WATHI propose une sélection de documents sur le contexte économique, social et politique en Sierra Leone. Chaque document est présenté sous forme d’extraits qui peuvent faire l’objet de légères modifications. Les notes de bas ou de fin de page ne sont pas reprises dans les versions de WATHI. Nous vous invitons à consulter les documents originaux pour toute citation et tout travail de recherche.

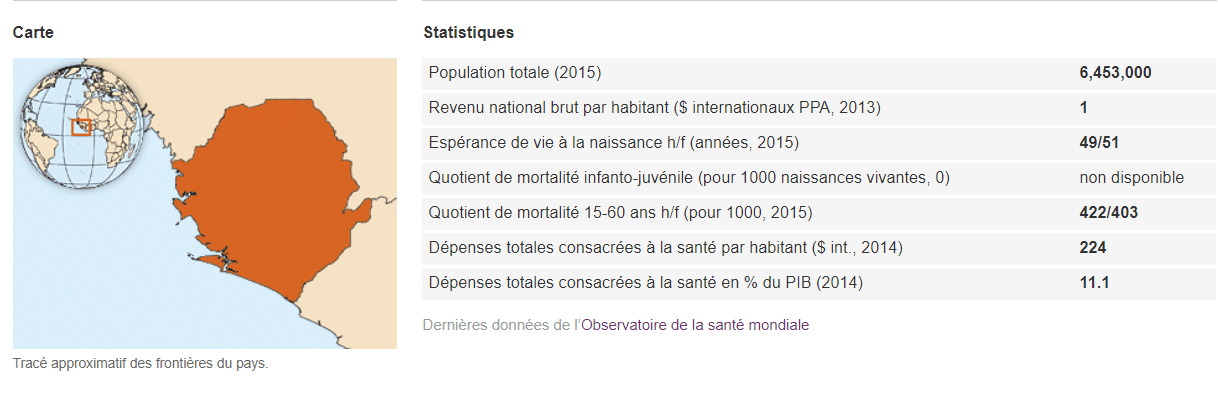

Source OMS

Source OMS

Fin de la résurgence de la maladie à virus Ebola en Sierra Leone

Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS)

L’Organisation mondiale de la Santé se joint au gouvernement de Sierra Leone pour marquer la fin de la récente résurgence de la maladie à virus Ebola dans le pays. À ce jour, le 17 mars, 42 jours – soit deux cycles d’incubation du virus – se sont écoulés depuis que la dernière personne confirmée comme atteinte par la maladie dans le pays a donné pour la deuxième fois un résultat négatif au dépistage du virus. Cette dernière résurgence d’Ebola porte à 3590 le nombre de vies emportées par une épidémie qui a dévasté familles et communautés à travers le pays et bouleversé chaque aspect de la vie.

Ce jour représente une étape importante dans l’effort du pays pour gagner la bataille contre Ebola. L’OMS loue le gouvernement de Sierra Leone, ses partenaires et la population pour la réponse efficace et rapide opposée à cette dernière flambée. Depuis le personnel infirmier, les vaccinateurs et les mobilisateurs sociaux jusqu’aux personnes chargées de retrouver les contacts, aux conseillers et aux dirigeants communautaires, les habitants des districts touchés se sont mobilisés sans tarder et leur implication et leur dévouement ont eu un rôle et un impact déterminants.

Le confinement rapide de la résurgence a aussi constitué une démonstration en temps réel de la capacité accrue au niveau du pays, du district et des communautés, à répondre aux flambées de maladie à virus Ebola et autres urgences sanitaires et à atténuer leur impact. Les investissements consentis dans les équipes d’intervention rapide, la surveillance, les moyens de diagnostic en laboratoire, la communication à propos des risques, les mesures de lutte contre l’infection et d’autres programmes ont été mis à l’épreuve et ont clairement porté leurs fruits.

Néanmoins, l’OMS continue de souligner que la Sierra Leone, comme le Libéria et la Guinée, sont encore exposés à un risque de résurgence de la maladie à virus Ebola, en raison, pour une grande part, de la persistance du virus chez certains survivants, et doivent donc restés à un stade avancé d’alerte et prêts à la riposte.

