Les auteurs

Fondé en 2007, L’Institut de recherche sur l’Afrique (ARI) est une organisation indépendante et non-partisane. Il encourage le débat, interroge l’orthodoxie et défie la «sagesse reçue» dans et autour de l’Afrique. L’institut attire l’attention sur les bonnes pratiques et l’innovation, tout en identifiant les nouvelles approches qui pourraient être nécessaires sur le continent. La recherche d’ARI est largement diffusée en Afrique et ailleurs auprès des décideurs, des institutions et des individus qui s’intéressent vivement à l’avenir du continent. La transcription de cette interview a été réalisée par les chercheurs Jamie Hitchen et Edward Paice.

Lien vers le document original ici.

La question du contrôle de l’utilisation des ressources publiques est une problématique centrale de développement en Afrique. Il est important de comprendre le rôle capital joué par les organes de contrôle des finances publiques, leurs mécanismes de fonctionnement, ainsi que les liens qu’ils entretiennent avec les Etats.

WATHI a porté son choix sur cet entretien car elle permet aux citoyens des pays de la région de connaître le rôle des institutions comme l’Auditeur général et son équivalent dans les pays francophones, rôle qui est crucial a priori pour lutter contre la corruption, le détournement des ressources publiques, leur mauvaise utilisation et l’impunité qui encourage ces maux. Cet entretien est un témoignage d’une personne qui est en fonction et qui expose clairement les contraintes et les limites à l’action de telles institutions.

Dans le rapport, trois champs d’action devraient faire l’objet d’attention spéciale pour les pays de la région en ce qui concerne le contrôle des finances publiques.

Par rapport au système sur lequel sont fondés les audits, il est important que les organes d’audits soient indépendants financièrement de l’Etat. Cette indépendance doit être garantie par l’autonomie du budget assurant leur fonctionnement et la réalisation de leurs activités.

Le système de contrôle des organes est basé sur des recommandations qui ne sont pas mise en œuvre. En effet, la plus grande limite de ces institutions est que leurs rapports n’ont pas souvent de conséquences même lorsqu’ils soulignent des faits graves de mauvaise gestion des ressources publiques. Par exemple, entre 2010 et 2014, l’Auditeur général de la Sierra Léone a présenté 953 recommandations, dont 231 ont été appliquées, 75 sont en cours et 647 n’ont pas été suivies d’effet.

Il serait opportun de prévoir des mécanismes de contrôle et de suivi de l’application de ces recommandations. Ces mécanismes pourraient avoir un caractère contraignant qui obligerait les audités à rectifier et à se conformer aux lignes directrices dégagées dans les rapports d’audits. Il pourrait s’agir, par exemple, de ne pas octroyer le reste du budget tant que certaines recommandations au moins ne sont mises en pratique. Il est important que les recommandations soient suivies de façon effective.

L’Auditeur général n’a véritablement pas de pouvoirs coercitifs. Son mandat se limite à rendre compte des résultats de l’audit au parlement. Dans ce sens, il faudrait augmenter le pouvoir des parlementaires en matière de contrôle d’audit et de répression en leur garantissant une indépendance absolue.

Les Etats doivent mettre davantage l’accent sur la répression des actes soulignés dans les rapports. Les malversations financières mises en exergue doivent faire l’objet de poursuite par les institutions appropriées. La solution serait, par exemple, d’obliger les auteurs à recouvrer l’argent en procédant aux remboursements. Cette répression implique aussi l’élargissement des pouvoirs des contrôleurs dans la prévention même de ces délits par le contrôle des fonds injectés, y compris dans les projets de développement internationaux.

Les organes de contrôle pourraient asseoir leur légitimité en rendant plus accessibles leurs rapports. Pour cela, il faudrait d’avantage impliquer les organisations citoyennes qui pourraient demander des comptes aux dirigeants et obtenir des suites des rapports des organes de contrôle comme l’auditeur général, les Inspections des Finances, les Cours des comptes, le Vérificateur général.

