Author(s): Ruth Maclean

Affiliated Institution: The Guardian

Type of Publication: Article

Publication Date: 11 September 2017

Redemption Camp has 5,000 houses, roads, rubbish collection, police, supermarkets, banks, a fun fair, a post office even a 25 megawatt power plant. In Nigeria, the line between church and city is rapidly vanishing. “Ha-lleluuuu-jah,” booms the distinctive voice of Pastor Enoch Adeboye, also known as the general overseer.

The sound comes out through thousands of loudspeakers planted in every corner of Redemption Camp. Market shoppers pause their haggling, and worshippers some of whom have been sleeping on mats in this giant auditorium for days stop brushing their teeth to join in the reply. Hallelujah is the theme for this year’s Holy Ghost convention at one of Nigeria’s biggest megachurches, and all week the word echoes among the millions of people attending.

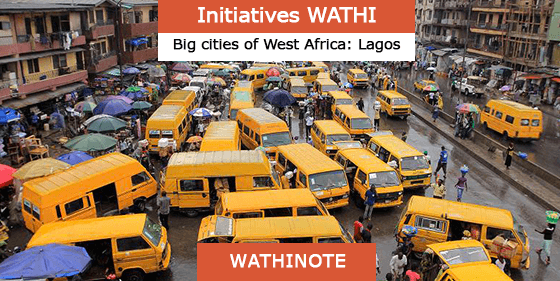

As evening falls on Friday, Adeboye, a church celebrity, is soon to take the stage at his vast new auditorium to give the convention’s last, three-hour sermon. Helicopters land next to the 3 sq km edifice, delivering Nigeria’s rich and powerful to what promises to be the night of the year. Thousands of worshippers surge up the hill towards the gleaming warehouse. Shiny SUVs, shabby Toyota Corollas and packed yellow buses choke the expressway all the way from Lagos, 30 miles away.

But not everyone has to brave the traffic. Many of those making their way to the auditorium now live just around the corner. The Redeemed Christian Church of God’s international headquarters in Ogun state has been transformed from a mere megachurch to an entire neighbourhood, with departments anticipating its members’ every practical as well as spiritual need.

A 25-megawatt power plant with gas piped in from the Nigerian capital serves the 5,000 private homes on site, 500 of them built by the church’s construction company. New housing estates are springing up every few months where thick palm forests grew just a few years ago. Education is provided, from creche to university level. The Redemption Camp health centre has an emergency unit and a maternity ward.

As evening falls on Friday, Adeboye, a church celebrity, is soon to take the stage at his vast new auditorium to give the convention’s last, three-hour sermon

On Holiness Avenue, a branch of Tantaliser’s fast food chain does a brisk trade. There is an on-site post office, a supermarket, a dozen banks, furniture makers and mechanics’ workshops. An aerodrome and a polytechnic are in the works. And in case the children get bored, there is a funfair with a ferris wheel.

The camp is becoming a city

Set up 30 years ago as a base for the church’s annual mass meets, as well as their monthly gatherings, Redemption Camp has become a permanent home for many of its followers. “The camp is becoming a city,” says Olaitan Olubiyi, one of the church’s pastors in whose offices Dove TV, the church television channel, is permanently playing.

Throughout southern Nigeria, the landscape is permeated by Christianity of one kind or another. Billboards showing couples staring lovingly into each other’s eyes, which appear at first glance to be advertising clothes or condoms, turn out to be for a pentecostal church. Taxi drivers play knock-off CDs of their favourite pastor’s sermons on repeat, memorising salient lines.

“If you wait for the government, it won’t get done,” says Olubiyi. So the camp relies on the government for very little it builds its own roads, collects its own rubbish, and organises its own sewerage systems. And being well out of Lagos, like the other megachurches’ camps, means that it has little to do with municipal authorities. Government officials can check that the church is complying with regulations, but they are expected to report to the camp’s relevant office. Sometimes, according to the head of the power plant, the government sends the technicians running its own stations to learn from them.

Haggai, the church’s property developer, is named after the prophet who commanded Jews to build the second temple of Jerusalem. Almost all the houses on Nine have been sold, and Haggai is about to move on to Estate Ten. There is no perimeter wall around Redemption Camp, so it can expand indefinitely.

Mortgages are arranged through Haggai bank, headquartered in Lagos. There has been a knock-on effect on surrounding areas: in some cases, the price of land near Redeemed Camp has increased tenfold over the past decade.

For years, people have owned houses here to stay over after conventions and the monthly services. But increasingly, families like the Oliatans find themselves wanting to live full-time with people who share their values, in a place run by people they feel they can trust. “We feel we’re living in God’s presence all the time. A few days ago, Daddy GO took a prayer walk around here,” Oliatan says.

“If you wait for the government, it won’t get done,” says Olubiyi. So the camp relies on the government for very little it builds its own roads, collects its own rubbish, and organises its own sewerage systems. And being well out of Lagos, like the other megachurches’ camps, means that it has little to do with municipal authorities

Like all the other businesses on site, banks are attracted by the infrastructure and the sheer numbers in attendance it’s like having a stall at a music festival. But the tentacles of the Redeemed Christian Church of God reach much further: it says it has five million members in Nigeria, and more at its branches in 198 other countries. “It’s in virtually every town in Nigeria, and that means some business,” Olubiyi says. “Anywhere you have two million people congregating, banks are interested.”

This also means business for the church, of course. Daddy GO’s private jets don’t appear out of thin air, though there is plenty of cash flowing in from collection plates which these days are often just card machines. Religious institutions are tax-exempt in Nigeria. Redeemed authorities say that its income-generating arms pay tax, but it is hard to say where these end and the church begins. In any case, the church has powerful members, so it would take a brave tax-collector to look deeply into its finances.

In fact, Daddy GO is a former mathematics lecturer, and has clearly not lost his head for figures. He is constantly dreaming up new enterprises including a printing press, hundreds of holiday chalets on the site and a church-owned window manufacturer, which imports the components from China and assembles them to sell or use in camp projects. You can usually tell when Daddy GO is about to appear he is preceded by his personal saxophonist.

Finally, the man who keeps the money coming in, who gives this entire neighbourhood its raison d’être, the de facto mayor of what is effectively an entirely new piece of city, takes his place on the vast stage and picks up the mic. The 75-year-old Daddy GO wears a grass-green short-sleeved suit, bow tie and gold watch. After praying on his knees at the lectern, he climbs to his feet.

“Will somebody shout Hallelujah ?”

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.