Il faut maintenir des moyens solides de surveillance et de réponse aux situations d’urgence et, en parallèle, des pratiques d’hygiène rigoureuses dans les foyers et les établissements de soins ainsi qu’une participation active des communautés. Des soins, des tests de dépistage et des conseils doivent aussi être proposés aux survivants dans le cadre de services de santé améliorés s’adressant à tous.

L’OMS continue de collaborer avec le gouvernement de Sierra Leone et ses partenaires pour mettre sur pied un système de santé plus résilient, capable de prévenir et de détecter les futures flambées et d’y répondre, et pour redynamiser et renforcer les services de santé essentiels à travers le pays.

Urban Health country profile

World Health Organization

Corruption in healthcare in Sierra Leone is a taboo – but it does exist

CTV cameras scan the triage area, as women in brightly coloured fabric line up with their children. A painting on the wall shows a lady with a baby strapped on her back under the sign “yu nor de pay no money”. At the children’s clinic where I work, healthcare is free. This is something that is not taken for granted here. In Sierra Leone, as in many parts of the world, healthcare often comes with a catch.

Corruption in healthcare is a taboo subject, with both patients and staff often reluctant to admit its existence. But it does exist. And it extends from mismanagement at high levels of government to bribes and unauthorised charges for frontline services. It is widespread and under-reported and can have devastating consequences.

Sierra Leone in West Africa was at the epicentre of the recent Ebola crisis. A 2015 Transparency International survey reported an astonishing 84% of Sierra Leoneans had paid a bribe for government services. There is huge systemic corruption, up to a third of money given to fight Ebola remains unaccounted for. An internal government audit showed £11m was missing from the first six months of the outbreak alone. Despite having rich natural resources, the majority of the population live in grinding poverty. The country has one of the highest rates of maternal and infant mortality in the world with 1,360 mothers dying per 100,000 live births.

It was in an effort to tackle this horrifying statistic that the president, Ernest Bai Koroma, introduced the Free Health Care Initiative in 2010, specifically granting free care for under-fives and pregnant and lactating mothers. This was a bold and much needed move for which he should be applauded. However, in spite of this campaign there are widespread reports of charges for frontline services. A 2016 report by the Campaign for Human Rights and Development International describes “rampant bribery” throughout the healthcare system in Freetown.

There are stories of women being told that their babies will not be monitored in labour unless they give money to the nurse in charge, unofficial payments being taken in order to triage or register patients and medications and medical equipment that should be free, being sold at a mark-up. Sierra Leone has an adult literacy rate of 40%. Many people are not empowered to stand up for their right to free healthcare, and are often not even aware that the charges they are being asked to pay are unauthorised. There is inevitably a fear of reporting corruption as people are afraid they may be victimised or excluded altogether next time they come.

But the government is trying to make changes to that culture. At the state run hospital in the centre of town there are now posters which proclaim “pay no bribe”, urging people to report any cases of bribery they may encounter. This new initiative organised by Sierra Leone’s Anti-Corruption Commission, and funded by the UK Department for International Development, allows people to call a toll-free number to report cases of corruption across the education, electricity, health, police, water and sanitation sectors. This innovation goes some way to putting some of the power back into the hands of the people using these services. In the last quarter of 2016, 23.2% of bribes reported on these hotlines were paid to healthcare officials…

Sierra Leone country profile

Universal Health Coverage Partnership

Sierra Leone is a West African country with a population of 6 million people and a life expectancy at birth of 45 years (male) and 46 years (female). A debilitating 11-year-long civil war ended in 2002, leaving the country’s infrastructure and health system in tatters. Following years of slow progress, the government announced the Free Health Care Initiative in 2010. In 2014, Sierra Leone was one of the three countries most affected by the Ebola virus outbreak, with a total number of 3,799 reported deaths (WHO, March 2015). The country is still working towards putting a definite end to the epidemic (zero cases), as well as tackling its socio-economic impact. Accordingly, the EU-WHO Partnership roadmap’s initial focus is under review to take account of WHO’s ongoing support to the Ministry of Health for the elaboration and the integration of a medium-term Ebola recovery plan into the national health policy framework…

Where Do People Go When They’re Sick?

Traditional healers versus modern clinics in Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone’s health system has a lot of problems—it’s underfunded, understaffed, and underequipped. It’s now facing what could be the largest crisis in its history if the Ebola outbreak rages out of control. But the health care system also poses a challenge because of the way it is set up. It’s a prime example of what’s called a plural health system, made up of multiple service providers, from government clinics and hospitals to traditional healers and birth attendants to community health workers and peer support groups.

