Author: David Pilling

Affiliated Institution : Financial Times

Type of publication : Article

Publication Date : March 25, 2018

In a country that is a byword for poor governance, Lagos is thriving — attracting investment and private enterprise. So what can the rest of Nigeria learn from it? Just to the east of Lagos, in the rapidly expanding new city of Lekki, a huge industrial project is taking shape. The Dangote oil refinery, with a capacity of 650,000 barrels a day, will cost at least $12bn to complete and be the biggest refinery of its type in the world.

If all goes to plan, when the refinery enters production in the first quarter of 2020, it will address many of the structural problems that have cursed Nigeria since it discovered huge quantities of oil 50 years ago. Because the country exports crude and imports refined products that are subsidized by the state, a plethora of dealers and middlemen has sprung up to make easy fortunes out of the arbitrage opportunities.

That it has taken a Lagos-based businessman and not an Abuja-based politician to tackle so fundamental an issue says much about what is wrong with Africa’s biggest economy. Yet it could also hint at what is going right. Mr Dangote is a symbol of what private enterprise can achieve if it is provided with the right incentives. Though a northerner by birth, he also represents a real Nigerian success story: Lagos.

Since the federal government moved to Abuja in 1991, Nigeria’s former capital and commercial hub of roughly 20m people has taken off. Starting in 1999, with the election of Bola Tinubu, a former Mobil Oil executive, Lagos has had three administrations that have harnessed the private sector to turn the city into the most productive and dynamic part of Nigeria’s economy. It was by offering Mr Dangote tax incentives in the Lekki free trade zone that the state persuaded him to build his refinery in Lagos.

Lagos state output in 2017 was $136bn, according to official estimates, more than a third of Nigeria’s gross domestic product. The city is the centre of most of the country’s manufacturing and home to a pan-African banking industry as well as a thriving music, fashion and film scene that reverberates around the continent. More recently, it has become a tech hub to rival Nairobi’s so-called Silicon Savannah.

That it has taken a Lagos-based businessman and not an Abuja-based politician to tackle so fundamental an issue says much about what is wrong with Africa’s biggest economy. Yet it could also hint at what is going right

The Lagos economy is significantly bigger than that of the whole of Kenya, east Africa’s most dynamic country, with a nominal per capita income of more than $5,000, more than double the Nigerian average. The population, just 1.4m in 1970, has nearly doubled from 11m a decade ago as thousands of people arrive each day to seek a better life.

The relative success of Lagos, a city as dynamic as many of the booming cities of Asia, has mostly been lost in the less uplifting story of Nigeria. The potential economic powerhouse of the continent, the country has all the ingredients for success. A huge population gives it the scale other African economies lack. It is a coastal trading hub and the world’s sixth-biggest oil exporter.

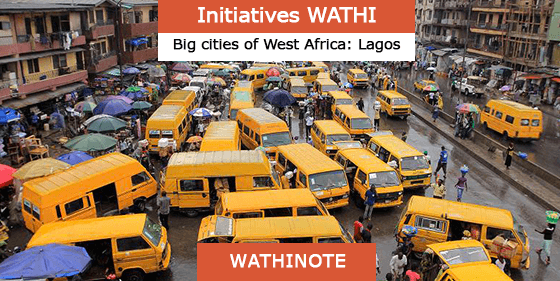

Toni Kan, a writer and entrepreneur who styles himself as “the Mayor of Lagos”, agrees his adopted hometown has made huge strides. The paved road network, including some world-class toll roads, has expanded significantly, he says, and the city’s once notorious gridlock has eased, although critics complain the biggest improvements have come in wealthy neighbourhoods. Old yellow buses have been phased out and a more integrated transit system adopted.

Culturally, says Mr Kan, Lagos is unrecognisable from even a decade ago. Restaurants and music clubs are flourishing. Artists and musicians perform in thriving public spaces such as Freedom Park. A city once considered dangerous is now among the safest in Nigeria. Successive administrations belonging to the same All Progressives Congress party have installed more street lights and beautified the city. “I won’t say it’s gentrified,” says Mr Kan of a conurbation that was once a byword for dysfunction. “But you get the sense of a modern city.”

The Lagos economy is significantly bigger than that of the whole of Kenya, east Africa’s most dynamic country, with a nominal per capita income of more than $5,000, more than double the Nigerian average

Mr Ambode, the governor, estimates that, by 2040, Lagos will be the world’s third-largest urban conurbation after Tokyo and Delhi, with 30m people. The city has expanded physically, and is now shifting to an east-west axis in contrast to its traditional orientation from north to south. But it will struggle to accommodate the influx.

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.