Extraits choisis du document

Les extraits suivants proviennent des pages : 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 1O

Since her appointment in 2011 as Auditor General of the Republic of Sierra Leone, Lara Taylor-Pearce has put forward 953 recommendations for improving public financial management. Government action on recommended reforms has been partial and invariably slow, but the profile of the Audit Service Sierra Leone (ASSL) continues to grow. While striving to encourage greater transparency, efficiency and accountability in government, Taylor-Pearce is equally keen to raise public awareness of the critical importance of sound governance.

In this interview with Jamie Hitchen, policy researcher at Africa Research Institute, Taylor-Pearce reflects on the institutional development of the ASSL. Maintaining its independence is “a daily struggle”, but one she considers worth pursuing if it leads to closer scrutiny of the management of public funds in Sierra Leone.

Exposing anomalies and discrepancies in the use of public funds can have consequences for the fiscal and operational independence of audit offices. In Tanzania, where the National Audit Office’s annual and special reports have revealed the loss of billions of shillings in central and local governments, as well as state-owned enterprises, the government proposed reducing the office’s budget by 50% in May 2016. Widespread public opposition eventually prompted a reversal of the decision, but the incident highlighted that audit offices often depend financially on the governments they are scrutinizing. Another limitation audit bodies throughout the continent share concerns follow-up of their findings and implementation of recommendations by the appropriate authorities, including parliamentary public accounts committees, anti-corruption commissions and the offices of attorneys general.

In Sierra Leone, less than one-quarter of the audit office’s recommendations have been enacted in the past five years and no individual prosecutions for malfeasance have been brought. Kimi Makwetu has decried this situation in South Africa: “our system [is based on] recommendation, which relies on the next person to act. And if they do not wish to act it is effectively back to square one”.

Of course, in countries where corruption in government is endemic and systemic, the findings of audit offices can be used expediently – to get rid of political rivals or present the “right image” to donors. But there is reason for optimism, especially if citizens, in increasing numbers, mobilise as a result of being better informed as is their right in constitutional democracies.

Initiatives such as BudgIT8 in Nigeria have shown that there is a growing appetite for public scrutiny of state expenditure when the figures are communicated in a simplified and engaging way. If audit offices are able to “co-opt” or at least engage more closely with the public, while maintaining their autonomy and credibility, they are likely to have an even greater role in fostering transparent and accountable governance.

An independent auditor

Are the reports and recommendations of the Audit Service Sierra Leone (ASSL) heeded by the government and acted upon in the way you would like? Do you have adequate resources for your work?

ASSL is mandated to report findings to the nation’s Parliament, as is the case for many other supreme audit institutions around the world. It is up to parliamentarians to scrutinise the report and ask the auditees to address the concerns raised. Between 2010 and 2014, this office put forward 953 recommendations, of which 231 were implemented, 75 are in progress and 647 were not implemented. For the whole public financial management system to be more effective, and for the people of Sierra Leone to benefit in full from funds generated by the government or received from international partners, it is important that audit recommendations are acted upon better.L’objectif est de prévenir, notamment, les conséquences négatives des réformes en réduisant les risques de corruption.

In Africa auditing can be a risky business because the work often exposes what people want to hide. Public sector auditors need to be well remunerated. It is important for audit offices to establish and retain fiscal independence. Doing our job and maintaining our independence is a daily struggle. Tensions exist between supreme audit institutions and governments across the world. Governments are mandated to pay the salaries of audit staff but are often criticised by report findings.Il s’agit là d’une préoccupation majeure qui est d’actualité dans notre pays, au moment où l’Acte III de la décentralisation et le Plan Sénégal émergent (PSE) sont en cours d’exécution.

On public financial management

The ASSL website states that “through independent professional standards-driven audits we establish to a level of audit assurance that public moneys are used by the government in the manner intended by parliament”. What would be your overall assessment of the government’s use of funds in terms of value for money and accounting for expenditure? What improvements in public financial management have you seen since your appointment as Auditor General in 2011?