Plural health systems tend not to function in straightforward ways. Sometimes providers coordinate with one another, at other times they compete. Some are perceived as trusted and legitimate local institutions, while others may be viewed with great suspicion. And these things vary considerably from place to place.

New research we just published for the Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium illustrates how plural health systems in Sierra Leone work. It shows how local communities navigate the health choices available to them—who does a mother turn to when her kid gets sick?—and explains some of the factors driving people’s health-seeking preferences. Why is it, for example, that a family continues to call on the local traditional healer when their community has a relatively sophisticated government-run health clinic?

One factor that comes out particularly strongly is the power of relationships. In some communities we visited, people were extremely hesitant to use the government’s local health clinic. Some people complained of clinic staff being rude and unhelpful or denying women water after a long walk to the clinic. Others explained how clinic staff “look down upon you” if one’s physical appearance suggests a lack of money. On the other hand, traditional healers who have been operating for years and are deeply embedded within the social fabric of communities have often accumulated considerable trust among local people. Although their dynamics differ from place to place, it is social relationships such as these that end up pushing health care seekers towards certain providers and away from others—even if that is not the best outcome for public health.

Our research, and other work like it, suggests policymakers should assess health systems from the perspective of the people who actually use the services. This is as important for long-term efforts to prevent public health challenges like undernutrition as it is for attempts to contain outbreaks of deadly viruses such as Ebola.

Mental health – the silent crisis in Sierra Leone

Today, thousands of people with mental health conditions around the world are deprived of their basic human rights. They are not only discriminated against, stigmatized and marginalized, but are also subjected to emotional and physical abuse in institutions and in the community.

Poor mental health care, due to a lack of qualified health professionals and dilapidated facilities, promote further violations. In some countries, World Mental Health Day is observed as part of the wider mental illness awareness week. The reality is that financial and human resources allocated for tackling mental health issues are inadequate, especially in low resource countries like Sierra Leone. The majority of low and middle-income countries spend less than two percent of their health budget on mental health.

Many countries have less than one mental health specialist for every one million people in the country. And to compound this problem, a considerable proportion of the limited resources are never spent on mental hospitals, but rather on services delivered through community and primary health care.

Countries need to increase their investment on mental health, as well as shift available resources towards more effective and patient-centered services. Sierra Leone has very few mental health workers, a single psychiatrist, two psychiatric nurses, and a handful of social workers and counsellors. There is therefore a desperate need for more mental health workers in Sierra Leone. But the situation in Sierra Leone is exacerbated by the fact that it is extremely difficult to recruit students into psychiatry, which is frowned upon and stigmatised in all African countries.

With a decade of one of the most brutal civil wars the world has ever seen and an Ebola outbreak, Sierra Leone is facing an unprecedented mental health crisis, with thousands of trauma cases across the country. Dr. Edward Nahim, Sierra Leone’s only psychiatrist, speaking in an exclusive interview, explained that the civil conflict and the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone have resulted in serious psychological problems such as post traumatic stress disorder, psychosis and depression.

These conditions he said might also lead to an increase in lawlessness, drug abuse, poverty, discrimination, and further stigmatization. He noted that mental Health remains a major public health concern in Sierra Leone, and called for appropriate needs and resource assessment to be conducted as a starting point in tackling this crisis. The consultant psychiatrist said the main goal is to have relevant data in place that will inform future planning and delivery of a comprehensive mental health service.

“Mental health problems fall into two main categories with a certain overlap. The first category includes traditional mental health problems seen in any country, rich or poor and in peace or conflict. “The second group includes special problems related to conflict, post conflict context with exposure to potentially traumatic events and lack of protective factors to contain these events, due to severe social distress caused by poverty, general hardship, bad nutrition and physical health problems,” he added.

Dr. Nahim says that based on a joint Ministry of Health and Sanitation and WHO survey in Sierra Leone, “more than 700,000 people are with severe mental health problems needing medical treatment; more than 350,000 psychotic patients induced by drugs and alcohol abuse, as well as by severe infections like cerebral malaria; more than 20,000 with a severe Bipolar manic depressive disorders; more than 175,000 are mentally retarded; and more than 175,000 epileptics and schizophrenics.”

