Author (s): Tolu Ogunlesi

Affiliated Institution: The Guardian

Type of Publication: Article

Date of Publication: 24 August 2015

The Nigerian city is an enigma, ranking near the bottom of the least liveable places. So why is it near the top in a happiness survey? I think I know.

One day, in February last year, the road that leads to my house in Lagos was removed. Without prior warning or explanation, a group of labourers began pulling out recently laid paving stones. By the end of the week the road was completely bare, the stones piled high to one side. The story my neighbours and I later heard was that the private developer who had laid the stones months earlier, having lost out on a soon-to-be-signed property deal, decided there was no point leaving his road for others to enjoy.

Rather than express shock or dismay, I tweeted about the event, in the tone of one daring anyone to trump it with a cooler story. That’s how many of us who live in Lagos view the city. We wear its many dysfunctions as a badge of honour, proudly swapping real-life stories that elsewhere in the world would belong in the realms of sci-fi or satire.

The abundance of these stories is the reason why the canonisation of Lagos as one of the world’s least liveable cities no longer raises many eyebrows. In this year’s liveability index, produced by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), we popped up fourth from the bottom, somewhere between Tripoli and Damascus which were both sent to the bottom by the conflicts that have ravaged them in recent years.

The EIU explains how its ranking is drawn up: “Every city is assigned a rating of relative comfort for over 30 qualitative and quantitative factors across five broad categories: stability; healthcare; culture and environment; education; and infrastructure. Each factor in a city is rated as acceptable, tolerable, uncomfortable, undesirable or intolerable,” and this is informed by the opinions of “in-house analysts”, “in-city contributors”, as well as hard data.

We wear its many dysfunctions as a badge of honour, proudly swapping real-life stories that elsewhere in the world would belong in the realms of sci-fi or satire

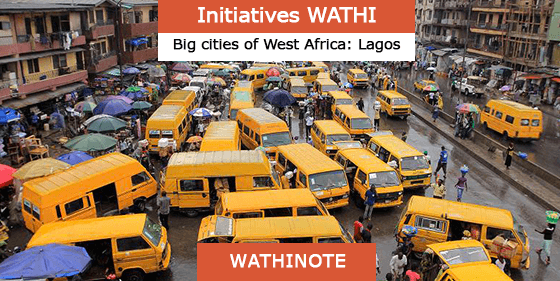

Based on that criteria, it’s easy to see why Lagos would fail on every score. Take infrastructure: roads, public transport, housing, electricity, water, telecommunications. Lagos is the only city of its size in the world that doesn’t have a city-wide rail system. That’s 15 to 21 million people (no one knows exactly how many) who are forced to commute by road. Imagine London without the tube but with twice the population – the perfect setting for a dystopian novel.

The provision of utilities has not kept pace with the growing population. In the part of town where I live there doesn’t seem to be a public water system; everyone depends on boreholes. On the “environment” category of the index, which measures things like temperature, here too Lagos fails. Even if the city had pavements (it doesn’t), flaneurs would still find it unappealing on account of the heat and humidity.

Yet, for all its dysfunction, Lagos remains a remarkable city, and it would be unfair and inaccurate to view it only in terms of a score in a “liveability” study. What we lack in infrastructure, we make up for in infectious optimism and energy.

Yes, life here is not ideal; the city could and should be a vastly more liveable place. But those of us who live in Lagos have simply learned to make the most of the status quo. And we’re grateful that technology and increasing political and civic awareness are throwing up unprecedented opportunities for young people to play a part in making our city better. From urban waste management solutions to traffic monitoring apps to public finance transparency initiatives, young Lagosians are working against the odds to bring their city in line with global standards. It’s our zeal to make life better that makes Lagos liveable. Could you say that about where you live?

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.