In 2013, 44.4% were audited as unqualified or satisfactory. That number has risen to 72.2%. An unqualified opinion is an independent auditor’s judgement that a company’s financial records and statements are fairly and appropriately presented. However, there are still lots of areas where change is needed.

Take procurement as an example, because that is where the money is and that is where unethical activities tend to occur. The rules set out in the Public Procurement Act of 2004 are still frequently flouted.

Every year we audit ministries of “high importance” – broadly based on the funding they receive – alongside other specially selected MDAs (ministries, departments and agencies). Quality is equally, if not more, important.

The outbreak of Ebola showed up the health sector as a shameful panoply of dysfunction. In 2014, payment was made to a contractor to supply ambulances during the Ebola crisis. I have seen no evidence of that contract being fulfilled in its entirety. Budget padding inflating the price of goods to four or five times their normal value is costing the government a lot of money.

Leakages of various types are substantial enough to cause serious difficulties in the management of the day-to-day running of government affairs. The country is cash-strapped ministries and departments are not able to access the money they need to function effectively.

On compliance

What are the consequences of ignoring the rules and regulations set out in the law? Are government ministries supportive of your work? To what extent is a lack of capacity at ministry and local government levels an impediment to proper audit practices in Sierra Leone?

Insufficient pressure is put on auditees to respond to the recommendations of reports. If there were greater consequences for ignoring these, perhaps attitudes would change. One solution would be to not release financial allocations to ministries until they enacted at least some of the recommendations from the ASSL audit. Ministries need to be incentivised to do the right thing if compliance is to become the norm. They do support us in allowing our auditors to carry out reviews, but when it comes to action on recommendations little changes.

The need for adherence to the law is not something that you need to go to a special school to learn. Nonetheless, it will not happen until there are consequences for flouting the rules, both for individuals and ministries. Until we get to that point, commitment to proper audit practices will continue to be a personal choice.

If malpractice is done totally off the books and we cannot see it, then we cannot talk about it. Rumour and speculation cannot be allowed to impinge on the auditing process. One way of addressing this problem would be to carry out a forensic audit, but we do not yet have the requisite skills or capacity.

I look forward to a scenario when, after Parliament has finished with our annual report, efforts are made to prosecute based on malpractice highlighted by our findings. In five years my office has never received a communication from the attorney general’s office about action being taken against public officials because of what we have uncovered. We have actively sought to engage both with our work, as they are the ones mandated to investigate those who have transgressed. The will to act has to come primarily from these institutions.

On the response to Ebola

The real-time Ebola audit conducted by the ASSL has been praised for highlighting concerns about how government funds were spent. You found that 30% of the funds allocated to dealing with the crisis were either not spent or not issued in accordance with the law. What did you learn from this audit? Has the government acted on its findings?

The major lesson, in hindsight, is that we should have gone in earlier. It was a difficult decision to know whether we should go in, because of the nature of the crisis. What were people going to think if auditors came in and started asking questions rather than helping? People were dying.

But when we started learning that concerns were being raised about the effectiveness of the response, we decided to act. In simple terms, a real-time audit involves monitoring expenditure and financial processes as and when the activities are taking place. It not only saves the government a lot of money but can quickly stop malpractice before it spirals out of control.

For serious breaches of financial management procedure I would support forcing the individuals responsible to pay back the money. It would send a strong message. But currently this does not happen. People continue to get away with transgressions.

On monitoring aid and investment

Is international donor funding in health, education and infrastructure and large-scale investment projects sufficiently open to scrutiny from the ASSL? Why is this important?

During the Ebola outbreak none of the funds that came in, apart from those that went directly to the government, were subject to the scrutiny of the audit office. When international partners claim they have helped improve the country in key sectors like health and education we would like to be able to verify and validate those claims. This could be done if auditing of these funds was standard practice. At the very least international actors could give us copies of their audits to put in our own reports. More broadly, we do audit World Bank-funded projects and conduct quality assurance on audits done for African Development Bank-funded projects.