Sierra Leone with an estimated population of more than six million or more has people with psychosis (2%); depression (4%); substance misuse disorder (4%); learning disabilities (1%) and epilepsy (1%). In a brief chat, a mental health patient, who prefers anonymity, said this about some of the social problems in post war Sierra Leone and that of the Ebola outbreak: “The dignity of many people with mental health conditions is not respected. People with mental health conditions in Sierra Leone and the world in particular experience stigma, discrimination and wide-ranging violations which strips them of their dignity.”

This mental health patient, who has recovered from the illness, further said that many people suffering from mental illness are subjected to physical, sexual and emotional abuse, and neglect in hospitals and prisons, but also in the communities. “This is a serious problem, because they need the support of psychiatrists to help combat some of the social problems which emanated from trauma of war and the Ebola outbreak in the country”, he concluded. A father, whose son is suffering from a mental health condition, says that any person with mental health problem in Sierra Leone faces high level of stigma and discrimination. “They are tagged as having mental health problem; they experience social deprivation; losing their jobs; losing social prestige and becoming isolated from their families and society,” he said…

Sierra Leone: Politicians urged to prioritise healthcare

Politicosl.com, Kemo Cham

Out of every five children in Sierra Leone, one is likely to die before celebrating their fifth birthday, according to a UNICEF report. This reality is at the center of the phenomenon known as infant mortality, one of the major health conundrums confronting Sierra Leone which is ranked among the top five countries globally with the highest rates of Infant Mortality at 114 deaths per every 1000 live births.

Infant mortality is actually just one side of a twin health problem for Sierra Leone; the other half is maternal mortality – that’s the number of women dying due to pregnancy related causes. Sierra Leone tops world ranking in this, with 1, 165 deaths per every 100, 000 live births.Teenage pregnancy, Malnutrition, and Immunization have been identified as the three major factors fueling maternal and infant mortality in Sierra Leone. Experts say addressing these issues requires a responsive health system, which calls for a collaborative effort among healthcare providers and politicians. A coalition of NGOs and civil society organisations, headed by Save the Children International, last month initiated a campaign designed to mobilize political support in this regard.

Ahead of the March 7 general elections, political parties are putting together their manifestos. The healthcare campaigners want these health issues prominently captured in these development blueprints. Political parties should not just draw programs that make people vote for them, but ones that will improve the lives of the people, especially women, said Zainab Moseray, Registrar of the Political Parties Registration Commission, at one of two consultative sessions held with political parties representatives. The first session brought together lawmakers and technical experts in the areas of concern.

All 14 political parties registered and certified by the National Electoral Commission at the time were invited to the second session which was hosted at the Family Kingdom Resort in Aberdeen, Freetown. The campaigners say political will is crucial in ensuring a sound healthcare system not just to guarantee adequate funding, but also to formulate relevant policies and lead efforts of social mobilization.

“The idea is to challenge political leaders to come out and commit themselves to making difference in the lives of women and children,” said Mohamed Bailor Jalloh, Chief Executive Officer Focus 1000, a leading local partner in the initiative. Teenage pregnancy is rife in Sierra Leone, fueled by numerous cultural and traditional factors, including poverty and early marriage which is driven by religious considerations. In some communities girls as young as 12, are forced into marriage. At such age, say reproductive health experts, their bodies are highly susceptible to a lot of life threatening post-partum complications.

According to the last Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), 46 percent of all adolescent deaths in Sierra Leone were linked to maternal deaths. Babies born to teen mothers also tend to have low birth weight and are predisposed to a variety of illnesses. According to the National Nutrition Survey of 2014, one in 3 under-five children in Sierra Leone is malnourished. This translates to nearly half a million children. Experts say malnutrition exposes both mothers and their babies to a horde of diseases which, if not handled in time, can lead to untimely death.

The NGOs behind this initiative are all members of the SUN [Scalling Up Nutrition] Movement, a global campaigned against malnutrition. In Sierra Leone, the Secretariat of the Movement is hosted in the Office of the country’s Vice President. Nutrition expert Dr Mohamed Foh coordinates the Secretariat. He said hosting of the Secretariat at this level is enough demonstration of political will on the part of government, stressing the need for further collaboration with the private sector.

