Author(s): Tolu Ogunlesi

Affiliated Institution: The Guardian

Type of Publication: Article

Publication Date: 23 February 2016

Makoko is the perfect nightmare for the Lagos government – a slum in full view, spread out beneath the most travelled bridge in west Africa’s megalopolis. Yet this city on stilts, whose residents live under the constant threat of eviction, has much to teach.

“One bucket, one life,” says Ojo, puffing on a marijuana rollup. We have stopped by the Floating School, a two-storey solar-powered wooden structure that floats on the Lagos lagoon on a bed of plastic barrels. I ask him to explain what he means. It’s the young fisherman’s way of summing up the dangerous exertion that is his part-time vocation: sand dredging off the coast of Makoko, the world’s biggest floating city.

The dredgers, he explains, descend a wooden ladder into the depths of the lagoon, armed with only a bucket and the will to live. The depths to which they go mean total submersion. Then they have to climb out with a sand-laden bucket that will be emptied on to the floor of a boat. When the boat is piled high with wet sand high enough so that it’s on the verge of sinking it sails to shore, from where the sand is loaded on to trucks, for delivery to building sites around the city.

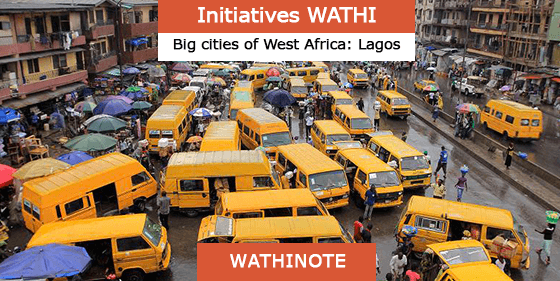

On this, my fourth visit, Makoko is as I’ve always known it: the tiny “jetty” from which visitors and residents board dugout canoes into the labyrinths of the floating settlement; the grey-black sludge that passes for lagoon water; the tangle of boats impatiently slithering through the labyrinth of waterways, making the traffic of Makoko reminiscent of the notorious Lagos roads. Then there’s the hustle and bustle of human activity: women smoking fish or peddling food and bric-a-brac; half-naked children rowing their own boats or playing on the verandas of the wooden shacks; congregants in white garments, singing and dancing in impromptu churches on boats.

Makoko is also the perfect nightmare for the state government a slum in full view, spread out beneath the most travelled bridge in west Africa’s largest city. Everyone who flies into Lagos to do business on the Islands is likely to find themselves passing over the Third Mainland Bridge. For a city keen to recreate itself as forward-looking, Makoko is a dismal advertisement, and the government knows this. It is, therefore, ever keen to pursue the seemingly easiest solution to this “embarrassment”.

An estimated 2,000 people enter Lagos every day, many ending up in informal settlements like Makoko. It was founded as a fishing village in the late 19th century, by immigrants from the Egun ethnic group. As its population swelled and land ran out, they moved on to the water. Today Makoko is home to people from a variety of riverine communities along Nigeria’s coast.

Water world

The area known to outsiders as Makoko is actually six distinct “villages” spread across land and water: Oko Agbon, Adogbo, Migbewhe, Yanshiwhe, Sogunro and Apollo. The first four are the floating communities, known as “Makoko on water”; the rest are based on land. The appellation used for the collective, by the Lagos State Government and NGOs, is Makoko-Iwaya Waterfront. But both sides are united by the water, upon which they depend for livelihood, as well as the Yoruba language, which serves as a lingua franca in a settlement where multiple languages are spoken: French, English, Yoruba and Egun.

From the Third Mainland Bridge the fastest route from the island “downtown” to the airport Makoko looks serene. Wooden shacks stand on stilts, as boats named Bejamin, Gbenon Nu or Ahude glide across the still water. Amid the evening rush-hour traffic on the bridge, Makoko basks in the dull orange light of the setting sun, a soothingly familiar presence.

