Author(s): Vivienne Walt

Affiliated Institution: Fortune

Type of Publication: Article

Publication Date: June 2014

Saturday night in Africa’s biggest city, Lagos, and five of us are lip-reading across the table above the thumping music at Rhapsody’s, a restaurant-club on upscale Victoria Island. Every few minutes a waiter parades past us holding aloft a see-through ice bucket, with sparklers ablaze and a bottle of Dom Pérignon Rosé Vintage, priced at 150,000 naira (around $924)–about one-third the average Nigerian’s yearly income. “You have to let people know you’re ordering it,” says my companion, laughing. When we finally stagger outside at midnight, the valet parkers are maneuvering SUVs out of spaces, carefully avoiding the beggars on the sidewalk.

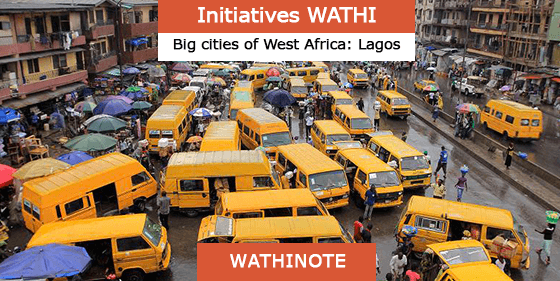

The disjuncture between the super-rich and dire poor is seen on almost every corner of this megalopolis of about 20 million. This spit of land on the Atlantic coast held just 2 million people in the 1970s. It’s now the region’s commercial powerhouse and one of the fastest-growing cities in the world. Thanks to an oil boom and an expanding economy that has made Lagos a draw for rural villagers hoping for a better life, a high birthrate the average Nigerian woman gives birth to more than five children and more and more returnees from the U.S. and London, the growth shows no signs of slowing. Every year about 600,000 people are added to Lagos, and the UN estimates that within a few years it could edge out Karachi to become the world’s third largest, after Tokyo and Mumbai.

Congested roads and high density hardly match the world’s vision of Africa as a place of mud-hut villages and sweeping landscapes. But increasingly this will be the real Africa. Within 20 years most Africans will live in urban areas. By 2050, Africa’s city dwellers will more than triple, from about 400 million to 1.2 billion one of the fastest urbanizations in human history, according to a report earlier this year by the UN-Habitat. Managing that growth is a challenge the likes of which the continent has never seen and yet Lagos offers a laboratory for Africa’s future. At stake is whether its exploding growth will widen Nigeria’s huge income gulf–about 60% of Nigerians live on less than $1.25 a day–or create more equitable ways of living.

Thanks to an oil boom and an expanding economy that has made Lagos a draw for rural villagers hoping for a better life, a high birthrate the average Nigerian woman gives birth to more than five children and more and more returnees from the U.S. and London, the growth shows no signs of slowing

It’s no surprise that the city is straining under the growth. Because of decades of ineffective government control, electricity is in critically short supply. Nigeria has finally opened investment to private power companies, but Lagos generates a minuscule 2,000 megawatts of electricity–less than half of what’s available for a single block in Midtown Manhattan–and every household and store depends on diesel generators.

Yet there are signs that Lagos is changing fast, offering hope for what’s possible in Africa’s lightning transformation. When Lagos’s visionary governor Babatunda Fashola took power in 2010, he enforced local tax collection–an unusual idea in Africa. That has brought Lagos billions, giving it both autonomy from the country’s corrupt government in Abuja, the capital, and new projects, like a planned rapid-transit network, a $50 billion infrastructure program that includes West Africa’s first suspension bridge, and two forthcoming power plants that will finally ease the electricity shortage and even light Lagos’s streets at night.

Fashola now markets his city as “Africa’s Big Apple.” And in fact, much like New York, Lagos has a multitude of thriving industries. In April, Nigeria became Africa’s biggest economy, displacing South Africa, in part driven by growth in Lagos, with its growing film (in Lagos it’s called Nollywood) and fashion industries. There are entrepreneurs, financiers, and energy CEOs whose worth is rocketing in value on Africa’s energy boom. Lagos is also the hub of Nigeria’s banking activity, and it has retail and manufacturing operations as well. Earlier this year Nissan began rolling out Lagos-made SUVs. Lagos’s rich set is increasingly visible. Shoreline CEO Karim, to name one, keeps 36 thoroughbred Argentine horses at the Lagos Polo Club, where he entertains the city’s movers and shakers–many of them, like him, back home after years living in Los Angeles, Washington, London, and elsewhere.

Congested roads and high density hardly match the world’s vision of Africa as a place of mud-hut villages and sweeping landscapes. But increasingly this will be the real Africa. Within 20 years most Africans will live in urban areas

If you cross the bridge from the Polo Club, you reach the dirt-poor neighborhood of Makoko on the mainland’s Lagos Lagoon. There, more than 100,000 people live in rickety dwellings on stilts that teeter over the fetid lagoon. Our canoe snakes through the sewage-filled canals until we arrive at a three-story, A-frame structure: a schoolhouse that floats atop 265 recycled-plastic drums, designed by Kunle Adeyemi, a Nigerian architect who moved back in 2011 after working in Rotterdam with the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas and started his own Lagos firm, Nlé. The school, built for 60 students, was made to withstand floods, since it can rise with the water level. “I’m very worried about what Lagos will look like in the next decades,” Adeyemi says. “You see Lagos from the air, and it’s a sprawl with no infrastructure.” Up close, however, Lagos is much more than that. With its exploding population, plusses and minuses, and potential, it is also Africa’s future.

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.