Dr Foh said to reduce either child or maternal mortality requires investment in nutrition, noting that with adequate nutrition, immunity against diseases is boosted. “A child who is stunted is a child with cognitive challenges and can hardly attain their full potential,” he said. He added: “A public private partnership is also required because we need research, we need to produce our own, we need to feed our own people. And we need to encourage the businesses.” Nearly half of Sierra Leone’s population – 3.5 million people – faces hunger, according to the Global Hunger Index. To overturn this situation requires policies that increase allocations to relevant ministries geared towards increasing annual food production.

Specific interventions

Malaria, pneumonia and diarrhea have been identified among the three main killer diseases of children in Sierra Leone. Experts say these are less likely to kill if a child is well nourished and most likely to kill if under nourished. Exclusive breastfeeding is one way of addressing the issue of malnutrition in children and which require public private partnership. For instance, efforts are already underway through the SUN Movement to halt the proliferation of breast milk substitutes which campaigners say have encouraged many mothers not to breastfeed their babies.

National health promotion strategy of Sierra Leone (2017–2021)

Government of Sierra Leone, Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Health Education Division

Key Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Data

While behavioural data is still limited, the following key health issues are considered priorities by the government and partners. Additional health areas being addressed are included in Appendix A.Additional Health Landscape in Sierra Leone. Maternal, Neonatal and Under Five Mortality While major improvements have been seen over the years in these areas, Sierra Leone still has one of the highest rates of maternal and neonatal mortalities. In 2015, WHO (World Health Organization) estimated the maternal mortality ratio to be 1,360 deaths per 100,000 live births.

Hemorrhaging or heavy bleeding causes an estimated one-third of maternal deaths; another 11percentare related to malaria or anemia caused by malaria. Nationwide, 6percentof women die while pregnant, in delivery or after birth (DHS- Demographic and Health Surveys- 2013). While these conditions are treatable, infrastructure and financial barriers frequently keep women from attending a facility for delivery and from receiving necessary services and medicine for prevention.

During the Ebola outbreak, fears of catching the disease contributed to keeping women away from facilities providing maternal health care, including deliveries. As a result, according to a Voluntary Services Overseas (VSO) study, maternal deaths increased by 30 percent during the outbreak (VSO, 2015). Along with high rates of maternal mortality, the infant and child mortality rates in Sierra Leone are also among the highest in the world. While the infant mortality rate has decreased significantly in the past decade, of 1,000 live births there are an estimated 35 deaths within the first month of life (WHO, 2015) and an estimated 92 deaths before the infant reaches one year (DHS, 2013). Unfortunately, during the Ebola epidemic newborn deaths increased by 24 percent, largely due to a decline in facility deliveries (VSO- Voluntary Services Overseas- 2015).The under-five mortality rate varies by source but was estimated at 156 deaths per 1,000 live births (DHS, 2013).

Most cases of infant and child death are preventable, with the majority being attributed to malaria, diarrhea and pneumonia. For example, 55 percent of under-fives do not sleep under an ITN (MIS, 2013), 3 percent of children with diarrhea did not receive any treatment (DHS, 2013), and 15 percent of children are not treated with oral rehydration salts (ORS) (DHS, 2013). According to the WHO (2015), 41 percent of deaths of children under five are due to malaria.

Reproductive Health, Family Planning and Teenage Pregnancy

Within the country, there is almost universal knowledge of at least one modern contraceptive method. One-quarter of women have an unmet need for family planning, with 17percentdesiring to space future births and 8percentdesiring to limit births (DHS, 2013). While precise numbers are not known, this unmet need likely increased during the Ebola outbreak.

The 2013 DHS revealed that 28 percent of adolescents (aged 15 to19) have begun childbearing and teenage pregnancies account for more than one third of all pregnancies in the country. Over half of all women have become mothers by age 20 (DHS, 2013). In addition to the non-fatal complications that younger women are more susceptible to in pregnancy and delivery, teenagers in Sierra Leone also are at the highest risk of maternal mortality of any age group, with 40 percent of maternal deaths occurring with teenage girls (MICS – Malaria Indicator Survey- 2010).The high rates of teenage pregnancy are closely related to the prevalence of early marriage, as early marriage is seen as a protection mechanism for girls against involvement in extra-marital sex (Coinco, 2010). Further, 31 percent of adolescents reported having sex before the age of 15 (MoHS, 2016).