Makoko is also the perfect nightmare for the state government a slum in full view, spread out beneath the most travelled bridge in west Africa’s largest city. Everyone who flies into Lagos to do business on the Islands is likely to find themselves passing over the Third Mainland Bridge

Close-up, though, it throbs with the kind of energy that marks Lagos out and has made it a darling of urban theorists. Makoko shares with Lagos the exceptional situational inventiveness that makes the entire city tick. Take the matter of clean drinking water: criss-crossing the lagoon bed are pipes, paid for and laid by enterprising residents to bring in clean water for a modest fee from boreholes in neighbouring Sogunro. The population estimates vary widely, from 40,000 to as much as 300,000. “Nobody knows, there’s no [credible] data available,” says Monika Umunna, of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, one of the most active non-governmental organisations at work in Makoko.

Presiding over various parts of the waterfront are local chiefs, known as Baales. One of them is Emmanuel Shemede, crowned in 2005 as the Baale of Adogbo Village. His territory contains the only two primary schools: Whanyinna Nursery and Primary School, founded in 2008 by his younger brother Noah; and the floating school, which has generated more positive buzz for Makoko than any other thing in recent years.

Baale Shemede’s house is built from wooden planks, and rises, like every other structure here, on stilts out of the brackish water. On the ground floor are two sections: one his living quarters, the other a Baptist church that he gifted to a missionary friend. The Baale wants to know why we are visiting. His voice carries a hint of guardedness, which is not surprising to me.

There’s a widespread feeling that many of the people who come to Makoko to take photographs do so to make money off it selling photos or stories to raise funds from which the people of Makoko will never benefit. Some of the wariness is also self-protective: the community has had to face up to government officials displeased by the embarrassment they believe photographs from Makoko attract.

Resistance

This embarassment is what spurs demolitions like the one in 2012. In the last few years, Lagos state has seen several. Badia, a swampland settlement on the edge of the city’s Apapa Port, was one of the worst-hit targets. More than 15,000 people have lost their homes.

“The idea that the government can simply push people from their homes, with no discussion, no recognition of decades of residency … seems unfortunately normal in Lagos,” says Robert Neuwirth, who lives in and writes about informal settlements like Makoko around the world. “The authorities in Lagos seem to approach city planning from an authoritarian point of view as if their desire for development transcends everything.”

A real community

There are three possible options for Makoko’s future. First is that it goes the way of Badia East, razed for high-rises, or Bar Beach, site of a massive land reclamation project that is turning nine square kilometres of Atlantic Ocean into what developers are touting as “the Manhattan of west Africa”, a residential and commercial mini-city called Eko Atlantic. Lagos is starved of land but has no shortage of property developers; were Makoko to sink (or be crushed), in its place would rise apartment blocks and villas priced out of the reach of all but the wealthiest Lagosians.

Second is that the government will stop obsessing with demolition and focus instead on providing the infrastructure that citizens expect of their administrators hospitals, schools, electricity and allow Makoko to develop in its own way and at its own pace, as Neuwirth recommends.

There’s a widespread feeling that many of the people who come to Makoko to take photographs do so to make money off it selling photos or stories to raise funds from which the people of Makoko will never benefit. Some of the wariness is also self-protective: the community has had to face up to government officials displeased by the embarrassment they believe photographs from Makoko attract

Third is a middle road of sorts: the implementation of the regeneration plan, a collaborative compromise between residents, civil society groups and government. The floating school may have acted as a catalyst here: built using local labour, with financial support from the UNDP, it was nominated for the Design Museum’s Design of the Year Award and has become Makoko’s most famous and popular building. “The floating school has been adopted by the Lagos State government as a model that’ll be used for developing the houses on water in the community,” says Oshodi. In 2013, Kunlé Adeyemi, who designed the school, told me: “Eko Atlantic is about fighting the water; [here in Makoko] we’re saying live in the water!”

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.