We would like to engage in monitoring some of the infrastructure projects being undertaken in Sierra Leone; and also to carry out IT and extractive industry audits. We cannot do everything, however, and it would be difficult, for example, to obtain the contracts and documentation necessary to carry out an audit of Chinese infrastructure projects. We are not shying away from that challenge or any other, but it is important that we do not overstretch ourselves.

On transparency and public engagement

How does the work of the ASSL contribute to improving the awareness of citizens about government initiatives and projects that aim to deliver basic public services for citizens of Sierra Leone? What else could be done to improve engagement with the wider population?

In 2010 our annual report became a public document but it was not until 2012 that it became public knowledge. Take the South African municipal elections in August 2016 as an example. I watched a political rally the weekend before the vote where people were using the findings of the auditor general’s report to hold the municipal authority to account, asking questions about its misuse of funds. It is a great example of how the work of audit offices can push for change even when governments are reluctant to do so.

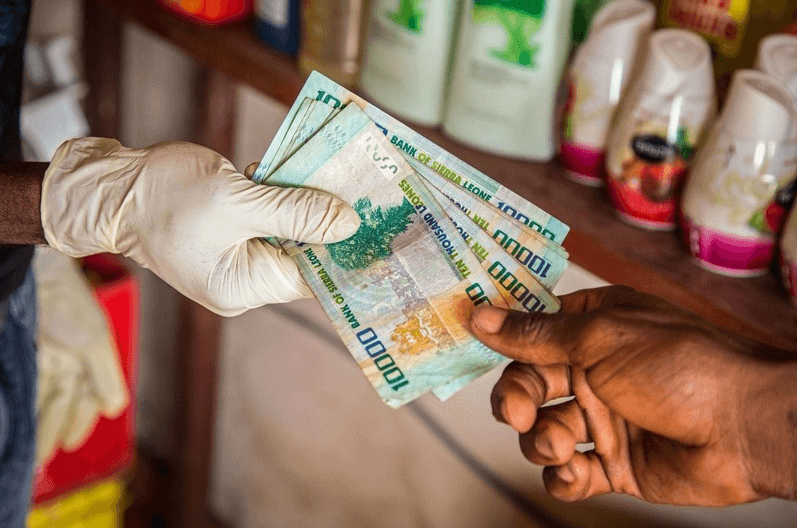

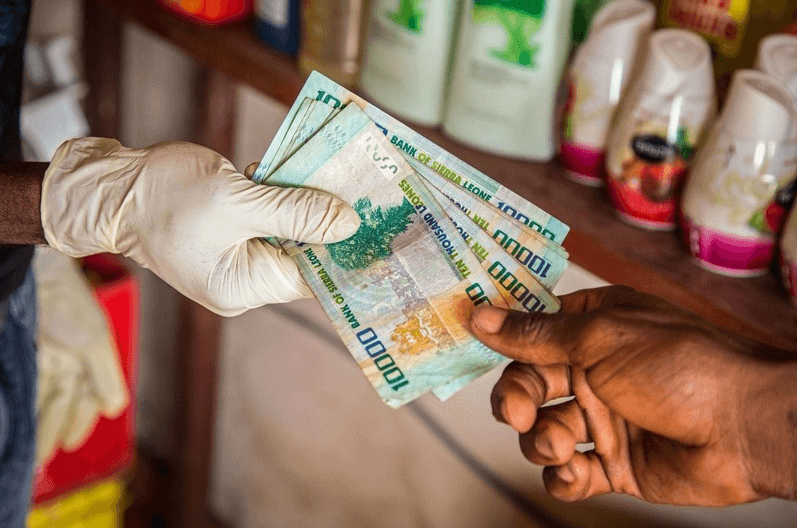

Photo: Africa Research Institute