Reducing teenage pregnancy is one of the government’s key health priorities. Many reports have indicated an increase in unplanned pregnancies – particularly among teenagers and a decrease in uptake of family planning services during the Ebola epidemic.

Objective 1: Strengthen health promotion structures

The Government of Sierra Leone has numerous structures with roles and responsibilities in health promotion. These structures are described in more detail in the Situation Analysis.5While many of these structures were active during the Ebola outbreak, where they played an essential coordinating role, many have since become dormant. Government and non-governmental partners alike are calling for the revitalization of those mechanisms, emphasizing the importance of building technical capacity to effectively manage and increase coordination among all health promotion structures. It is noteworthy that key health promotion partners, such as UNICEF and WHO, a real ready working with national- and local-level structures to clarify roles and increase effectiveness. These efforts will be a critical building block toward strengthening community ownership as part of the MOHS recovery plan.

Objective 2: Strengthen national health promotion interventions

One of the benefits of creating a national strategy for health promotion is that it can add value to the work of individual actors and agencies “areas for common action,” validated represent opportunities to increase national program

- Models for implementation

- Intended audiences for our

- Key change agents

- Typical health promotion interventions

- Key behavioural determinants

- Collaboration with all technical units of the Ministry on their priorities for health promotion

- A national umbrella campaign

- An emergency communication plan

- A multisectoral response

Objective 3: Improve human resources and capacity strengthening for health promotion

The constraints on human resources for health promotion in Sierra Leone are a major barrier to the implementation of consistently high-quality programming at the scale that is required. While these constraints cannot be fully addressed in one five-year strategy, the MOHS can establish a foundation for health promotion human resources – including for logistical support – on which future programmes can build. Broadly, approaches in this area will fall into two categories of action: training and workforce policy.

Objective 4: Raise awareness and mobilize resources for strengthened health promotion

To shift the norm away from being the “spare tyre” in the health system, the HED will develop a series of advocacy activities so that new and higher expectations of the HED and health promotion activities can take root. Ultimately, the aim will be to create opportunities to influence key public and private sector decision-makers to increase resources to support the HED and health promotion interventions. A number of implementing partners have a strong experience in advocacy – such as Health for All, Save the Children, Mama Ye, World Vision and Inter-Religious Council – and will, along with other partners, be called on to support the HED to achieve this objective.

Objective 5: Improve monitoring and evaluation systems for health promotion

M&E (Monitoring and Evaluation) allows for an in-depth understanding of the impact that health communication initiatives have on people’s attitudes, behaviours and other psychosocial factors, which ultimately affect health outcomes. Having a solid evidence base on health promotion activities in the country will not only inform the MOHS (Ministry of Health and Sanitation) and partners of what approaches and messages are working and which are not, but will also build a case for the importance of health promotion to overall national health priorities.

A priority of this objective will be to develop a standard M&E framework for both the management and implementation of health promotion activities. This framework will be used at the national, district and community levels. For example, data collection will be standardized to allow for monitoring of inputs, outputs and the reach of health promotion activities, considering elements such as the socio-demographic characteristics of people reached, audience reactions and feedback to health promotion interventions and positive trends in behaviour change, where possible.

Objective 6: Strengthen knowledge sharing and management

Functioning knowledge management systems are crucial to the success of this Strategy and the impact of national health promotion activities. It is essential that the HED has a strong documentation, filing and sharing system. Broadly speaking, beginning with the simplest and highest priority and continuing to the more complex later priorities, the following initiatives will be pursued over the life-span of this Strategy:

- Develop a functional library of health promotion materials and resources in a venue that is easily accessible to the widest array of programme partners

- Establish a consistent, long-term plan for meetings and events that can be used as opportunities for information exchange

- Create a health promotion newsletter to share information on tools, partners and programmes

- Establish standard, intuitive and consistently-applied electronic filing systems in directories accessible to a number of HED staff

Create a system of health-promotion-related listservs for members of the health promotion and communication pillars to share information with each other Given the relatively low access to internet connectivity, a priority for this Strategy will be to invest in improving internet access at the national and district level. In the meantime, face-to-face knowledge sharing systems are being emphasised. A functioning knowledge management system will share critical data, best practices, guidelines and other important documents to improve overall efficiency, coordination and leadership.

Where does a Sierra Leonean mother take her children when they get sick? There is more than one option.

Crédit photo: Slate.com