems. Essentially, CEMA aims to aggregate demand of mechanization services from many smallholders and to organize the sustainable supply of such services through large-scale machinery (and thus considerable upfront investment).

These include tractors, combine harvesters and storage facilities. The machines are owned by a farmer union but are managed by a private entity which is responsible for operations, maintenance and financial management in accordance with agreed terms and conditions. A Guarantee Fund was set up to help farmer unions to access bank loans for purchasing agricultural equipment.

Another innovation is “Hello Tractor”, a young Nigerian start-up enterprise that buys tractors and hires them out via an SMS-based hiring and mobile payment scheme (Ströh de Martínez et al., 2016). Hello Tractor equipped some farmers with tractors and established a so-called Smart Tractor network, via which other farmers can hire these. The tractors come with a range of equipment parts which can be used for different crops and production systems. This enables tractor owners to offer service year-round.

Leasing

Before the 1980s, mechanization efforts in many African countries focused on governments importing large tractors and hiring them out in state-run schemes. Despite huge efforts and large sums of aid, this approach proved unsustainable. Spare parts, technicians and fuel were all lacking, causing long downtimes (Ströh de Martínez et al., 2016). In addition, large tractors were inappropriate for smallholders’ plots. Long distances between small farms made state hire schemes unprofitable, with corruption and elite capture aggravating the situation (FAO, 2008). Some of these constraints still apply today, but machinery supply in Africa has become much more diverse. Smaller and cheaper equipment adapted to smallholder agriculture has been imported from Asia and Latin America. This has created new opportunities for the rental services.

Key Issues and Challenges in Mechanization

One of the biggest challenges for successful mechanization in West Africa is access to finance. The cost of tractors and agricultural machinery is far beyond the reach of most farmers. Farmers typically lack collateral for bank loans. This severely holds them back from investing in machinery. Collective ownership can be a solution. However, this requires time for members to accumulate adequate funding, as well as strong cooperative management and training in machinery use.

Another challenge is the availability of well-adapted machines for local production systems. Locally produced machinery is usually low in quality and high in price. Provision of spare parts, advice and other services is often underdeveloped, particularly in remote areas. Adaptation of machinery to current production systems and farmers’ needs is badly needed. The private sector also needs to step up its efforts to provide adequate maintenance and repair services.

Land security poses an additional challenge to mechanization. Many farmers lack land tenure or longterm land use rights. They therefore tend not to invest heavily in their farms, or in preventative measures against degradation (e.g. grubbing, anti-erosion methods). In addition, with little extension support, farmers in West Africa lack the knowledge and skills to operate mechanized equipment. This can lead to misuse and mismanagement of machinery, especially of more sophisticated items.

Major Drivers and Trends in Mechanization

Funding of agricultural mechanization in West Africa remains a major challenge. Existing financial models include leasing, grants, government subsidies, joint ownership, and lease-to-own financing. In “lease-toown”, farmers make regular payments (through a loan or cash) over a set period, and take ownership once the payments are complete. Some models have demonstrated success like CUMA in Benin (albeit still at limited scale), which was replicated in Mali in 2001 and Burkina Faso in 2004. However, where conditions for profitability are missing, failures abound. Successful mechanization depends, for example, on its suitability for the soils, physical geography (e.g. slope) and crops, as well as on the intensity of work, purchasing costs, and functioning of equipment and usage rates.

Another recent trend has been for policy-makers to integrate mechanization as a pillar of broader agricultural policy protecting local production against market risks and providing research and development, training and necessary inputs. In 2010, the Beninese government clearly specifies the development of agricultural mechanization as one of the main components in the Agricultural Investment Plan 2010 – 2015 (MOA, 2010). The objective is to increase the rate of mechanized operations through adaptation of technologies and public-private partnerships. Moreover, an increasing number of development projects focus on mechanization adaptation to local production systems. For example, CIMMYT, together with the Syngenta Foundation is working in Zimbabwe to develop locally adapted machinery prototypes.Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.